Austerity in Europe: a change of course?

By Marion Cochard and Danielle Schweisguth

On 29 May, the European Commission sent the members of the European Union its new economic policy recommendations. In these recommendations, the Commission calls for postponing the date for achieving the public deficit goals of four euro zone countries (Spain, France, Netherlands and Portugal), leaving them more time to hit the 3% target. Italy is no longer in the excessive deficit procedure. Only Belgium is called on to intensify its efforts. Should this new roadmap be interpreted as a shift towards an easing of austerity policy in Europe? Can we expect a return to growth in the Old Continent?

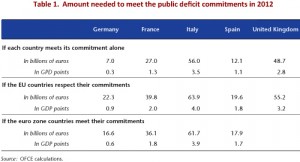

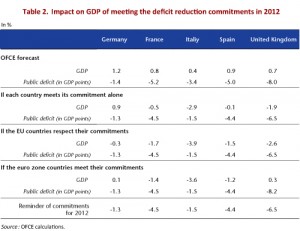

These are not trivial matters. An OFCE Note (no. 29, 18 July 2013) attempts to answer this by simulating three scenarios for fiscal policy using the iAGS model. It appears from this study that postponing the public deficit targets in the four euro zone countries does not reflect a real change of course for Europe’s fiscal policy. The worst-case scenario, in which Spain and Portugal would have been subject to the same recipes as Greece, was, it is true, avoided. The Commission is implicitly agreeing to allow the automatic stabilizers to work when conditions deteriorate. However, for many countries, the recommendations with respect to budgetary efforts still go beyond what is required by the Treaties (an annual reduction in the structural deficit of 0.5 percent of GDP), with as a consequence an increase of 0.3 point in the unemployment rate in the euro zone between 2012 and 2017.

We believe, however, that a third way is possible. This would involve adopting a “fiscally serious” position in 2014 that does not call into question the sustainability of the public debt. The strategy would be to maintain a constant tax burden and to allow public spending to keep pace with potential growth. This amounts to maintaining a neutral fiscal stimulus between 2014 and 2017. In this scenario, the public deficit of the euro zone would improve by 2.4 GDP points between 2012 and 2017 and the trajectory in the public debt would be reversed starting in 2014. By 2030, the public deficit would be in surplus (0.7%) and debt would be close to 60% of GDP. Above all, this scenario would lower the unemployment rate significantly by 2017. The European countries could perhaps learn from the wisdom of Jean de La Fontaine’s fable of the tortoise and the hare: “Rien ne sert de courir, il faut partir à point“, i.e. Slow and steady wins the race.