Is France’s trade deficit entirely structural?

By Eric Heyer

The issue at the heart of the debate between those arguing that a lack of supply is behind the low level of activity in France over the last four years and those arguing that the problem is a lack of demand is the nature of the country’s trade deficit.

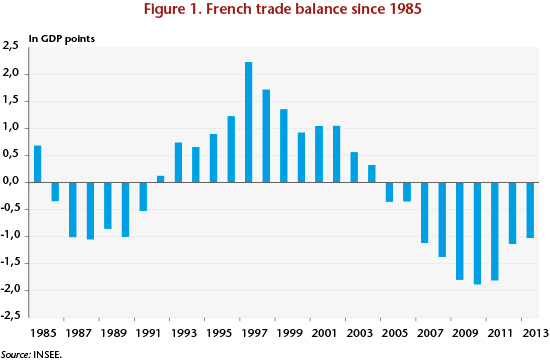

On the one hand, the French economy has a number of symptoms characteristic of an economy experiencing a shortfall in demand: strong disinflation, high unemployment, businesses declaring substantial spare capacity due mainly to a lack of demand, etc. But, on the other hand, the existence of a persistent deficit in the trade balance (Figure 1) casts doubt on the competitiveness of French firms and on their capacity to meet additional demand, which would thus express a problem with supply.

So, after more than ten years of trade surpluses, which represented over 2 GDP points in 1997, France’s trade balance turned negative in 2005. After widening gradually until 2010 when the deficit reached nearly 2 GDP points, the trend turned around. In 2013 (the latest available figure), the trade deficit still stood at 1 GDP point.

This observation is not however sufficient to dismiss all the arguments of the proponents of a demand shortage that France simply suffers from a supply problem. What is needed at a minimum is to analyze the nature of the deficit and try to separate its structural component from its cyclical component. The latter is the result of a difference in the economic cycle between France and its major trading partners. When a country’s situation is more favourable than that of its partners, that country will tend to run a deficit in its trade balance linked to domestic demand and thus to more buoyant imports. A trade deficit may thus arise regardless of how competitive the country’s domestic firms are.

One way to take this cyclical gap into account is to compare the gaps between an economy’s actual output and its potential output (the output gap). At the national level, a positive output gap (respectively negative) means that the economy is in a phase of expansion (respectively of contraction) of the cycle, which, other things being equal, should lead to a cyclical deterioration (or improvement) in its trade balance. In terms of the trading partners, when they are in a cyclical expansionary phase (positive output gap), this should lead to a cyclical improvement in the trade balance of the country in question.

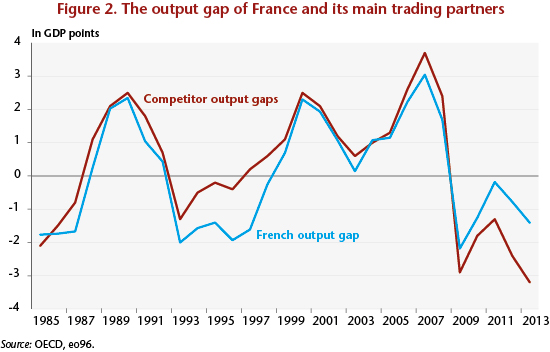

Using data from the latest issue of the OECD’s Economic Outlook (eo96), we calculated an “aggregate” output gap for France’s partners by weighting the output gap of each partner by the weight of French exports to that country in France’s total exports.

This calculation, shown in Figure 2, highlights two points:

- The first is that, according to the OECD, France’s output gap has been negative since 2008, signalling the existence of room for the French economy to rebound.

- The second is that the economic situation of our trading partners is even worse. The cyclical gap, measured by the difference between the output gaps of France and of its partners, indicates a significant difference in favour of France.

It is then possible to assess the impact of the cyclical situation of the country and that of its main partners on the trade balance.

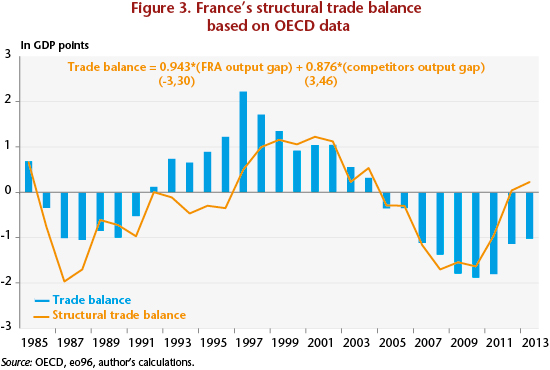

A simple estimate using Ordinary Least Squares over the period 1985-2013 shows a relationship of cointegration between these three variables (trade balance, output gap of France and output gap of its partners) for France. The signs obtained are consistent with what we would intuitively expect: when France is in an expansionary phase, its trade balance tends to worsen (coefficient of -0.943). In contrast, when rival countries are experiencing a boom, this makes for an improvement in France’s trade balance (coefficient of +0.876).

