Spain: a 2018 budget on target, if the Commission likes it or not

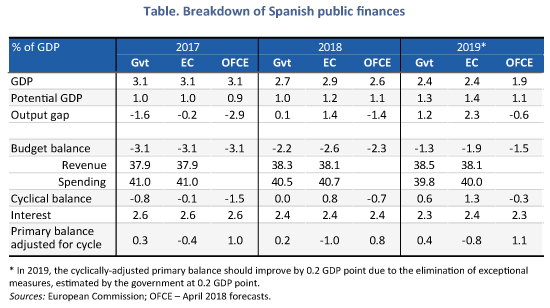

With a deficit of 3.1% of GDP in 2017, Spain has cut its deficit by 1.4 points from 2016 and has been meeting its commitments to the European Commission. It should cross the 3% threshold in 2018 without difficulty, making it the latest country to leave the excessive deficit procedure (EDP), after France in 2017. The 2018 budget was first presented to the European Commission on April 30 and then approved by Spain’s Congress of Deputies on May 23 amidst a highly tense political situation, which on June 1 led to the dismissal of Spain’s President Mariano Rajoy (supported by the Basque nationalist representatives of the PNV Party who had approved the 2018 budget a few days earlier). It should be passed in the Senate soon by another majority vote. The expansionary orientation of the 2018 budget, backed by the government of the new Socialist President Pedro Sanchez, does not satisfy the Commission, which considers the adjustment of public finances insufficient to meet the target of 2.2% of GDP included in the 2018-2021 Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). According to the hypotheses of the previous government, not only would the deficit fall below 3% but the nominal target would be respected.

Admittedly, while, given the strong growth expected in Spain in 2018, the public deficit will easily be below 3% in 2018 and therefore meet the requirements set in the EDP, the new budget act is not in line with the fiscal orthodoxy expected by Brussels. The lack of a People’s Party majority in Congress led ex-President Mariano Rajoy into strategic alliances with Ciudadanos and the PNV to get the 2018 budget adopted (with the hope, in particular, of avoiding early parliamentary elections), at the price of significant concessions:

– An increase in civil servants’ salaries of 1.75%[1] in 2018 and at least 2.5% in 2019, with a larger increase if GDP grows by more than 2.5% (estimated cost of 2.7 billion euros in 2018 and 3.5 billion in 2019 according to the outgoing government);

– Lower taxes for low-income households (via the increase in the minimum tax threshold from 12,000 to 14,000 euros income per year, tax credits for childcare expenses, assistance for disabled people and large families, and a reduction in tax on gross wages between 14,000 and 18,000 euros) (cost 835 million in 2018 and 1.4 billion in 2019);

– The revaluation of pensions by 1.6% in 2018 and by 1.5% in 2019 (cost of 1.5 and 2.2 billion), in addition to a rise of up to 3% in the old age and non-taxpayer minimum, and between 1% and 1.5% for the lowest pensions (cost 1.1 billion in 2018).

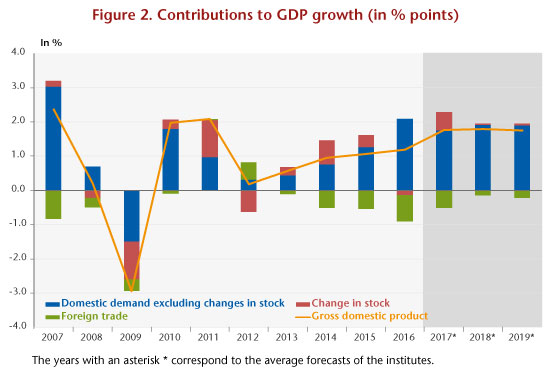

According to the former government, these measures will cost a little more than 6 billion euros in 2018 (0.5% of GDP) and nearly 7 billion in 2019 (0.6% of GDP). The revaluation of pensions should be partly covered by the introduction of a tax on digital activities (Google tax) in 2018 and 2019, with revenues of 2.1 billion euros expected. In the end, spending, which was expected to fall by 0.9 GDP point in 2018 based on the undertakings made in the previous 2017-2020 SGP, would fall by only 0.5 GDP point in the 2018-2021 SGP (to 40.5% of GDP) (Table). But above all, despite the tax cuts just introduced, the extra revenue expected from the additional growth should represent 0.1 GDP point (to 38.3% of GDP). In fact, the budget’s redistributive character, combined with the downward revision of the impact of the Catalan crisis on the economy (0.1% of GDP according to the AIReF [2]) led all the institutes (Bank of Spain, the Government, the European Commission) to raise their 2018 growth forecasts from last winter by 0.2 or 0.3 GDP point to bring it slightly below 3% (2.6% for the OFCE according to our April forecasts [3]).

