Argentina’s experience of debt crisis

By Augusto Hasman and Maurizio Iacopetta

There is still a lot of uncertainty around the possible paths that Greece can follow in the near feature. One possible path, which may be still averted by the current negotiation, is that Greece will default on the upcoming debt obligations (see graphics here for a detailed list of the upcoming Greek debt deadlines), thus spiraling into a currency and credit crisis and possibly resulting in a “Grexit”[1].

The Greek debt crisis shares some similarity with the Latin American debt crisis of the 1990s and early 2000s. In both Greece and Latin America, debts are mostly bond debts or debts to international institutions. Similarly to Greece, many Latin American countries had become more and more open in the decades before the crisis. The series of financial crises started with Mexico’s December 1994 collapse. It was followed by Argentina’s $95 billion default (the largest in history at that time, although later on Argentina resumed some of the payments), Brazil’s financial crisis (1998-2002) and Uruguay’s default (2002).

Argentina is viewed as benchmark for getting insights on the possible macroeconomic consequences of a Grexit, partly because it abandoned the peg with the dollar as a result of its mounting fiscal crisis. Nevertheless, some have pointed out at marked differences between the two economies, in terms of industry structure as well as trade composition (see here for instance).

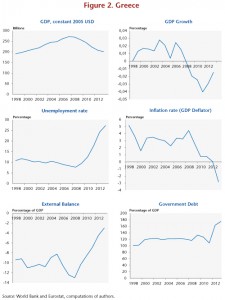

Here, we review the different steps followed by Argentina during the crisis and propose some statistics related to developments of key economic indicators in Argentina before and after the crisis. For comparison purposes, we also provide key figures of the Greek’s economy.

Argentina and Greece at time of considerable stress

Greece entered the European and Monetary Union in 2001, meaning an irrevocably fixed exchange rate regime and the adoption of the Euro as legal tender. By early 2010, Greece risked defaulting on its public debt and had to call for a financial rescue to international institutions. On the other hand, at time of the crisis, Argentina had its currency, the peso, ‘immutably’ fixed to the US dollar on a one-to-one basis. As today’s Greek situation, when Argentina defaulted in late 2001, the country’s economy and government were both experiencing considerable stress. 2001 was the third consecutive year of serious recession for Argentina, foreign direct investment had virtually stopped, and inflation, interest rates and the budget deficit all were soaring. The IMF had provided loans to keep the peso stable, on the condition that the government would adopt fiscal and monetary discipline. Argentina’s economic problems became a serious crisis in December 2001, when the IMF denounced the government’s inability to put its financial house in order and suspended its loans. This development was followed almost immediately by a banking crisis and violent public protests that produced a rapid succession of six presidents in two weeks. Figure (1) depicts the behavior of Argentinian key economic indicators before and after the 2001 devaluation. Figure (2) shows the Greek’s indicators since 1998[2]. A quick inspection of the two figures reveals that:

-The magnitude of the decline of Greece’s GDP during the crisis, counting from its highest point in 2008 is roughly the same as that observed in Argentina during a recessionary period before the devaluation: 25%.

– The rise in the unemployment rate has been much more severe in Greece that in Argentina. In Argentina, unemployment, rose from 12.4% in 1998 to 18.3% in 2001 whereas in Greece it went up from less than 10% in 2008 to over 25% to this day. Both in Argentina and in Greece the inflation had been relatively low before the debt crisis; in fact in Greece it has even been negative in recent years.

The recovery

What is somewhat surprising is what happened in Argentina after the crisis.

First, after a short period of turbulence, the Gross Domestic Product, in constant dollars, began to rise at an astonishing pace of almost 10 percent per year, until the 2007-08 financial crisis. Second, the unemployment rate declined from 18 percent to about 7 percent. Third, the poverty rate went down even below the level observed in the heyday of the pegged exchange rate. But financial indices deteriorated. First the difficulties in accessing external credits and the loss of credibility of the government pushed up the bond spreads from 4000 basis points before the crisis to ten times as much after the crisis. Second, the inflation rate seems to have stabilized at a double digit figure. According to some scholars (see for instance Alberto Cavallo “Online and official price indexes: Measuring Argentina’s inflation” Journal of Monetary Economics, 2012) there has been a systematic attempt by government authorities to greatly underestimate or underreport the inflation rate. Therefore, the GDP gain may not be as high as the one showed in Figure 1. Although the Argentinian economy has gone into a sustained period of growth, it would be unwarranted to make an automatic link between the renaissance of the Argentinian economy and the dramatic conclusion of the crisis with the abandonment of the peg and the debt default.

