European Semester: assessing the aggregate fiscal stance is good, discussing about its economic impact is better

On November the 26th, the ECFIN launched the European Semester and published the 2016 Annual Growth Survey and the Euro Area policy recommendation. The ECFIN states that the large spillovers from fiscal policy decisions and the current constraints on the single monetary policy call for strengthened attention to the aggregate fiscal stance at the euro area level. The recommended aggregate fiscal stance should take into account the cyclical position of the euro area. Moreover, a broadly neutral aggregate fiscal stance for the next years in the euro area appears appropriate to ECFIN in light of downside risks to growth and the persistent economic slack.

Opening the debate about the aggregate fiscal stance constitutes an important step in the improvement of the macroeconomic policy framework in the EA. In fact, the crisis that Euro zone has been facing since 2012 can be explained to a large extent by the fragilities in the monetary union. The lack of economic policy coordination emerged as one of the most important weaknesses. Before the crisis, the ECB was left alone to deal with common shocks while the fiscal policy was supposed to manage asymmetric shocks. Furthermore, the fiscal policy was supposed to safeguard public debt sustainability. This double objective was supposed to be assured by the compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) rules. This framework failed during the crisis. First, the rules of the SGP were focused only on public debt sustainability and neglected the impact of fiscal policy on macroeconomic stabilization. Second, the decentralization of the procedures resulted in a bad aggregate outcome. The asymmetry in the rules implies ill-calibrated adjustments in deficit countries while anything forces countries with fiscal space to implement growth supportive policies.

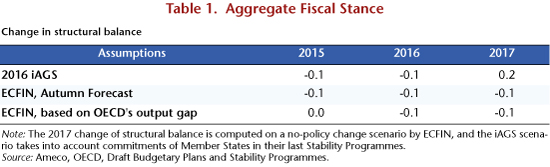

In order to assess about the global orientation of fiscal policy the weighted sum of changes in structural balances is the traditional indicator used in the European Semester. This figure evaluates the evolution of deficits in the long run, once the cyclical effects are purged. This figure depends crucially on the way structural deficits are calculated and hence on the assumptions about the potential output used: even under common budgetary assumptions, the evolution of structural balance can evolve in different ways (see lines 2 and 3 of the table 1, which are computed using the same assumptions in terms of fiscal policy). On the basis of this indicator, the aggregate fiscal stance in the euro area is neutral or slightly expansionary in 2015 and 2016. This assessment is shared by the 2016 independent Annual Growth Survey (iAGS). On the basis of the announcements of the Member States in their Stability Programmes, the iAGS team forecast that the fiscal consolidation will start again in 2017. This result differs with ECFIN forecasts, based on a no-policy change scenario that only takes into account the measures already implemented.

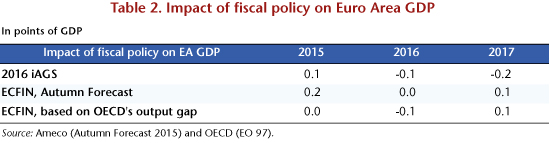

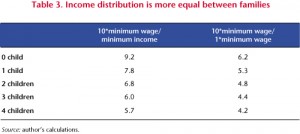

If the change of the structural balance shows that fiscal policy is broadly neutral in the euro area as a whole, the assessment of its economic impact needs to be completed. In the 2016 independent Annual Growth Report, we propose a new way to compute the aggregate fiscal stance that takes into account the most recent advances in the literature. According to several authors the multipliers of public expenses – which are decreasing in most of the bigger euro area economies– are higher than those associated with tax changes –which are decreasing and should have an expansionary impact. This is particularly true when output gaps are negative. Hence, the proposed indicator of the aggregate fiscal stance proposed is based on a weight that takes into account the macroeconomic impact of fiscal policy.

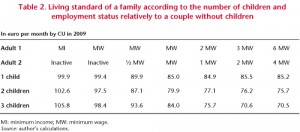

When the composition and the localisation of the fiscal impulses are taken into account, the assessment of the aggregate fiscal stance is modified. According to our calculation, fiscal policy will be slightly contractionary in 2016 (-0.1 point of GDP, table 2) in spite of the decrease in the aggregate structural balance. This paradox can be explained by the localisation of the impulsion, which has low impact in Germany and the composition of the expansion in Italy and in Spain (based on large tax cuts with a low multiplier partially compensated by an effort in expenses with a high multiplier).

The apparent paradox of a fiscal loosening with recessionary effects raises the matter of the fiscal space –expansionary policies should be larger in unconstrained countries– and the flexibilities in the application of SGP –expansion should be done in countries with high multipliers. Analyzing the situation of each Member State vis-à-vis the SGP, it appears that very few countries have fiscal space with respect to the rules of the SGP. According to the ECFIN analysis of Draft Budgetary Plans, only Germany would have some fiscal space but the efficiency of a timid German based stimulus would be limited, at least from a GDP point of view. This raises new questions and particularly about the creation of a common fiscal capacity that would enable implementation of a counter-cyclical budgetary policy, especially when there is no scope for monetary policy like a situation of liquidity trap and deflation. This is the rational of the Juncker Plan that aims to increase investment in the euro zone. However, the plan relies on unrealistic leverage assumptions and the selection of investment projects, based on the profitability of the project, may lead to a pro-cyclical bias. This plan may not be sufficient to generate the demand shock needed to escape from the Zero Lower Bound, suggesting that a permanent is needed.Taking into account the very high levels of unemployment and underemployment, even the highest value of the fiscal impulse (+0.1% GDP) is far too low to deliver significant stimulus. A coordinated increase of public investment with a focus on the Europe 2020 targets would be a proper policy change for a more balanced economic policy. With the implementation of the golden rule of public investment, such a stimulus could be achieved in line with the European fiscal rules.