Some reflections on the ECB’s Comprehensive Assessment

Mauro Napoletano[1] and Stefano Battiston[2]

(Ce texte n’est pas publié en français)

The European Central Bank (ECB) officially released the results of its Comprehensive Assessments of euro area banks on October 26th, thus making a very important step towards the creation of the European Banking Union. The ECB exercise unveiled the global robustness of the euro area banking sector despite the bumpy week financial markets had after its release. On the one hand, most banks hit by important financial shocks and affected by privately and publicly funded re-capitalization efforts (as in Spain) passed the stress test hurdle. On the other hand, fragilities were identified only in few countries (notably Italy, Greece and Portugal) and were basically the result of balance-sheet problems in some big institutes therein (e.g. Monte dei Paschi di Siena in Italy). One may nonetheless wonder whether the above picture of global stability, emerging from the results of the ECB assessment, is well-founded, and whether the methods used by the ECB, and the consequent re-capitalization efforts required, will be sufficient to insulate the Euro Area financial systems from financial meltdowns like the one of 2008/2009.

To shed more light on such issues it is important to remark that the Comprehensive Assessment is articulated into two blocks[3]. The first one, the stress test on banks, amounts to a check of the robustness of bank’s balance sheets in adverse scenarios provoked by financial and real shocks of different nature. The second one is the so-called “Asset Quality Review” (AQR) and corresponds to a point-in-time evaluation of the assets portfolio of Euro Area banks with the goal of identifying problematic assets. The AQR constitutes a great innovation of 2014 assessment with respect to similar ones carried out in 2010 and 2011, which did not feature a detailed evaluation of banks’ asset book. Performing such a comprehensive evaluation has two clear advantages. First, it is a big step towards improving the overall transparency of the financial system. Second, and relatedly, it helps regulating authorities to get important details about the degree of complexity of the asset side of banks, which has played a key role in the unfolding of the financial crisis of 2008/2009. The Euro-Area comprehensive AQR is not the only positive aspect of the current assessment. Other welcomed novelties are represented by the higher coverage of the current assessment (130 banks) with respect to the sample of banks considered in the 2010 and 2011 stress tests[4] (respectively 91 and 90 banks). Moreover, the scope of macro-shocks and country-specific shocks considered in the stress tests was broader. More in detail, the ECB considered four different types of adverse financial and real shocks that could threaten banks stability: a) an increase in global bond yields; b) a deterioration of credit quality; c) a stalling of policy reforms; d) a lack of necessary balance-sheet repair to maintain affordable market funding. Finally, the 2014 assessment has been based on a unified methodology, which has limited the discretional interpretation of rules by national authorities and by banks.

The ECB assessment constitutes an important step towards a better monitoring of euro area financial stability. At the same time, the structure and the methods used by the ECB lead one to raise more than one concern the overall stability picture that emerges out of it. Recent accounts of the ECB’s exercise stress that the ECB assessment has partially accounted for some important banking risks, like for instance liquidity risk (the risk of not being able to honor payments). In addition, results of the AQR and the stress tests were conducted in parallel. Accordingly, results from the evaluation of the quality of banks asset books were not used to test the stability of the bank themselves. Last but not least the ECB performed the assessment using a bottom-up approach, i.e. relying on the information provided by banks and national regulators. The latter were in close contact with banks in their country to check the validity of the information. This governance structure of the assessment poses some problems, as national regulators may have the incentive not to disclose relevant information that would reveal the extent of the capital shortfall in their countries.

However, the main weakness of the ECB assessment as a banks’ financial robustness exercise probably lies in the failure to consider one fundamental property of current financial systems (Euro-Area one included), namely its interconnectedness. Indeed, the financial system is structured as a complex web of financial relationships of very different nature (e.g. unsecured lending, repurchasing agreements, derivatives) and among different types of actors (e.g. banks, hedge funds, money market, pension funds).

