by Sabine Le Bayon, Mathieu Plane, Christine Rifflart and Raul Sampognaro

Since the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2008 and the sovereign debt crisis in 2010-2011, the euro zone countries have developed adjustment strategies aimed at restoring market confidence and putting their economies back on the path to growth. The countries hit hardest by the crisis are those that depended heavily on the financial markets and had very high current account deficits (Spain, Italy, but also Ireland, Portugal and Greece). Although the deficits have now been largely resolved, the euro zone is still wallowing in sluggish growth, with deflationary tendencies that could intensify if no changes are made. Without an adjustment in exchange rates, the adjustment is taking place through jobs and wages. The consequences of this devaluation through wages, which we summarize here, are described in greater depth in the special study published in the dossier on the OFCE’s forecasts (Revue de l’OFCE, no. 136, November 2014).

An adjustment driven by moderation in wage increases …

Faced with falling demand, companies have adapted by making heavy cutbacks in employment in order to cut costs, which has led to a steep rise in unemployment. The number of jobless in the euro zone was 7 million higher in September 2014 than in March 2008. The situation is especially glum in countries like Greece, where the unemployment rate is 26.9%, Spain (24.2%), Portugal (13.8%) and Italy (12.5%). Only Germany has experienced a reduction in unemployment, with a rate of 5.0% of the active population.

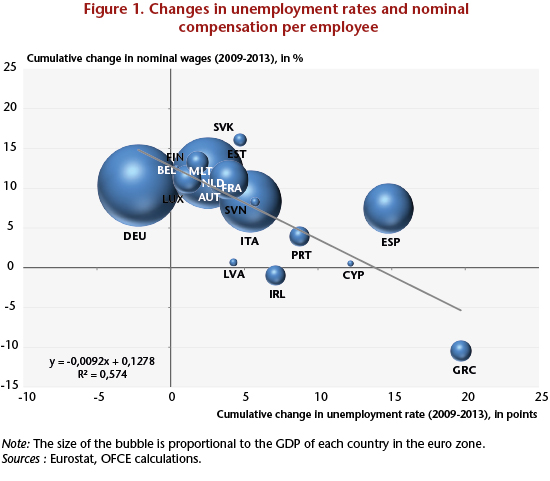

As is suggested by the Phillips curve, runaway unemployment has eventually affected the conditions governing wage increases, especially in the most crisis-ridden countries (Figure 1). While between 2000 and 2009 wage growth was more dynamic in the peripheral countries (3.8% annually) than in the countries in the euro zone core (+2.3%) [1], the situation reversed after 2010. Nominal wage growth slowed in the peripheral countries (0.8%), but stayed close to the pre-crisis rate (+2.6%) in the core countries. This heterogeneity is due to differences in how much unemployment has worsened in the different countries. According to Buti and Turrini (2012) [2] from the European Commission, reversing the trend in wage dynamics will be a major factor driving the rebalancing of current account positions in the euro zone.

Furthermore, an analysis at the macroeconomic data level masks the extent of the ongoing wage moderation, as the effects of the crisis are concentrated on the most vulnerable populations (young, non-graduate employees) earning the lowest wages. The deformation of the structure of employment in favour of more skilled and more experienced workers (see the OFCE post: On the difficulty of carrying out structural reforms in a context of high unemployment) is also pushing up mid-level wages. As can be seen in a number of studies based on an analysis of the macroeconomic data [3], wage growth after correcting for these composition effects is below the increase in the average salary.

… that compresses domestic demand and is not very effective in terms of competitiveness

Underlying this policy of deflationary adjustment through wages, what is important for companies is to improve competitiveness and regain market share. Thus, compared with the beginning of 2008, unit labour costs (ULC) [4] fell in the countries deepest in crisis (Spain, Portugal and Ireland), slowed in Italy and continued their upward progression in the countries in the euro zone core, i.e. those facing the least financial pressure (Germany, France, Belgium and the Netherlands).

The most significant adjustment took place in Spain. Deflated by inflation, its ULC has fallen by 14% since 2008, 13 points of which are explained by the recovery in productivity, which was achieved at the expense of massive cuts in employment. Real wages increased only 1% over the period. Conversely, in Italy, the adjustment has focused on wages, whose purchasing power has fallen by 5%. However, this decline was not sufficient to offset the fall in productivity, and thus to prevent an increase in the real ULC. In Germany, after the real ULC rose in 2008, real wages continued to rise, but less than gains in productivity. In France, real wages and productivity have risen in tandem at a moderate pace. The ULC, deflated by inflation, has thus been stable since 2009 but has still worsened compared to 2008.

