Poverty and social exclusion in Europe: where are things at?

In March 2010, the EU set itself the target for the year 2020 of reducing the number of people living below the poverty line or in social exclusion by 20 million compared with 2008, i.e. a target of 97.5 million “poor” people in 2020. Unfortunately, due to the crisis, this goal will not be reached. The latest available figures show that in 2013 the EU had 122.6 million people living in poverty or social exclusion. Surprisingly, the EU’s inability to meet the target set by the Europe 2020 initiative is due mainly to the EU-15 countries, the so-called “advanced” countries in terms of their economic development [1]. Indeed, if the trends observed over the last ten years continue, the Central and East European countries (CEEC) will continue to experience a decline in the number of people living below the poverty line or in social exclusion. How is it that the countries of the EU-15 are performing so poorly in the fight against poverty and social exclusion? It is important to keep in mind that the East and Central European countries also perform better when we consider other indicators of income inequality within a country (e.g. the Gini coefficient, the ratio of the income of the 20% richest over that of the 20% poorest). The EU-15’s performance is troubling not only with regard to relative poverty and social exclusion, but also in terms of all the statistics concerning living conditions and income inequality.

Risk of poverty and social exclusion: what exactly are we talking about?

In order to reduce poverty and social exclusion, the Europe 2020 initiative focuses on three types of groups: people at risk of poverty, people facing severe material deprivation, and people with a low work intensity[2]. A person belonging to several different groups is counted only once.

According to Europe 2020, people are at risk of poverty when their disposable income falls below 60% of the median income observed at the national level, the median income being the level of income at which half the country’s population has a higher income and half a lower one. Since the median income threshold is calculated nationally, this means for example that a Romanian individual at the threshold of the median income has an income well below that of a French person earning the median income: the Romanian median income is in fact one-fifth the French median income in terms of purchasing power parity, that is to say, when we take into account the price differences between the countries[3]. The indicator of the poverty risk used by Europe 2020 is thus a measure of income inequality between individuals within a country, not between countries.

Note that disposable income is considered in adult equivalents, i.e. incomes were first recorded at the household level and then weights were assigned to each member (1 for the first adult; 0 5 for the second and each person over age 14; and 0.3 for children under age 14). Also note that the disposable incomes in question here are after social transfers, i.e. after taking account of allowances, benefits and pensions – that is, they are after any action by the country’s social system. In addition, the level used to define the threshold for the risk of poverty (i.e. 60% of median income) aims to take into account situations other than extreme poverty: the goal is also to take account of people who are having difficulty meeting their basic needs. For example, the poverty threshold of 60% of median income in France was 12,569 euros per year in 2013 (or 1047 euros a month). The concept of material deprivation is used to refine the definition of unmet basic needs.

People experiencing severe material deprivation are those whose lives are constrained by a lack of resources and who face at least four out of the following nine material deprivations: an inability 1) to pay the rent or utility bills (water, gas, electricity, telephone); 2) to heat the dwelling adequately; 3) to meet unexpected expenses; 4) to eat a daily portion of protein (meat, fish or equivalent); 5) to afford a week’s holiday away from home; 6) to own a car; 7) to have a washing machine; 8) to have a color TV; or 9) to have a telephone.

People living in a household with a low work intensity are those aged 0 to 59 who live in a home where the adults (aged 18 to 59) worked less than 20% of their potential capacity in the last year.

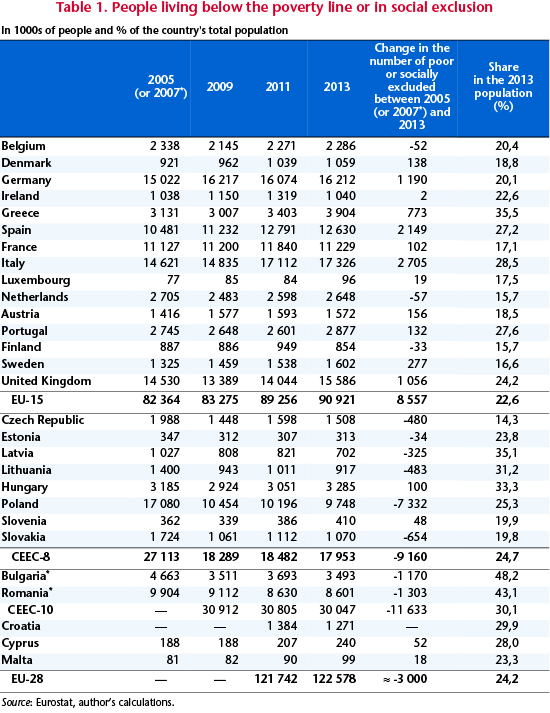

According to the latest available statistics (Table 1), 122.6 million people in the EU-28 belonged to at least one of these three groups in 2013, i.e. nearly one person out of every four (slightly more than 24%).