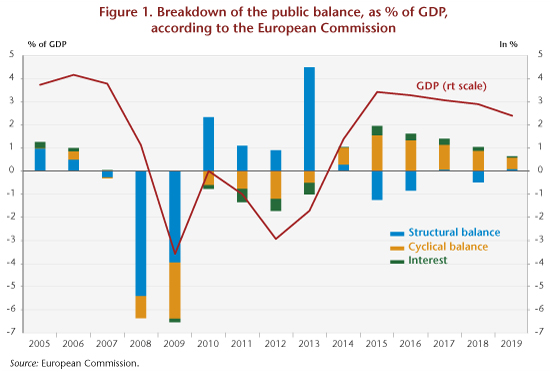

Nevertheless, beyond the shared optimism about Spanish growth, the calculations of the cost of the new measures differ between the Spanish authorities and the Commission. According to the government, the increase in growth should, as we have said, boost tax revenues and neutralize the expected cost of new spending. In 2018, the 0.9 percentage point reduction in the deficit (from 3.1% to 2.2%) would therefore be achieved by the 0.8 GDP point growth in the cyclical balance, combined with the 0.2 point fall in debt charges, with the structural balance remaining stable (fiscal policy would become neutral rather than restrictive as set out in the earlier version of the Pact). But this scenario is not shared by Brussels[4], for whom the cost of the measures, and in particular of the increase in civil servants’ salaries, is underestimated. Expenditures are expected to be 0.2 GDP point higher and revenue 0.2 GDP point higher than the government has announced. According to the Commission, the cyclical balance is expected to improve by 0.9 GDP point, but the fiscal impulse would worsen the structural balance by 0.6 GDP point. In these conditions, the deficit would bypass the 3% mark, but fiscal policy would clearly become expansionary and the 2.2% target would not be hit. The public deficit stood at 2.6% in 2018 (Figure 1).

Nevertheless, beyond the shared optimism about Spanish growth, the calculations of the cost of the new measures differ between the Spanish authorities and the Commission. According to the government, the increase in growth should, as we have said, boost tax revenues and neutralize the expected cost of new spending. In 2018, the 0.9 percentage point reduction in the deficit (from 3.1% to 2.2%) would therefore be achieved by the 0.8 GDP point growth in the cyclical balance, combined with the 0.2 point fall in debt charges, with the structural balance remaining stable (fiscal policy would become neutral rather than restrictive as set out in the earlier version of the Pact). But this scenario is not shared by Brussels[4], for whom the cost of the measures, and in particular of the increase in civil servants’ salaries, is underestimated. Expenditures are expected to be 0.2 GDP point higher and revenue 0.2 GDP point higher than the government has announced. According to the Commission, the cyclical balance is expected to improve by 0.9 GDP point, but the fiscal impulse would worsen the structural balance by 0.6 GDP point. In these conditions, the deficit would bypass the 3% mark, but fiscal policy would clearly become expansionary and the 2.2% target would not be hit. The public deficit stood at 2.6% in 2018 (Figure 1).