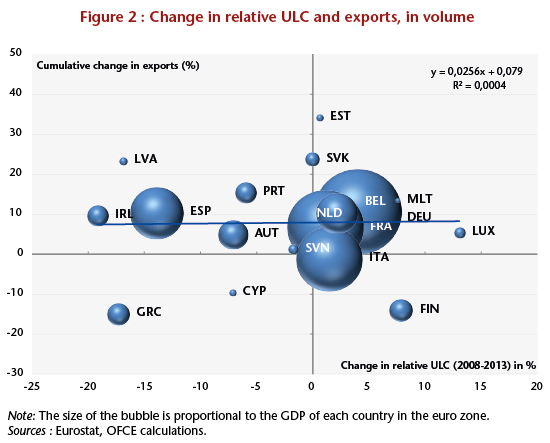

Even though this deflationary strategy is intended to restore business competitiveness, it is a double loser. First, as the strategy is being implemented jointly in all the countries in the euro zone, these efforts wind up neutralizing each other. Ultimately, it is the countries that carry the strategy furthest that win the “bonus”. Thus, among the euro zone’s larger economies, only Spain can really benefit due to the sharp reduction in its ULC, which reflects not only its own efforts but also some continued wage growth among its key partners. France and Italy are not experiencing any gain, and Germany has seen a deterioration in its ULC of about 3% between 2008 and 2013. Moreover, while the wage devaluation might have helped to boost activity, this will have been accomplished through a rebound in exports. But it is difficult to find any correlation between exports and wage adjustments during the crisis (Figure 2). These results have already been pointed out by Gaulier and Vicard (2012). Even if the countries facing the deepest crisis (Spain, Greece, Portugal) might gain market share, the volumes exported by each of them are in the short/medium term not very sensitive to changes in labour costs. This might be explained by companies’ preference to rebuild their margins rather than to lower export prices. Even in countries where the relative ULC fell sharply, the prices of exports rose significantly (6.2% in Greece, 3.2% in Ireland since 2008, etc.).

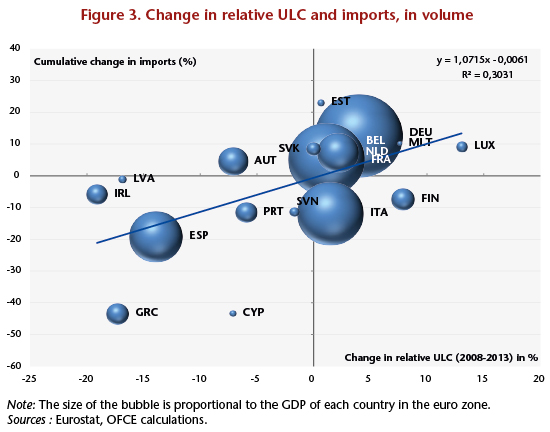

Finally, in an effort to improve their cost competitiveness, companies reduced their payroll by cutting employment and / or wages. This strategy of competitive disinflation results in pressure on household incomes and thus on their demand for goods, which slows the growth of imports. Indeed, in contrast to what is observed for exports, there is a close and positive relationship between changes in the relative ULC and in import volumes over the period 2008-2009 (Figure 3). In other words, the greater the adjustment effort in the ULC with respect to competitor countries, the slower the growth in import volumes.

This non-cooperative strategy to rebalance the current account can permanently affect an economic recovery in a context where reducing the debt of both private and public agents will become even more difficult if deflationary pressures are felt in an ongoing way (due to increases in real terms in debt and interest rates). The imbalances in the current accounts of the various euro zone countries will thus be dealt with mainly by a contraction of imports. The correction of such imbalances by means of a wage devaluation, as was the case in 2010-2011, is therefore doubly expensive: a low impact on competitiveness, relative to competitors, due to the simultaneous implementation of the strategy in the various euro zone countries, and an increased risk of deflation, making it more difficult to shed debt, thereby fuelling the possibility of a scenario of prolonged stagnation in the euro zone.

[1] Germany, France, Belgium and the Netherlands. The peripheral countries include Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece.

[2] Buti and Turrini (2012), “Slow but steady? Achievements and shortcomings of competitive disinflation within the Euro Area”.

[3] For a comparison of a number of euro zone countries at the start of the crisis, see ECB (2012), “Euro Area Labor Markets and the Crisis”. For the case of Spain, see Puente and Galan (2014), “Un analisis de los efectos composición sobre la evolución de los salarios”. Finally, for the French case, see Verdugo (2013) “Les salaires réels ont-ils été affectés par les évolutions du chômage en France avant et pendant la crise?” and Audenaert, Bardaji, Lardeux, Orand and Sicsic (2014), “Wage resilience in France since the Great Recession”.

[4] The unit labour cost is defined as the cost of labour per unit produced. This is calculated as the ratio between compensation per capita and average labour productivity.