Contrasting developments between the EU-15 and the CEE countries with regard to poverty and social exclusion

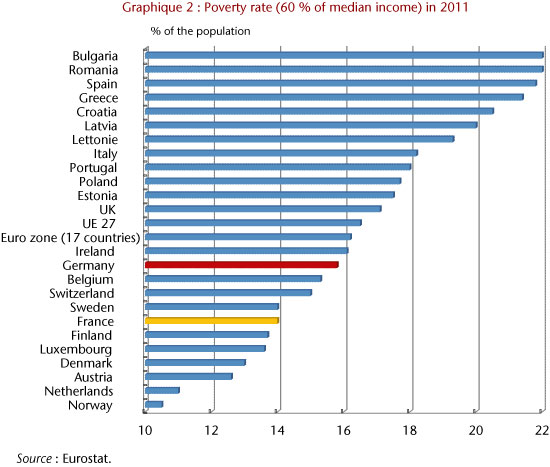

While a little over 30% of the CEE population lives in poverty or social exclusion (versus 22.6% in the EU-15), what is striking is that the number of poor and socially excluded has been decreasing in the CEE countries over the last 10 years while it has been increasing in the EU-15, especially since the onset of the crisis (Table 1).

Over the past decade, the number of people living in poverty or social exclusion fell in almost all the CEE countries (with the exception of Hungary and Slovenia) and rose in almost all the EU-15 countries (with the exception of Belgium, the Netherlands and Finland). During these 10 years, the CEE countries experienced a decline of 11.5 million in the ranks of the poor and socially excluded, while the EU-15 recorded an increase of 8.5 million, i.e. an 85% rise since 2009. The crisis has clearly hit the EU-15 hard in terms of poverty and social exclusion. The CEE countries have, all things considered, proved fairly resilient: a number of them are even continuing to see a decrease in the number of poor and socially excluded.

What’s behind these contrasting trends in poverty and social exclusion?

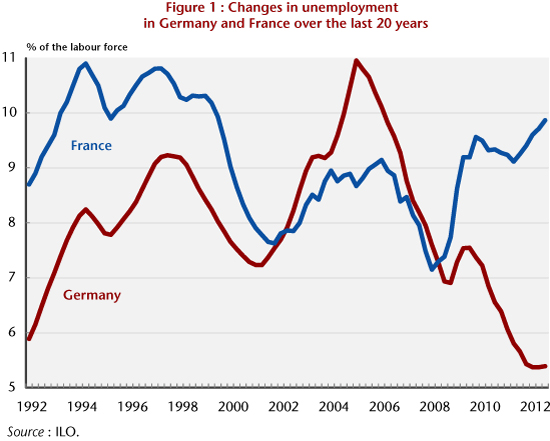

The main factor explaining the contrasting trends in poverty between the EU-15 and the CEE countries is that the economic situation has generally developed more favourably in East Europe than in West Europe, including during the crisis period.

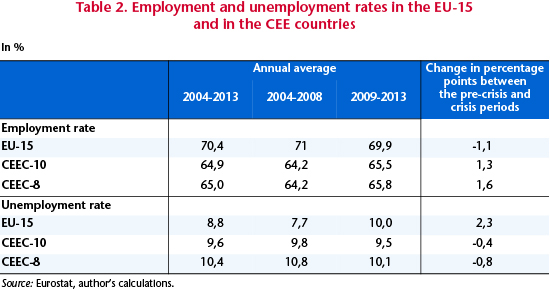

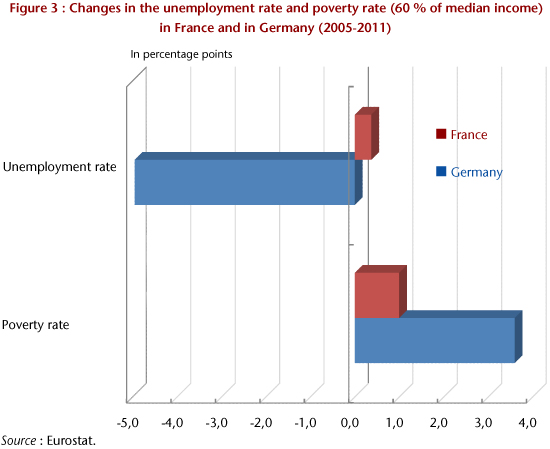

Indeed, the average GDP growth rate over the last ten years (2004 to 2013) was 3.2% in the CEEC, compared with 0.8% in the EU-15. The CEE countries, though hit by the crisis, nevertheless recorded average annual growth of 0.7% in 2009-2013 (against 0.1% in the EU-15). Likewise, the unemployment and employment rates during the crisis reflected a more favourable situation on the CEE labour markets than on the EU-15 markets (Table 2).