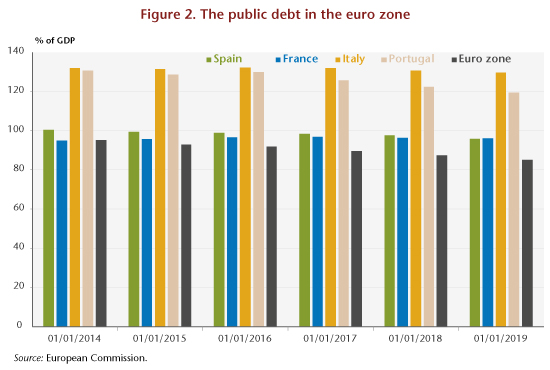

This more expansionary orientation of the 2018 budget results above all from the political considerations of the former Rajoy government and its effort to deal with the impossibility of governing (facts have demonstrated the fragility of this position). Nevertheless, the timing is ideal – because the only budget commitment required in 2018 is to cross the 3% deficit threshold in order to get out of the corrective arm of the SGP. The year 2018 therefore makes it possible to implement a generous fiscal policy, while crossing the 3% mark, without exposing the country to sanctions. The situation will be more delicate in 2019, when EU rules aimed at reducing a debt that is still well above 60% of GDP will be applied, notably by adjusting the structural balance (Figure 2).

This more expansionary orientation of the 2018 budget results above all from the political considerations of the former Rajoy government and its effort to deal with the impossibility of governing (facts have demonstrated the fragility of this position). Nevertheless, the timing is ideal – because the only budget commitment required in 2018 is to cross the 3% deficit threshold in order to get out of the corrective arm of the SGP. The year 2018 therefore makes it possible to implement a generous fiscal policy, while crossing the 3% mark, without exposing the country to sanctions. The situation will be more delicate in 2019, when EU rules aimed at reducing a debt that is still well above 60% of GDP will be applied, notably by adjusting the structural balance (Figure 2).

[1] https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2018/03/26/pdfs/BOE-A-2018-4222.pdf

[2] https://elpais.com/economia/2018/04/17/actualidad/1523949570_477094.html?rel=str_articulo#1526464987471

[3] See the Spain part of the dossier: https://www.ofce.sciences-po.fr/pdf/revue/11-155OFCE.pdf , pp 137-141.

[4] Nor by the AIReF.

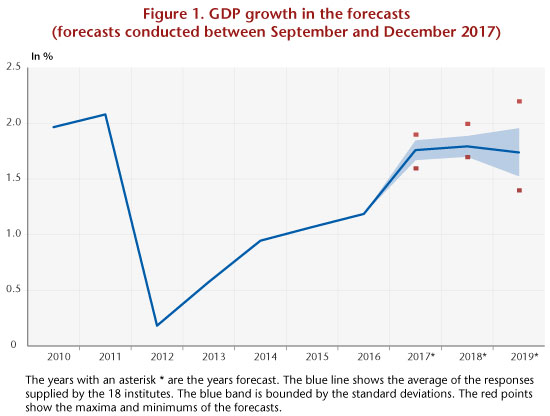

There is also debate over the forecasts for jobs and wages, in particular over the impact of the cutbacks in subsidized jobs, the effect of the policies to lower labour costs in 2019 (transformation of the CICE competitiveness tax credit into lower employer social contributions) and productivity (trend and cycle). On average, the unemployment rate should fall from 9.5% in 2017 to 8.8% in 2019, with forecasts ranging from 8.1% for the most optimistic to 9.2% for the most pessimistic. Some differences in the forecasts on wages can be attributed to differing assessments both of the degree of tension on the labour market and also of the impact on wages of the more decentralized collective bargaining set up in 2017. Wages are expected to rise by 1.8% in 2017 and on average by 1.9% in 2018 and 2% in 2019 (ranging from 1.3% for the lowest forecast to 2.6% for the highest).

There is also debate over the forecasts for jobs and wages, in particular over the impact of the cutbacks in subsidized jobs, the effect of the policies to lower labour costs in 2019 (transformation of the CICE competitiveness tax credit into lower employer social contributions) and productivity (trend and cycle). On average, the unemployment rate should fall from 9.5% in 2017 to 8.8% in 2019, with forecasts ranging from 8.1% for the most optimistic to 9.2% for the most pessimistic. Some differences in the forecasts on wages can be attributed to differing assessments both of the degree of tension on the labour market and also of the impact on wages of the more decentralized collective bargaining set up in 2017. Wages are expected to rise by 1.8% in 2017 and on average by 1.9% in 2018 and 2% in 2019 (ranging from 1.3% for the lowest forecast to 2.6% for the highest).