The potential headache of measuring economies in public expenditure

By Raul Sampognaro

Since 2009, the French budget deficit has been cut by 3.3 GDP points, from 7.2 percent of GDP in 2009 to 3.9 points in 2014, even though the economic situation has been weighing heavily on the public purse. This improvement was due to the implementation of a tighter budget policy. Between 2010 and 2013, most of the consolidation effort came from higher taxes, but since 2014 the effort has largely involved savings in public expenditure. In 2014, public expenditure excluding tax credits[1] recorded its weakest growth since 1959, the year when INSEE began to publish the national accounts: in value, spending excluding tax credits increased by 0.9%, though only 0.3% in volume terms (deflated by the GDP deflator).

At first glance it may seem counter-intuitive to talk about savings on spending even though the latter has been rising constantly. This rise is, however, well below potential growth, which reflects a real long-term effort to reduce the ratio of spending to GDP. Indeed, the formula usually used to calculate the effort on spending depends on the hypothesis adopted on potential growth:

To understand why the extent of the effort on public expenditure is dependent on potential growth, one must understand the underlying concept of the sustainability of the debt. There is a consensus on the theoretical definition of the sustainability of the public debt: it is sustainable if the current stock of debt could be repaid by the anticipated future stream of the State’s net revenues[2]. While the concept is clear, its practical application is more difficult. In practice, fiscal policy is deemed sustainable when it makes it possible to stabilize the ratio of public debt to GDP at a level deemed consistent with maintaining refinancing by the market.

Thus, changes in spending that are in line with that goal should make it possible to stabilize the share of public expenditure to GDP over the long term. However, as public spending essentially responds to social needs that are independent of the economic situation (apart from certain social benefits such as unemployment insurance), stabilizing its share in GDP at any given time (which would imply it changes in line with GDP) is neither assured nor desirable. In order to deal with this, changes in the value of public expenditure are compared to the nominal growth rate of potential GDP[3] (which depends on the potential growth rate and the annual change in the GDP deflator).

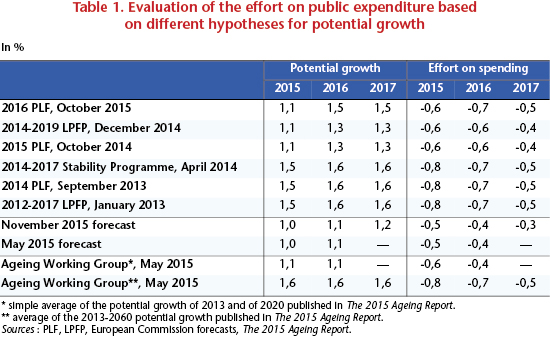

An increase in expenditure that is above (respectively below) the potential reflects a positive (negative) impulse, because in the long run it leads to an increase (decrease) in the ratio of public spending to GDP. While the application of this concept may seem easy, potential growth is unobservable and uncertain because it is highly dependent on the assumptions made about demographic variables and future changes in productivity. In the 2016 Budget Bill (PLF), the government revised its potential growth assumptions for the years 2016 and 2017 upwards (to 1.5% instead of 1.3% as adopted at the time of the vote on the LPFP supplementary budget bill in December 2014).

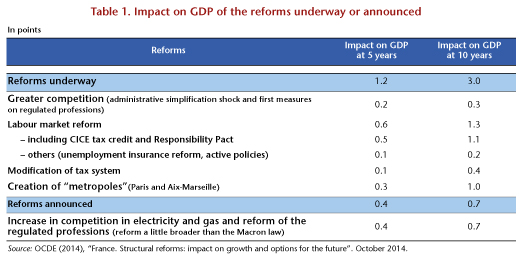

This revision was justified on the basis of taking into account the structural reforms underway, in particular during the vote on the Macron Act. This was the second revision of potential since April 2014 when it was estimated at 1.6% (2014-2017 Stability Programme). The government is not the only one to repeatedly revise its assessments of potential growth. When the European Commission published its latest projections[4], it revised its assessment of potential growth even though its previous assessment had been issued only in May[5]. It is not easy to see what new information could change its assessment now. These recurring revisions generally complicate the economic debate[6] and cloud discussion of the budget.

Hence using identical sets of hypotheses about the public finances, a measurement of savings on spending, and thus of the structural adjustment, would depend on the potential growth adopted (Table). Assuming a value for the growth in public spending (excluding tax credits) of +1.3% in 2016 and in 2017, the scale of the effort on spending was evaluated at 0.7 GDP point in October 2015 (using the hypotheses in the 2016 PLF) but 0.6 point in December 2014 (2014-2019 LPFP).

While the differences identified above may seem small, they can have significant consequences on the implementation of fiscal rules, which can lead the various players to act on their assumptions in order to change the effort shown [7]. Even though this notion should guide the vision of the future trajectory of Europe’s economies, the debate winds up being hijacked. Recurrent revisions in potential growth focus discussion on the more technical aspects, even though the method of estimating potential growth is uncertain by definition and there is not even a consensus among economists. Thus, the European Semester, which should set the framework for discussion and coordination between Member States in determining the economic policy that best suits the macroeconomic context, for France and for the euro zone as a whole, gets lost amidst technical discussions that are of no particular interest.

[1] Reimbursable tax credits – essentially the CICE and the CIR credits – are recognized in public expenditure on the basis of the 2010 national accounts. In order to remain closely in line with economic concepts, public spending will be analyzed excluding tax credits, which will be considered as a component of taxation.

[2] This definition is accepted both by the academic literature (see for example, D’Erasmo P., Mendoza E. and Zhang J., 2015, “What is a Sustainable Public Debt?”, NBER WP, no 21574, September 2015, and by international organizations (see IMF, 2012, “Assessing Sustainability”).

[3] It can also be compared to an underlying trend in public expenditure which itself takes into account the changing needs to which spending responds.

[4] The European Commission expects France to grow by 1.1% in 2015, 1.4% in 2016 and 1.7% in 2017.

[5] The evaluation has changed to the second decimal.

[6] For this debate, see H. Sterdyniak, 2015, “Faut-il encore utiliser le concept de croissance potentielle?” [Should the concept of potential growth still be used?], Revue de l’OFCE, no. 142, October 2015.

[7] The revisions of potential growth may have an impact on the implementation of procedures. These revisions cannot give rise to penalties. At the sanctions stage, the European Commission’s hypothesis on potential growth, made at the recommendation of the Council, is used in the discussion. However, it is likely that a difference of opinion on an unobservable variable could generate friction in the process, reducing the likelihood of sanctions and making the rules less credible.