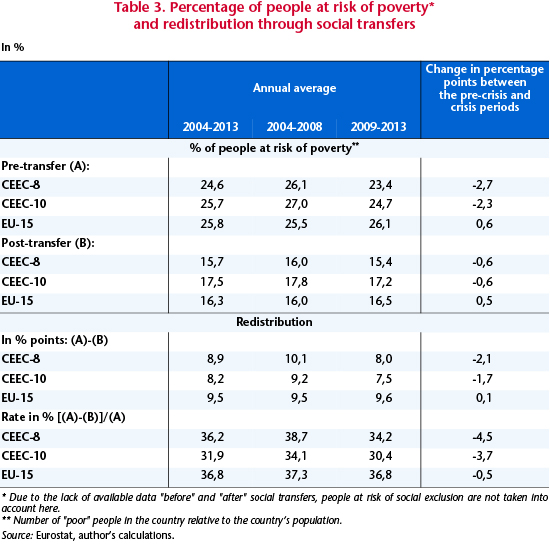

The risk of poverty prior to social transfers continued to fall in the CEE countries, while from 2009 it rose in the EU-15 (Table 3). Consequently, the share of people in the CEE countries living below the poverty line (out of each country’s total population) before transfers has fallen below the level observed in the EU-15. The crisis has thus had a direct differentiated effect (i.e. before redistribution) on income inequality within countries: in Europe’s East, income inequality has fallen, while in the West it has risen.

The workings of the social security systems in the EU-15 countries have, however, resulted in reversing (or mitigating) the differences in post-transfer poverty rates (Table 3). In 2013, the post-transfer poverty rate was 16.5% in the EU-15, compared with 17.2% in the CEE countries (15.4% excluding Bulgaria and Romania). The Gini coefficient, which is a more common measure of within-country income inequality, also confirms that income inequality is now higher in the EU-15 than in the CEEC[4].

Note that during the crisis the intensity of the redistribution (in % points or rates) was higher in the EU-15 than in the CEEC. However, over time the redistribution rate fell in both the East and the West, starting in 2009. Prior to the crisis, the social security systems in the EU-15 resulted in a 37.3% reduction in the number of people living in poverty and social exclusion; during the crisis, the rate fell to 36.8%. In the CEE countries, the fall in the redistribution rate was even greater, on the order of 3.7 percentage points. By way of illustration, if the redistribution rate for the pre-crisis period had been maintained during the crisis period, an additional 1.4 million people would have avoided the risk of poverty during the crisis (0.5 million in the EU-15 and 0.9 million in the CEEC).

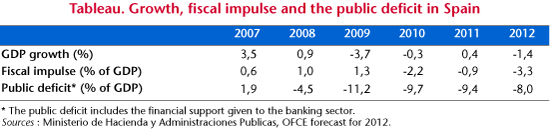

This brings us to the second explanatory factor. Are the austerity programmes being implemented in many EU countries to comply with the Stability and Growth Pact and / or to satisfy the financial markets responsible for the post-transfer increase in the number of people at risk of poverty that has taken place in the EU-15? And have these programmes acted to hold back the decline in poverty rates observed in the CEE countries, which otherwise would have been even greater?

The empirical literature on this issue is clear-cut: it shows that income inequality within countries increases during periods of fiscal consolidation[5] (Agnello and Sousa, 2012; Ball et al., 2013; Mulas-Granados, 2003; Woo et al., 2013). Among the tools of fiscal consolidation (i.e. cuts in public spending, increases in tax revenues), it is the spending cuts in particular that increase income inequality (Agnello and Sousa, 2012; Ball et al., 2013; Bastagli et al., 2012; Woo et al., 2013). Austerity programmes implemented after the onset of a banking crisis have a much greater negative effect on income inequality than programmes implemented when not in a banking crisis (Agnello and Sousa, 2012). Furthermore, small consolidations (i.e. involving a cut in the public deficit of less than 1 GDP point) have a bigger negative effect on inequality than large fiscal consolidations (Agnello and Sousa, 2012).

If the results of this (still sparse) literature are accepted, the timing of the fiscal consolidation implemented in recent years has not been ideal: the programmes have been introduced too early with respect to the occurrence of the crisis. Nor have they been optimal in size: they are insufficient to cut the deficit substantially but very costly in terms of increasing income inequality between individuals. While it is difficult to form a firm and final opinion on the link between fiscal consolidation and income inequality (and poverty) based on the sparse literature, the afore-mentioned studies do have a value: they raise questions about the potentially harmful impacts of the austerity policies that have been implemented in recent years.

[1] The Europe 2020 initiative sets out poverty reduction and social exclusion targets for each country. Here we are basically interested in the different trends between the two areas: the EU-15 and the CEE countries.

[2] See the article by Maître, Nolan and Whelan (2014) for a critical in-depth analysis of the statistical criteria for poverty and social exclusion.

[3] In current euros, the difference in income would be even greater: in 2013, the French median income was 20,949 euros a year, and Romania’s 2071 euros, so Romania’s median income per year would thus be one-tenth, not one-fifth, of the French level.

[4] The difference (in favour of the CEE countries) is even more pronounced due to the exclusion of Bulgaria and Romania: the Gini coefficient after transfers is then 0.291 against 0.306 for the EU-15. The Gini coefficient can take a value between 0 and 1. As the coefficient approaches 1, an increasingly small share of the population has a larger and larger share of total income. Ultimately, when the coefficient reaches 1, a single individual has all the income.

[5] Because of the way the poverty line is calculated (i.e. 60% of median income), an increase in the share of people living below the poverty line definitely corresponds to an increase in income inequality between individuals.