The infinite clumsiness of the French budget

By Xavier Timbeau, @XTimbeau

In the draft budgetary plan presented to the European Commission on 15 October 2014, it is clear that France fails to comply with the rules on European governance and its previous commitments negotiated in the framework of the European Semester. As France is in an excessive deficit procedure, the Commission, as guardian of the Treaties, has no choice a priori but to reject the country’s budget plan. If the Commission does not reject the plan, which departs very significantly, at least in appearance, from our previous commitments, then no budget could ever be rejected.

Recall that France, and its current President, have ratified the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Growth (the “TSCG” came into force in October 2012), which had been adopted by the Heads of State in March 2012. There was talk during the 2012 presidential campaign of renegotiating it (which raised the hopes of the southern European countries), but the urgency of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, among other factors, decided otherwise. France has implemented the provisions of the TSCG in Organic Law 2012-1403, for example by setting up a new fiscal council, the Haut Conseil des Finances Publiques, and establishing a multiannual system for tracking the trajectory of public finances based on structural balances (that is to say, adjusted for cyclical effects).

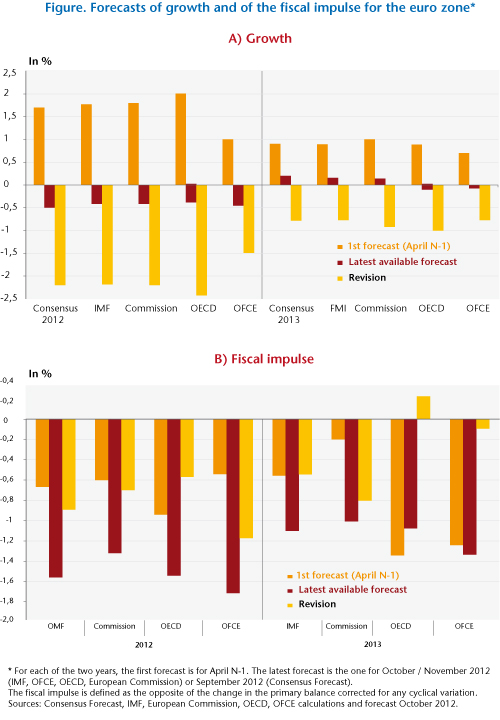

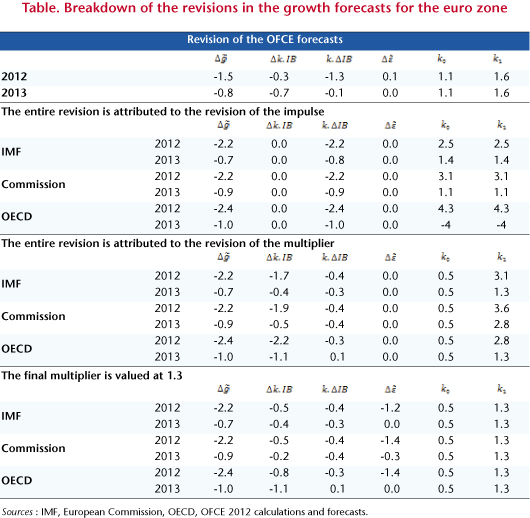

Everything seems to indicate that France had accepted the highly restrictive framework that had been established by the “Six-Pack” (five regulations and one directive, dated 2011, which reinforce the Stability and Growth Pact and which specify a timetable and parameters) and then reinforced by the TSCG and the “Two-Pack”. France’s good will was also evident when it presented its 2014 draft budgetary plan in October 2013 and a stability programme in April 2014, which more than complied. It was at a press conference in September 2014 that the French government announced that the deficit reduction target for 2015 would not be met. Low growth and low inflation were the arguments made there for a serious revision of the economic situation, which was presented as a truthful assessment. The same situation arose in 2013, with the nominal target then being set while underestimating the fiscal multipliers. However, the timing and magnitude of the adjustments had been respected, and a postponement was granted.

So until the press conference, no major difficulty had been posed to the workings of the Treaty. One of the innovations of the TSCG was in fact to no longer aim at a nominal target (3%) but to focus on the structural effort. If the economic situation proves to be worse than expected, then the nominal deficit target is not met (which is the case). In this situation, the objective is the structural effort. In the 2014-2017 Stability Programme of April 2014, the structural effort announced (page 13) is a 0.8 GDP point reduction in the structural deficit in 2015, following 0.8 GDP point in 2014. The excessive deficit procedure (also set out in a vade-mecum of the Commission) requires a minimum structural effort of 0.5 GDP point and that the mechanisms for achieving this be set out precisely.

It is here that the 2015 budget bill represents a concrete violation of the treaty. The effort in 2014 is now only 0.1 point, with 0.2 point announced in 2015. These figures are unacceptable to the Commission. How can such a provocative change be explained? Several factors are behind this. The first is a change in the method of booking the CICE tax credit, which means recording in 2015 the expenses generated in 2015 and paid in 2016. As the CICE ramps up, this comes to 0.2 GDP point less in France’s fiscal effort. The second is a change in the hypothesis for potential growth. Instead of 1.5% potential growth in the 2014-2017 stability programme, this is assumed to be 1.2% over the 2014-2017 period. Using a constant percentage method, the effort would have been 0.5 GDP point in 2014 and 0.6 point in 2015. The difference with the April 2014 stability programme is due to the revision downwards of inflation and to several changes in the measurements. A new presentation of the same budget, with a marginal modification of the economic situation, is marked by the absence of structural effort. Not only will the nominal target not be achieved, but furthermore the structural effort for 2014 and 2015 is abandoned – with no change in policy! Worse, this draft budget implies that the nominal target is not being achieved because the structural effort was not made in 2014 and won’t be in 2015.

