Redistributive policies and the demand for fairness

par Gilles Le Garrec

Six years after the onset of the Great Recession, France’s economic situation is still gloomy: growth is sluggish, there are almost 3.5 million unemployed in mainland France, and the public debt is approaching the threshold of 100% of GDP (95.4% according to the 2014 Maastricht criteria according to the OFCE). One cause for satisfaction has been the ability of the social protection system to mitigate the increase in income inequality. The Gini index [1] calculated on the labour force (population age 18 to 65) shows that, between 2008 and 2011, inequality in market income increased by 2.9 percentage points while inequality in disposable income increased by only 1.8 points. To achieve this, social spending rose by 0.8 point, bringing it to 19% of GDP excluding old-age pension expenditures [2]. However, one of the fears associated with the crisis (due to its duration and magnitude) is that France can no longer afford to provide people with such a high level of social protection. Is this fear justified? Not necessarily.

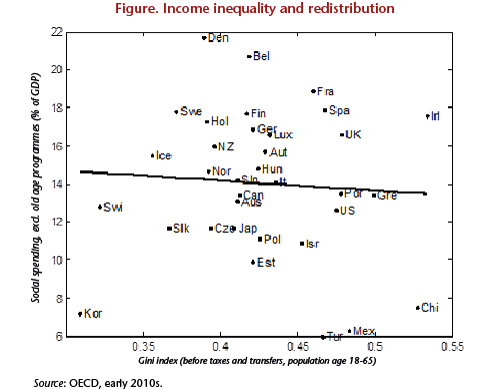

Starting from the premise that in a democracy a policy can be carried out only if it has the majority support of its citizens, Meltzer and Richard (1981) suggest that increasing inequality leads to an increasing demand for redistribution, not because people have an aversion to inequality, but rather because they are motivated by their own interests. Therefore the poorer the median individual becomes in terms of income [3] compared to the average population, i.e. as the income distribution becomes more unequal, the greater will be that individual’s interest in income redistribution. In this perspective, the increasing inequality generated by the economic crisis should result in an increase in social spending. Redistribution is thus not inflicted, but instead should have the support of a majority of the citizens. Though attractive in its simplicity, this explanation suffers from a major flaw: the data does not show any positive correlation between income inequality and redistribution. Typically, the level of inequality measured by the Gini index (before taxes and transfers) is 0.46 in France with respect to the labour force, versus 0.475 in the US, where the level of social spending is only 13% of GDP[4]. More generally, and as is illustrated in Figure 1, this presumed correlation proves to be zero or even negative (see Perotti 1996 for an empirical review). To understand the possible weaknesses of the French social protection system, the analytical framework proposed by Meltzer and Richard (1981) will not be sufficient.

This discrepancy between the observed facts and the theory has spawned several lines of research[5]. In particular, the assumption that individuals are motivated solely by self-interest has been challenged by a large number of laboratory experiments. Take, for example, the ultimatum game. In this game, two anonymous subjects must agree on how to divide a sum of money. The first participant must make an offer to share the sum. The second can then either accept or reject the offer. If he accepts, then the two share, otherwise neither gets anything. In theory, the first player, knowing that any positive offer will be accepted, should always offer the second player as little as possible. Contrary to this prediction, the results of the experiment show that many people offer 50% of the total to the second player, with an average offer of around 40%. Furthermore, any offer of less than 25% of the total has a high chance of being rejected. These results demonstrate behaviours characterized by a sense of distributive justice. When people are asked outside the laboratory setting about the reasons why someone would favour redistribution, this is the particular reasoning given. Survey data also underscore that individuals tend to give greater support to redistribution when they think that poverty is caused by factors for which the victims are not responsible (see Fong, 2001). In line with these results, the belief that luck rather than effort determines income proves to be a better predictor than income inequality of how much redistribution takes place in a country.

Thus, in order to determine the ways in which concern for others can explain the differences in redistribution observed between democracies, the theoretical literature has focused on the formation of beliefs. In the approach of Alesina and Angeletos (2005), individual preferences combine personal interest and the demand for fairness. Specifically, fairness is defined according to the principle that each person should get what they deserve. Knowing that income depends on both luck and the effort exerted, the authors argue that the differences between the amounts redistributed in different countries result from different self-fulfilling beliefs. Americans, expecting little redistribution, invest more in their human capital and thus create the conditions for a low level of redistribution because the role of chance is reduced in the determination of income. Conversely, Europeans, expecting strong redistribution, invest less in their human capital. Luck is thus more important in the determination of income; individuals will therefore support strong redistribution in accordance with the principle of fairness. Furthermore, assuming that Americans and Europeans share the same preferences, Alesina and Angeletos highlight an important result: the low-redistribution American model is preferred by a majority of citizens over the European model because it produces less distortion and thus results in a higher overall income. However, this does not mean that poor people do not prefer the model with strong redistribution.

