The 2018 European economy: A hymn to reform

By Jérôme Creel

The OFCE has just published the 2018 European Economy [in French]. The book provides an assessment of the European Union (EU) following a period of sharp political tension but in an improving economic climate that should be conducive to reform, before the process of the UK’s separation from the EU takes place.

Many economic and political issues crucial to better understanding the future of the EU are summarized in the book: the history of EU integration and the risks of disintegration; the recent improvement in its economic situation; the economic, political and financial stakes involved in Brexit; the state of labour mobility within the Union; its climate policy; the representativeness of European institutions; and the reform of EU economic governance, both budgetary and monetary.

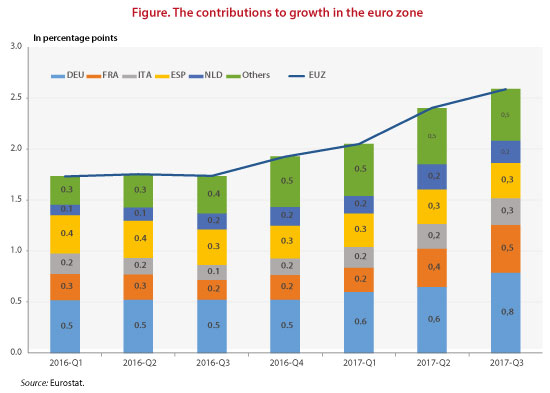

The year 2018 is a pivotal year prior to the elections to the European Parliament in spring 2019, but also before the 20th anniversary of the euro on 1 January 2019. The question of the euro’s performance will be central. However, in 2018 gross domestic product will finally begin to increase at well above its pre-crisis level, thanks to renewed business investment and the support of monetary policy, henceforth unhindered by fiscal policy.

The year 2018 will also mark the beginning of negotiations on the future economic and financial relationship of the United Kingdom and the EU, after at end 2017 the two parties found common ground on arrangements for the UK leaving the Union. The EU’s renewed growth will reduce the potential costs of the divorce with the British and could also lessen Europeans’ interest in this issue.

Brexit could have served as a catalyst for reforming Europe; the fact that the mechanisms for this may now seem less crucial to the EU’s future functioning should not take away from the reforms needed by the EU, as if these were superfluous. In the political and monetary fields, there is a great need to strengthen the democratic representativeness of EU institutions (parliament, central bank) and to ensure the euro’s legitimacy. In the fields of fiscal and immigration policy, past experience has demonstrated the need for coordinated tools to better manage future economic and financial crises.

There is therefore an urgent need to revitalize a project that is over sixty years old, one that has managed to ensure peace and prosperity in Europe, but which lacks flexibility in the face of the unpredictable (crises), which lacks vigour in the face of the imperatives of the ecological transition, and which is singularly lacking in creativity to strengthen the convergences within it.