The government, nevertheless, pleads extenuating circumstances. Why change the assumptions for potential growth while not having kept the previous accounting standards for presenting France’s 2015 draft budgetary plan? An effort of 0.6 GDP point in 2015 instead of the previously announced effort of 0.8 GDP point would not have posed any problems for the Commission, which itself had made overly high estimates of potential growth (as also in its remarks on the 2014 draft budgetary plan, which the Council did not adopt in November 2013). It would have been easy to answer that one does not change assumptions of potential growth every 6 months, and that this is furthermore the purpose of this concept and the reason for its introduction in EU Treaties and guidelines: to avoid a pro-cyclical character in fiscal policy, to avoid tightening up budgets at a time when bad news is piling up. It would have been accepted that the Commission had a lower assessment than France, but potential growth is not observed, and its assessment is based on numerous hypotheses. It is not, for instance, specified in the treaties or regulations whether potential growth is to be assessed in the short term or the medium term. But the Commission considers (in the 2012 Ageing Report) that France’s medium-term growth potential was 1.7% per year (on average 2010 to 2060) and 1.4% in 2015. Above all, nothing obliges France to adopt the hypothesis of the Commission. EU regulation 473/2011 demands that the hypotheses be made explicit, and outside opinions might also be requested. French Organic Law 2012-043 states that, “A report attached to the draft budgetary plan (LPFP) and giving rise to parliamentary approval states: … 9) The procedures for calculating the structural effort referred to in Article 1, the distribution of this effort among the various sub-sectors of government, and the elements used to establish a correspondence between the notion of the structural effort and the notion of the structural balance; 10) The hypotheses of potential gross domestic product used in planning the public finances. The report presents and justifies any differences from the estimates of the European Commission” – which gives the government good control over the hypothesis for potential growth and makes the parliament sovereign, the final judge.

Does a truth check need to be conducted on potential growth so as to significantly alter this crucial hypothesis in the presentation of the budget? Should a truth process lead to presenting a budget as almost neutral when it reflects crucial, expensive policy choices (to finance business competitiveness by cutting public spending and increasing taxes on households)? Is the Commission’s hypothesis more relevant because it has been continuously revised every 6 months for 5 years now? Couldn’t it be explained that the French government’s ambitious programme of structural reform would help to increase potential growth in the future (unless the government doesn’t believe this)? Aren’t the CICE and the Responsibility Pact a sufficient pledge of the renewed vitality of a productive system that will lead to boosting potential growth? Would it be better to follow the advice of the authors of a report for the French Council of Economic Analysis (CAE) on potential growth who did not risk producing a new estimate? Isn’t it the subject of growth that needs to be discussed (constructively and technically, in discreet fora) with the Commission, rather than engaging in an explicit breach of EU rules? In the 2015 draft budgetary plan, it is written (page 5): “the trajectory is based, out of caution, on a downward revision of potential growth from the previous budgetary plan, by taking the European Commission’s latest estimate of potential growth (spring 2014)”. What kind of caution is this that looks more like a blunder with terrible consequences? Is it the mess that the government was in at end August 2014 that permitted this state of infinite clumsiness?

It is impossible to justify the presentation made: the Commission will rebuke France, which will not react, since it is sure of its rights (as the government has already stated). The Commission will then ramp up the sanctions, and it is unlikely that the Council will stop this process, especially as the decisions are to be taken by a reverse qualified majority vote. There will be a new round of French-bashing, which will merely show the futility of the process, because France will not deviate from the path it has chosen for its public finances. This will undercut France’s persuasiveness and influence at the very time that a 300 billion euro investment plan is being developed, which is sought only by France and Poland (according to rumors), which risks derailing a rare initiative that could get us out of the crisis.

In letting the muffled fury of the technocracy express its dissatisfaction with France, what will come out is the fragility of “European governance”. But this governance relies solely on the denunciation of France and the consequent peer pressure. France could be fined, but neither the Council nor the Commission have any instruments to “force” France to meet Treaty requirements. This is the weakness of “European governance”: it works only if the member states voluntarily adhere to the rules. It is thus governance in name only, but despite this it is the foundation underpinning the path out of the sovereign debt crisis. The European Central Bank intervened in the summer of 2012 because stronger governance of public finance was intended to solve the “free rider” problem. The (numerous) critics of the European Central Bank’s intervention have broadly denounced the hypocrisy of the Treaty, which guarantees nothing since it is based on the voluntary discipline of the member states. Its violation by France and the impotence of the Commission and the Council will be such a demonstration of this weakness that there is concern that the house of cards might collapse.

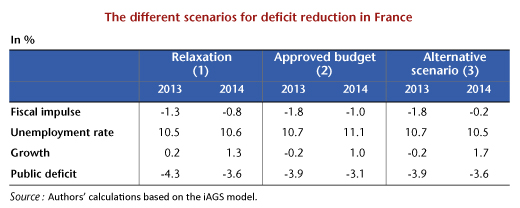

France could revise its draft budget and add measures that, in the new accounting system and with a lowered estimate of potential, would enable it to fulfil its April 2014 commitment on its structural effort. This scenario is highly unlikely, and that’s a good thing (see the post by Henri Sterdyniak). It’s unlikely, because the almost 2 points of VAT at the full rate required to achieve an effort of 0.8% of GDP (and thus without compensating for the delay in 2014) would not be approved by the French Parliament. And it’s good because this would trigger a recession (or serious slowdown) in France and a completely unacceptable rise in unemployment simply to save face for the Commission and diligently apply European legislation.

It would have been more clever to stick to the hypotheses (and methods) of the 2014 stability program, France’s Haut Conseil would have protested, the Commission would have complained, but Europe’s rules of governance would have been saved. They say that statistics are the most advanced form of lying. Between two lies, it’s best to choose the less stupid.