Some have pointed out that the recovery period coincided with a boom in the price of primary commodities (soybeans), which notoriously account for an important part of Argentinian exports. Clearly the increase in commodity prices has been a windfall for Argentinian agricultural producers with possible trickling effects on the rest of the economy. Yet, the magnitude of the windfall itself can hardly account for the large GDP gains. In fact, soybean was sold in Iowa at an average price of $4.57 per bushel in the year 2000 and at $5.88 in the year 2005. Only since 2010 prices have gone up substantially more, but at that point, the Argentinian economy had already gone through almost a decade of economic boom. Furthermore, the high price of soybeans in the second half of the 1990s (it was $7.32 in 1997) does not seem to have been helpful to avoid the economic depression. The route to recovery in Argentina has been characterized by setbacks, but also by a number of inventiveness that may have played a role in defraying the shock of the crisis.

Bank runs

At the end of November 2001, rising worries about a peso devaluation and a deposit freeze, increased overnight interest rates sharply. Additionally, spreads between US Treasury bonds and Argentine government bonds increased by 5,000 basis points. In order to stop the effects of a bank run, the Minister of Economy Domingo Cavallo announced a freeze on bank deposits. As in Greece, this measure considerably reduced the capacity of depositors to withdraw and manage their bank deposits. The deposit freeze had even accentuated the feeling among the population that a crisis was going to explode, and a series of demonstrations surged along the country. Subsequently, the IMF announced a cut of its support to Argentina, as it had failed to meet the conditions tied to the rescue program and Argentina lost its last source of funding. With a total amount of almost USD 22bn in 2000 and 2001, Argentina was the largest debtor the IMF had at the time. In the protests and raiding that followed, 24 people died. President De La Rúa and his cabinet resigned soon after these events.

Claims after the currency devaluation

The government decided to ‘pesofy’ the loans at a rate of A$1 (Argentinean peso) for each dollar (USD) owned by banks and A$1.4 for each dollar deposited in a bank. Alternatively, people could get a government bond (Boden 2012), that paid A$775.12 for a nominal of USD$100, when the official dollar was 4.35A$/USD. A less attractive bond was issued the following year: it paid A$930 for a nominal of USD$100 but could only be converted at 8.95A$/USD.

Massive use of money-bonds

In 2001, different Argentinean provinces started to print their own quasi-currencies, several emergency bonds (technically called Treasury Bills for Debt Settlement) issued between 2001 and 2002. They were created as a way of alleviating the enormous financial and economic crisis that occurred in Argentina in 2001. These bonds were considered a “necessary evil” that initially allowed to cover the absence of money circulation. While at first the issuing of these quasi-currencies was controversial, it later gained acceptance partly because of the size of the issue and partly because of the magnitude of the crisis. These bonds circulated in parallel to the Argentinean peso. They could be used to pay some taxes, shopping and even salaries. As the pesos, they were denominated in different values 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 to facilitate transactions (nominally equivalent to a Convertible Peso). The most popular bond was the Patacon that was issued in Buenos Aires. This bond had an interest rate of 7% and there were two series (Series A maturing in 2003, while the B in 2006). It is estimated that the total issue amount for the Patacons only reached 2.705 millions. Once the economic recovery of Argentina started in late 2003, the government honored 100% the principal of these outstanding bonds, and even the interests were eventually paid. Up to 13 quasi-currencies were issued by different provinces during that period.

Credit

Figure (1) shows that in Argentina the “Sovereign Bond Interest Rate Spreads, basis points over US Treasuries” has been growing for the last 18 years showing the difficulties Argentina has had in accessing to international credit market. The difficult access to foreign funding has pushed the Argentinean government to get financed internally through the central bank, retirement funds and the tax agency. The high inflation that resulted from this policy (close to 26%, unofficial measures) has made the use of local credit extremely expensive for companies and households. However, as Argentina started posting large surpluses on the fiscal and current accounts after the default and large devaluation of the peso, access to foreign finance became less urgent. Argentina took a hardline approach against creditors. By 2010, 92% of the Argentine defaulted debt had been restructured. However, ongoing litigation by holdout creditors could lead to a new Argentine default in the near future.

In conclusion, the Argentina exit from the debt crisis through a default did not have long lasting dramatic consequences on real activities as many had anticipated. The crisis meant a transfer of wealth from depositors to debt holders and promoted exports. After an abrupt decline, GDP quickly started its ascent and the country experienced high rates of growth in the 2000s, which reduced significantly unemployment.

Nevertheless the period right after the devaluation was characterized by political instability, large macroeconomic fluctuations and social revolts. The political stability that followed, might have played a role in sustaining growth, but the rate of inflation climbed at double-digit figures and the various price control mechanism introduced by the government have created a lot of frictions in the business sector. Finally, the increasing isolation of the government from the international political arena partly, due to the outstanding litigation with international lenders, could, in the long run, have negative repercussion on trade.