By Guillaume Allègre, @g_allegre

To Bernard Maris, who nurtured debate on economics with his talent and his tolerance

You have reasons for not liking economists. This is what Marion Fourcade, Etienne Ollion and Yann Algan explain in an excellent study, The Superiority of Economists, with the main conclusions summarized in a blog post: ”You don’t like economists? You’re not alone!” Although the study mainly concerns the United States, it is also applicable to Europe. It presents an unflattering portrait of economists, and in particular elite economists: they have a strong sense of superiority, are isolated from other social sciences, and are comforted by their dominant position of economics imperialism. The study also shows that the discipline is very hierarchical (some economics departments are “prestigious” and others less so) and that internal controls are very strong (in particular because the vision of what constitutes quality research is much more homogeneous than in other disciplines). This has an impact on publications and on the hiring of economists: only those who have sought and/or been able to accommodate this “elitist” model will publish in the infamous top field journals, which will lead to them being recruited by the “prestigious” departments.

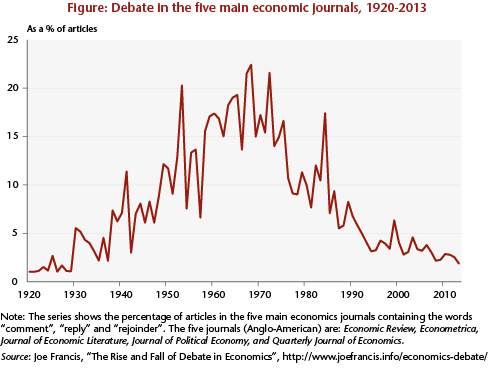

This would not be all that serious if the job of economists were not to make public policy recommendations. Furthermore, the “superiority” of economics is based largely on the fact that the discipline has developed tools to make quantitative evaluations of public policy. Economics is thus, in part, a science of government, while the other social sciences have adopted more critical postures towards established categories, structures and powers. The consequence of all this – the discipline’s hierarchies, the internal controls and the lack of appetite for critical positions – is that debate is now virtually banned in academic economics (another reason not to like economists?). The figure below shows that the number of articles written in response to another published article has dropped dramatically since the 1970s: while these then represented 20% of articles published in the five major academic journals, today they represent only 2%. Debate and criticism are virtually absent from the major journals, as are heterodox paradigms. These are relegated to the supposedly less prestigious journals, which does not lead to being hired into the top departments. However, there is also a strong sense in the discipline that debate and criticism must be engaged at the academic level, a level where criticisms are subject to peer review (with effects on selection, reputation, etc.). You have to be crazy and ask permission to publish a criticism, but no madmen are applying for permission, so no criticism is published. The Anglo-Saxons use the term Catch-22[1] to describe this type of situation.

If there is no longer any debate in academic journals, is it taking place elsewhere? In France, Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century seems to be the tree that is hiding the forest. The book’s success globally has pushed a number of people to take a position, but can we really speak of a debate in France and Europe? [2] In the face of Piketty’s success, Michel Husson (“Le capital au XXIe siècle. Richesse des données, pauvreté de la théorie” [Capital in the 21st Century – Wealth of data, poverty of theory]) and Robert Boyer (“Le capital au XXIe siècle. Note de lecture” [Capital in the 21st Century – Reading notes“]) have made some interesting criticisms based on, respectively, a Marxist and a regulationist approach. However, despite the quality of these critiques, it is apparent that this is not the focus of today’s debate: if the global or European tax on capital proposed by Piketty does not come into being, it will not be because Marxist and / or regulationist arguments have carried the day. It is rather arguments based on the tax incentives for growth and innovation that are more likely to convince the authorities. This line of argument is supported by Philippe Aghion, among others. With regard to the taxation of savings and wealth, and despite the similar partisanship of these two French economists (they both signed calls for Ségolène Royal in 2007 and then François Hollande in 2012), Aghion and Piketty and their co-authors do not agree on anything (which André Masson demonstrates in a forthcoming issue of the Revue de l’OFCE). Piketty proposes a highly progressive wealth tax and a new tax merging the CSG wealth tax and the income tax (IR), which would tax investment income, including capital gains, as well as labour income. Aghion proposes the exact opposite: he would rely more on VAT, avoid merging the IR and CSG taxes (a “bogus good idea”), and set up a “dual capital/labour system” with a “progressive tax on job income and a flat tax on income from productive capital”. It’s a good subject for debate, which will nevertheless not take place in the scientific journals, or elsewhere.

In fact, Piketty and Aghion are addressing the issue of the taxation of wealth from opposite angles: Aghion approaches it in terms of growth, while Piketty approaches it in terms of inequality. Why their models differ is understandable: they are not trying to explain the same phenomenon. Piketty’s concern is to explain changes in inequality, whereas Aghion is trying to explain changes in growth. Although they deal essentially with the same phenomena, the two approaches do not so much oppose each other as go off at right angles. Yet from the perspective of policy makers, a confrontation between the two is essential: otherwise how is it possible to choose between the different recommendations of Piketty and Aghion?

_____

Part of this post was published on the blog of Libération, L’économe :http://leconome.blogs.liberation.fr/leconome/2014/12/de-la-sup%C3%A9riorit%C3%A9-des-%C3%A9conomistes-dans-le-d%C3%A9bat-public.html

[1] The expression is taken from a novel by Joseph Heller with the same name. The novel takes place in wartime, and to be exempt from combat missions you have to be declared crazy. To be declared crazy, you have to apply. But according to Article 22 of the regulations, the very act of applying proves that the applicant isn’t crazy.

[2] In the United States, on the other hand, there was debate about the book. For example, Greg Mankiw (pdf), Auerbach and Hassett (pdf) and David Weil (pdf) all made recent critiques.