The idea is very widespread that in France unearned income benefits from an especially low level of taxation and that the French system could be made fairer by simply raising this level. In an OFCE Note, we compare the taxation on capital income with that on labour income, and show that most of it is taxed just as highly. The reforms adopted in 2012 further increase the taxation of capital income. So there is little room for manoeuvre. However, there are tax loopholes and a few exceptions, the most notable being the current non-taxation of imputed rent (which benefits households that own their own residence).

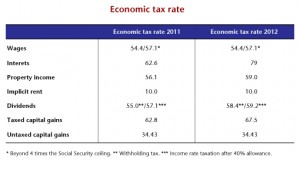

The table below compares the marginal tax rates for different types of income. The effective economic tax rates (including the “IS” corporate income tax, non-contributory social charges, the CSG wealth tax, social security taxes) are well above the posted rates. The interest, rental income, dividends and capital gains that are taxed are taxed at approximately the same level as the highest salaries. It is therefore wrong to claim that capital income is taxed at reduced rates. When it is actually taxed, this is at high levels.

The official tax rate on capital income increased from 29% in 2008 to 31.3% in 2011 due to a 1.1 percentage point increase in payroll taxes to finance the RSA benefit, a 1 point increase in withholding tax and a 0.2 point increase to fund pensions. The government has financed the expansion of social policy by taxing capital income. This rate will increase to 39.5% (for interest) and to 36.5% for dividends on 2012 income.

Should we advocate a radical reform: submission of all capital income to the tax schedule on personal income? This might be justified for the public image (to show clearly that all income is taxed similarly), but not on purely economic grounds.

With respect to interest income, this would mean ignoring the inflation rate. The 41% bracket would correspond to a levy of 108% on the real income of an investment remunerated at 4% with an inflation rate of 2%. For dividends, one must not forget that the income in question has already paid the “IS” tax; the 41% bracket (by eliminating the 40% allowance) would correspond to a total tax of 70%. We must make a policy choice between two principles: a single economic tax rate for all income (which paradoxically would lead to preserving a special tax on capital income) or higher taxation on capital income, since this goes mostly to the better-off and is not the fruit of effort (which paradoxically would lead to subjecting it to the same tax schedule as labour income, while forgetting the IS tax and inflation).

The problem lies above all in schemes that allow tax avoidance. For many years, the banks and insurance companies managed to convince the public authorities that it was necessary to make income from household financial capital tax exempt. Two arguments were advanced: to prevent the wealthy from moving their capital abroad; and to promote long-term savings and high-risk savings. Exemptions were thus made for PEA funds, PEP funds, and UCITS mutual funds. Governments are gradually pulling back from these exemptions. Two principles should be reaffirmed: first, all capital income should be subject to taxation, and tax evasion should be combated by European agreements on harmonizing tax systems; and second, it is the responsibility of issuers to convince investors of the value of the investments they offer – the State should not fiscally favour any particular type of investment.

There remains the possibility that wealthy families will succeed in avoiding taxes on capital gains through donations to children (alive or upon their death) or by moving abroad before taxation takes place. Thus, a wealthy shareholder can hold his securities in an ad hoc company that receives his dividends and use the company securities as collateral for loans from the bank, which then provides him the money needed to live. The shareholder thus does not declare this income and then passes on the company securities to his children, meaning that the dividends and capital gains he has received are never subjected to income tax.

The other black hole in the tax system lies in the non-taxation of imputed rent. It is not fair that two families with the same income pay the same tax if one has inherited an apartment while the other must pay rent: their ability to pay is very different.

Two measures thus appear desirable. One is to eliminate all schemes that help people avoid the taxation of capital gains, and in particular to ensure the payment of tax on any unrealized capital gains in the case of transmission by inheritance or donation or when moving abroad. The second would be gradually to introduce a tax on imputed rent, for example by charging CSG / CRDS tax and social security contributions to homeowners.

Having done this, a policy choice would be needed:

– Either to eliminate the ISF wealth tax, as all income from financial and property capital would clearly be taxed at 60%.

– Or to consider that it is normal for large estates to contribute as such to the running costs of society, regardless of the income the estates provide. With this in mind, the ISF tax would be retained, without comparing the amount of the ISF to the income from the estate, since the purpose of the ISF would be precisely to demand a contribution from the assets themselves.