France’s structural trade balance since 1985 can then be calculated by subtracting the cyclical effect (national and competitors) from the observed trade balance.

Figure 3 shows this calculation. First, the fall in the euro in the late 1990s led to a structural improvement in France’s structural balance. The sharp deterioration in the trade balance between 2001 and 2007 would then be entirely structural: it would be explained in particular by China’s entry into the WTO, by the competitive disinflation policy adopted by Germany, and by the appreciation of the euro. Since the 2008 crisis, however, an increasingly substantial portion of the French trade deficit would be cyclical. So even if French growth were sluggish, the country’s economic difficulties were nonetheless less dramatic than in the case of some of its trading partners[1]. It is this relatively more favourable performance compared to its major trading partners that would have led to the rise of a trade deficit, part of which was cyclical. By 2013, the imbalances in the current account would be entirely cyclical in origin.

This result echoes the analysis provided by the French national accounting office on the factors driving growth over the last four years: the level of real GDP in the third quarter of 2014 was only 1.4% higher than in first quarter 2011. An analysis of the factors contributing to this performance is unambiguous: private demand (household and business) was down sharply (-1.6%), particularly household consumption, the traditional engine of economic growth. While there are more households today than four years ago, their total consumption was 0.6% below their 2011 level. However, while the French economy’s ability to deal with the global competitive framework is being questioned by the dominant discourse, foreign trade has in fact had a very positive impact in the last four years, with a boost from exports, which contributed a positive 2 GDP points to growth. In short, for four years the French economy has been driven mainly by exports, while it has been held back by private demand.

This analysis is of course based on an assessment of output gaps, whose measurement is tricky and subject to sharp revisions. In this respect, while there is an institutional consensus on the estimate that France has a negative output gap, there is also a broad range in the magnitudes of the room for a rebound, ranging in 2014 from 2.5 to 4 points, depending on the institution (IMF, OECD, European Commission, OFCE).

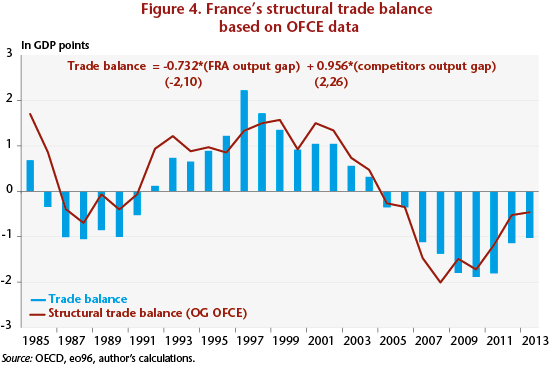

This diagnosis would be somewhat attenuated if an output gap were used for France that was more negative than the one calculated by the OECD: using the OFCE’s estimate for France (an output gap of -2.9 GDP points in 2013 instead of the OECD’s -1.4 points) and retaining the OECD measure for its partners, France’s more favourable relative performance compared to its major trading partners would now explain only half of its trade deficit[2]. Part of the deficit observed would therefore be explained by the competitiveness problems of French business (Figure 4).

In conclusion, as with any measurement of a structural variable, the evaluation of the structural trade balance is sensitive to the measure of the output gap. Nevertheless, it is clear from this brief analysis that:

- If the French economy is considered to suffer mainly from a supply problem (output gap close to zero), whereas our partners, mainly European, face a shortfall in demand (negative output gap), then the deficit in our trade balance would essentially be cyclical.

- However, if France, like its partners, is also experiencing a shortfall in demand, then only part of our deficit is cyclical, and the rest is related to a problem with the competitiveness of our companies.

This last point seems to us closer to the actual situation of the French economy. While French companies’ have undeniably lost some competitiveness, this should not be overestimated: the sluggishness that has characterized our economy for nearly four years is due not only to a lack of supply and the disappearance of the potential for growth – even if this is unfortunately likely to taper off – it is also due to a significant decline in demand.

[1] For example, Italy and Spain entered a second recession in third quarter 2014, leaving their GDP lower than its pre-crisis level by 9% and 6% respectively.

[2] We find a similar result when the previous version from the OECD (eo95) it used for France and all its partners.