In contrast to this result which is based on the assumption that Americans and Europeans share identical preferences, Corneo (2001) showed that West Germans incorporated collective motivations into their preferences, whereas Americans were motivated only by their own interests. The intensity of a collective motivation is thus culturally determined.

In this context, building on the approach proposed by Alesina and Angeletos (2005), Le Garrec (2014) has offered a mechanism for the cultural transmission of the intensity of the demand for fairness. In accordance with the socialization process, a person’s observation during childhood of the previous generation’s inability to develop a fair redistribution policy will reduce the moral cost to that person of not supporting a fair policy later in life. When someone is socialized in an environment characterized by a fair redistributive policy, the demand for fairness remains strong in the person’s preferences: a system with strong redistribution (as in France) is perennial and perpetuated from generation to generation. Conversely, if people are socialized in an environment where the redistributive decisions deviate significantly from distributive justice, the internalization of the norm “individual success comes first” reduces the weight of the moral imperative in their preferences. In this case, a system with little redistribution (as in the US) is also sustainable. In Le Garrec (2014), the choice of a system will therefore depend on the respective histories of the nations[6].

In light of the way the canonical model of Meltzer and Richard (1981) has been extended, based on the demand for fairness observed at the individual level, can we understand the concerns expressed about the future of the French social welfare model, that is to say, a model characterized by strong redistribution? First note that in the later developments of the model, since individuals are motivated in part by their own interests, the Meltzer-Richard effect continues to exist. Rising inequality tends to increase the level of redistribution, and this receives majority support in both Europe and the United States. However, based on the Alesina-Angeletos approach, the depth of the economic crisis could weaken the French model if it leads people to believe that it can no longer be financed. In this situation, the belief could become self-fulfilling and eventually lead to a sharp reduction in the generosity of the welfare system, with a shift towards a US-style system. This interpretation of the Alesina-Angeletos model (2005) is all the more credible as the low-distribution American model seems to be preferred by most Europeans. The exposure that could result from the crisis could then serve to change beliefs. This perspective, however, is not present in Le Garrec (2014), and rightfully so as preferences co-evolve with the social protection system. A French person will (on average) prefer strong redistribution because his or her preferences express a strong demand for fairness. From this point of view, the high redistribution model, like the low redistribution one, seems very durable. Nevertheless, in Le Garrec (2014) the sustainability of the high redistribution model requires a minimum consensus in society on the causes of injustice in order to ensure a moral standard that is relatively strong. However, the economic crisis in Europe is characterized precisely by strong disagreement about its origins: excessive debt on the part of households or government, fiscal austerity, monetary conservatism, divergence in competitiveness with a single currency, a lack of solidarity among nations, etc. From this perspective, the crisis could jeopardize the French model by weakening moral standards. Ultimately, in contrast to the approach of Meltzer and Richard (1981), the approaches of Alesina and Angeletos (2005) and Le Garrec (2014), which go more deeply into people’s motivations, offer keys to a different and complementary understanding of the potential dangers that could face the French social security system as a result of the economic crisis.

References

Acemoglu D., Naidu S., Restrepo P. and Robinson J. (2013), Democracy, redistribution and inequality, NBER WP 19746.

Alesina A. and Glaeser E. (2004), Fighting poverty in the US and Europe: A world of difference, Oxford University Press.

Alesina A. and Angeletos G.-M. (2005), Fairness and redistribution: US versus Europe, American Economic Review, 95(4), pp. 960-980.

Corneo G. (2001), Inequality and the State: Comparing US and German preferences, Annals of Economics and Statistics, 63/64, pp. 283-296.

Fong C. (2001), Social preferences, self-interest, and the demand for redistribution, Journal of Public Economics, 82(2), pp. 225-246.

Le Garrec (2014), Fairness, socialization and the cultural demand for redistribution, OFCE WP 2014-20.

Meltzer A. and Richard S. (1981), A rational theory of the size of government, Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), pp 914-927.

Perotti R. (1996), Growth, income distribution and democracy: what the data say, Journal of Economic Growth, 1(2), pp. 149-187.

[1] The Gini index is based on a comparison between proportions of the population and their combined income. A value of 0 represents perfect equality, a value of 1 complete inequality.

[2] As the pension system is not aimed at reducing income inequality, but at providing deferred wages on the basis of what has been paid in, it is best to remove these expenditures in order to properly assess the capacity of social spending to reduce these inequalities.

[3] 50% of individuals have an income that is higher than this person’s, and 50% lower.

[4] Social spending (and taxation) is also less progressive in the United States than in France. Thus, social spending of 1% of GDP would reduce the Gini index by 1.74% in France compared with 1.46% in the United States.

[5] See Alesina and Glaeser (2004) and Acemoglu et al. (2013) for an overview of the various extensions made to the canonical model.

[6] It is beyond the scope of this note to analyze the historical facts that would help explain the convergence towards one type of social protection model rather than another. For this, please refer to the work of Alesina and Glaeser (2004).