Oil: carbon for growth

By Céline Antonin, Bruno Ducoudré, Hervé Péléraux, Christine Rifflart, Aurélien Saussay

This text is based on the special study of the same name [Pétrole : du carbone pour la croissance, in French] that accompanies the OFCE’s 2015-2016 Forecast for the euro zone and the rest of the world.

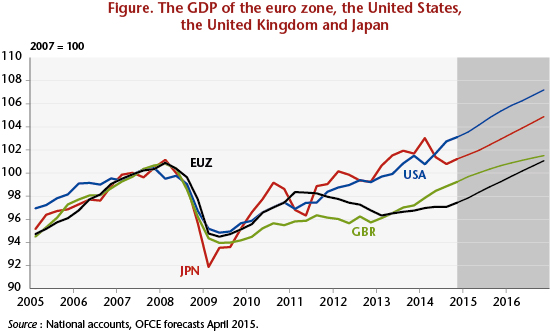

The 50% fall in the price of Brent between summer 2014 and January 2015 and its continuing low level over the following months is good news for oil-importing economies. In a context of weak growth, this has resulted in a transfer of wealth to the benefit of the net importing countries through the trade balance, which is stimulating growth and fuelling a recovery. Lower oil prices are boosting household purchasing power and driving a rise in consumption and investment in a context where companies’ production costs are down. This has stimulated exports, with the additional demand from other oil-importing economies more than offsetting the slowdown seen in the exporting economies.

That said, the fall in oil prices is not neutral for the environment. Indeed, the fall in oil prices is making low-carbon transportation and production systems less attractive and could well hold back the much-needed energy transition and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG).

This oil counter-shock will have a favourable impact on growth in the net oil-importing countries only if it is sustained. By 2016, the excess supply in the oil market, which has fuelled by the past development of shale oil production in the United States and OPEC’s laissez-faire policy, will taper off. Unconventional oil production in the United States, whose profitability is uncertain at prices of under 60 dollars per barrel, will have to adjust to lower prices, but the tapering off expected from the second half of 2015 will not be sufficient to bring prices down to their pre-shock level. Brent crude prices could stay at about 55 dollars a barrel before beginning towards end 2015 to rise to 65 dollars a year later. Prices should therefore remain below the levels of 2013 and early 2014, and despite the expected upward trend the short-term impact on growth will remain positive.

To measure the impact of this shock on the French economy, we have used two macroeconometric models, e-mod.fr and ThreeMe, to carry out a series of simulations. These models also allow us to assess the macroeconomic impact, the transfers in activity from one sector to another, and the environmental impact of the increased consumption of hydrocarbons. The results are presented in detail in the special study. It turns out that for the French economy a 20 dollar fall in oil prices leads to additional growth of 0.2 GDP point in the first year and 0.1 point in the second, but this is accompanied by a significant environmental cost. After five years, the price fall would lead to additional GHG emissions of 2.94 MtCO2, or nearly 1% of France’s total emissions in 2013. This volume for France represents nearly 4% of Europe’s goal of reducing emissions by 20% from 1990 levels.

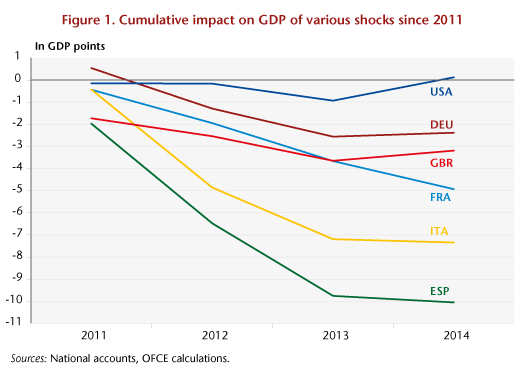

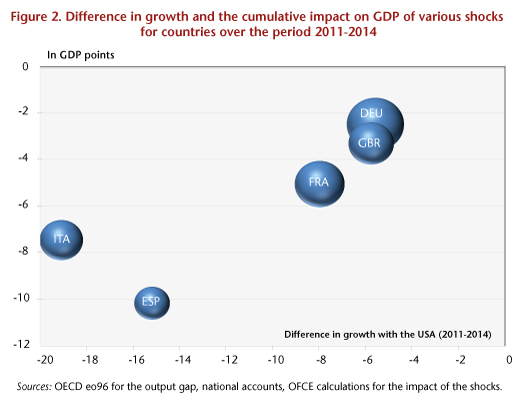

The simulations using the French e-mod.fr model can be extended to the major developed economies (Germany, Italy, Spain, the USA and UK) by adapting it to suit characteristics for the consumption, import and production of oil. With the exception of the United States, the oil counter-shock has a substantial positive impact that is relatively similar for all the countries, with Spain benefitting just a little more because of its higher oil intensity. Ultimately, considering the past and projected changes in oil prices (at constant exchange rates), the additional growth expected on average in the major euro zone countries would be 0.6 GDP point in 2015 and 0.1 point in 2016. In the US, the positive impact would be partially offset by the crisis that is hitting the unconventional oil production business[1]. The impact on GDP would be positive in 2015 (+0.3 point) and negative in 2016 (-0.2 point). While lower oil prices are having a positive impact on global economic growth, this is unfortunately not the case for the environment …

[1] See the post, The US economy at a standstill in Q1 2015 : the impact of shale oil, by Aurélien Saussay, from 29 April on the OFCE site.