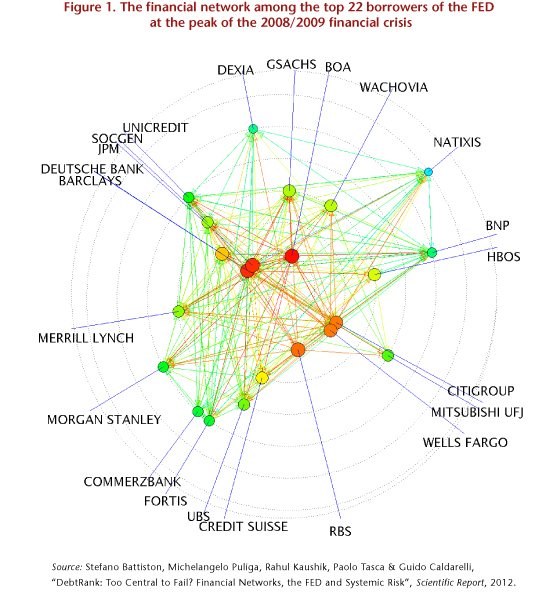

There is a growing consensus around the idea that financial interlinkages play an important role in the emergence of financial instabilities. Their role is also acknowledged by the Basel Committee on banking supervision that uses interconnectedness as one of the dimensions to determine the list of Globally Systemic Financial Institutions (G-SIBs). Figure 1 provides a visual idea of an empirically-observed network of financial inter-linkages across some major banks. Links appearing in the figure show the estimated impact of a bank on the balance sheet of another one and were estimated at the peak of the 2008/2009 financial crisis (March 2009, i.e. the period of minimum market capitalization of banks) by using the “Debt-Rank” method developed in Battiston et al. (2012). In the figure higher systemic importance is identified by the color of the node by a more central location of the node. In other words, banks colored in red (rather than in yellow or in green) and closer to the center are also the banks that are systemically more important, in the sense that the default of one of them would have larger impact on other institutions in the financial system.

One main reason why financial linkages matter for financial instability is that they can have ambiguous effects on the risk exposure of banks: on the one hand, they increase individual profitability and reduce individual risk, but on the other hand, they may generate important external effects (e.g. my insolvency can become yours if it causes a significant drop in the value of your assets), thus increasing systemic risk. On this topic several issues remain open but much work has already been done in recent years and two main “transmission channels” have been emphasized. First, shocks move from a bank to another via the direct interlocks between balance sheets. That is, since the liabilities of one bank are the assets of some other banks, the default of the debtor may imply a loss for the creditors. Likewise, in case creditors decide to hoard liquidity rather than providing it to other market players, this has negative external effects to other institutions as it can reduce the liquidity accruals of the latters and the overall liquidity in financial markets. Second, there are indirect connections among banks due to the fact that they invest in common assets. This implies that, for instance, if as a result of a shock on the price of an asset, a bank sells a quantity of that asset sufficient to move down the price, the other banks holding the same asset will experience both the initial shock and the secondary shock and may start in turn to sell the asset themselves, triggering a devaluation spiral.

Embedding the above described channels of financial contagion and distress is thus fundamental for a proper evaluation of the stability of banks in the euro area financial system, and for the stability of the system as a whole. Indeed, interconnectedness implies that the stability of one bank cannot be assessed independently from the stability of other banks in the system. It also implies that the stability of the financial system as a whole cannot be reduced to the sheer sum of the stability of the single banks composing it. The AQR uses the Basel Committee’s G-SIBs list (which does account for interconnectedness) to classify banks in the euro-area. However, the notion interconnectedness is not used, neither in the evaluation stage of the AQR nor in the stress test.

To sum up, the ECB assessment is a key step towards the creation of a banking union in the Euro Area. At the same time, it is important that financial network aspects are taken into serious consideration, to get better measures of the possible financial fragilities of banks and of the necessary actions to tame them. Some stress tests methodologies accounting for the complex features and consequences of financial inter-linkages are already available (see e.g. the discussion in Staffen, 2014, and the works of Markose et al., 2012 and Battiston et al., 2012). It is also likely that the new data resulting from the ECB’s AQR will foster future research on these new stress test methodologies and bring some of their hints in the future assessments of the euro area banking sector.

[1] OFCE, Skema Business School, Sophia-Antipolis (France), and Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa (Italy). E-mail address: mauro.napoletano@sciencespo.fr

[2] Department of Banking and Finance, University of Zürich. E-mail address: stefano.battiston@uzh.ch

[3] The ECB has conducted a comprehensive assessment of 130 banks in the euro area. The AQR was undertaken by the ECB and national competent authorities (NCAs), and was based on a uniform methodology and harmonized definitions. The stress test was undertaken by the participating banks, the ECB, and NCAs, in cooperation with the European Banking Authority (EBA), which also designed the methodology along with the ECB and the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB). See the ECB comprehensive assessment aggregate report for more details.

[4] The 2010 and 2011 stress tests exercises were EU-wide and conducted by the EBA in collaboration with national supervisory authorities.