A fall in the unemployment rate according to the ILO: the false good news

By Bruno Ducoudré and Eric Heyer

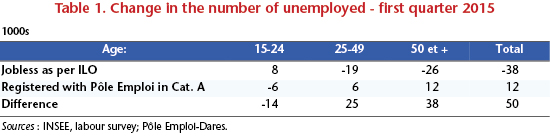

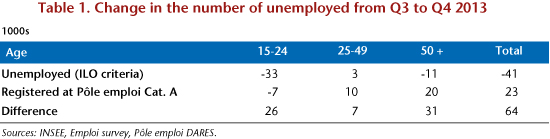

Two days following the announcement by France’s unemployment agency Pôle Emploi of an increase in Class A job seeker registrations in April, which comes on top of a first quarter increase, the INSEE statistics agency has published its estimate of the unemployment rate. Under the definition of the International Labour Office (ILO), the unemployment rate in metropolitan France fell by 0.1 point in the first quarter of 2015, meaning 38,000 fewer unemployed than in the fourth quarter of 2014. But according to Pôle emploi, over this same period the number of registered Class A job seekers rose by 12,000. In one case, unemployment is falling; in the other, it is rising: this does not make for a clear diagnosis of what’s happening with unemployment at the start of the year.

What accounts for the different diagnoses of the INSEE and Pôle Emploi?

In addition to differences in methodology (a labour survey for the ILO, administrative data for Pôle emploi), note that to be counted as unemployed according to the ILO, three conditions have to be met: a person must be unemployed, available to work and conducting an active job search. Simply registering at the job centre is not sufficient to meet this last condition. So someone who is registered in Class A [1] at Pôle Emploi but is not conducting an active search is not counted as unemployed according to the ILO. The ILO criteria are thus more restrictive. Historically, the number of unemployed registered at the job centre is higher than that calculated according to the ILO for persons aged 25 and over. Young people under age 25 generally have less incentive to register at the job centre [2].

Except for the under-25s, the unemployment figures from Pôle Emploi are therefore worse than those for the ILO and hence the INSEE (Table 1). The explanation is as follows. In labour market conditions that have worsened considerably, some unemployed people have become discouraged and are no longer actively seeking employment: they are thus no longer counted as unemployed according to the ILO. Yet they are continuing to update their status with the job centre and thus remain registered as unemployed in Class A. This results in an increase in the “halo” of the unemployed, i.e. people who want to work and are readily available but are not actively seeking a job. This unemployment “halo” has increased by 71,000 people in one quarter.

In first quarter 2015, the ILO-based unemployment rate fell for the wrong reasons

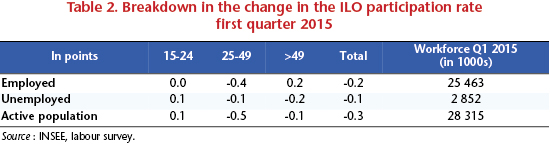

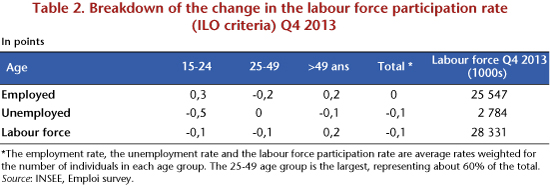

There are two reasons why the unemployment rate may fall: the first, virtuous reason is that people are exiting unemployment due to an improvement in the labour market; the second, less rosy reason is that some unemployed people are drifting into inactivity. The latest ILO statistics highlight that the 0.1 point fall in the unemployment rate was due entirely to the decline in the labour force participation rate – which measures the percentage of people in the population aged 15 to 64 who are active – and not to a recovery in employment, which, on the contrary, has declined. So the drop in the unemployment rate is due not to a recovery in employment, but to discouragement among unemployed people who are no longer actively seeking work (Table 2).

More specifically, the entry of young people into the labour market at a time when employment is declining is being reflected in a 0.1 point rise in joblessness in this category. Among seniors, the employment rate is continuing to increase (0.2 points) due to the postponement of the effective retirement age. It is true that ILO unemployment is falling among seniors, but the rising numbers in this age group enrolling at the job centre (Table 1) undoubtedly reflects a change in their job search behaviour: more and more of them are no longer making a job search and are now classified in the “halo” of unemployment.

Ultimately, the fall in the ILO-defined unemployment rate, which is marked by both a lack of recovery in employment and discouragement among some of the unemployed, is not such good news.

[1] People registered in Class A have not worked at all, even on reduced hours, unlike those registered in Classes B and C.

[2] To be entitled to unemployment compensation and to receive back-to-work assistance (“ARE”), 122 days of affiliation or 610 hours of work must be shown during the 28 months preceding the end of the job contract.