By Pierre Madec and Henri Sterdyniak

On October 24th, the French Economic Analysis Council (the CAE) published a paper proposing a new policy on rental housing in France. This paper calls into question a number of government measures in the ALUR bill currently under discussion in Parliament, such as rent control and the universal rent guarantee (the GUL) [1]. Are these criticisms justified? The authors acknowledge that the housing market is very specific, that it requires regulation, and that the state needs to build social housing and assist poor families with housing. Their differences with the policy that the current government intends to follow are thus intrinsically limited, and are more related to means than ends. The free market does not work in the area of housing. There is a need for public intervention that should aim, as we shall see, at contradictory objectives, programmes whose structure is by their very nature subject to discussion.

The existing rental housing stock: co-management and moral hazard

With regard to the private rental market, the authors in essence propose the introduction of a system of housing “flexicurity”, akin to what has been recommended for the labour market: diversification and liberalization of leases, new rights for the landlord, more flexible conditions for terminating a lease, and the development of a system of co-management of the private rental market built around a “housing authority” whose powers would extend from setting “benchmark” rents to managing leases. This “authority”, which would be jointly administered by tenants and landlords, would play a mediating role in conflicts between them, much like the prud’hommes bodies for labour disputes. The main argument used by the authors to condemn a scheme such as the GUL universal rent guarantee is that it would create significant problems with moral hazard, that is to say, the guarantee would encourage those covered to take “too many risks”. In this case, tenants, who would have a guarantee that any payment defaults would be covered by the fund, would be less concerned about paying their rent; they could therefore choose housing that is more expensive than what they really need. Owners would also be less concerned in their selection of a tenant. The authors also use the argument of moral hazard to defend the establishment of flexible leases: in their opinion, this would help in the fight against the deterioration of housing as well as in disputes with neighbours. The idea of tenants who are systematically “voluntary deadbeats” ready to degrade the housing they have leased seems simplistic and over the top. However, this idea is developed at some length by the authors. They seem to forget that the GUL will in particular cover tenants who are unable to pay their rent because of financial hardship (unemployment, divorce, etc.). This guarantee above all offers new protection for the owner – protection funded equally by landlords and tenants through a pooling system. In case of failure to pay rent, the landlord will be reimbursed directly from the fund. The latter will then examine the tenant’s situation and proceed either with a mandatory collection or personalized support if the tenant is genuinely unable to pay. The GUL should allow landlords to rent to people who are in vulnerable situations (workers in precarious jobs, students from low-income families), without the latter needing to come up with deposits. Owners would have less incentive to seek safe tenants (civil servants, students from better-off families, employees of large companies). The State is fully within its role by covering a social risk that has been aggravated by the crisis and growing job insecurity. Isn’t this worth the fantasized risk of an increase in moral hazard? The matter of the lease raises a question of substance. Should encouragement be given to the development of individual landlords, which inevitably generates friction between on the one hand the owner’s concern to freely dispose of their property and be as certain as possible that the rent will be paid and on the other hand the tenant’s concern to enjoy a secure tenure and their demand for the right to housing? A household with a low or irregular income, which is thus more vulnerable, must also be able to find housing in the private sector. It may also seem preferable either to encourage institutional investors to invest in this sector or for households to make greater use of collective investment in housing and set up mechanisms such as the GUL, which can collectively address the issue of non-payment of rent. Housing is far from being an ordinary good. It is, and the authors do point this out, above all an essential need, a fundamental right. The massive casualization of housing through the establishment of a system of liberalized leases cannot be the solution. On the contrary, authors drawing on the German model, on the introduction of open-ended leases (the standard lease in Germany), constitute a major advance in terms of the tenant’s security [2].

Rent control versus the law of the market

With regard to rent control, the authors rely on a number of studies in order to demonstrate the existence of a correlation between the state of degradation of the rental stock and rent control measures. However, the ALUR law contains provisions for taking into account any renovations undertaken. There is of course a continuing risk that the stock will deteriorate, but once this has been spelled out, we should also mention the equally likely result that the stock could improve precisely due to this provision for taking renovations into account. The authors also develop the idea that control measures will lead to a significant decrease in residential mobility. While this is a real risk for programmes designed to regulate rents during the lease and not upon re-letting (the main cause of the growing inequality in rents observed in France since the 1989 Act), the rent control provisions in the ALUR law are, on the contrary, designed to lead to a convergence in rents [3]. This convergence, although modest, given the large gap still allowed (over 40%), will tend in the direction of greater mobility. In reality, the most important risk raised by the authors is that the number of dwellings available for rent might fall. Although it seems unlikely that landlords already on the market would massively withdraw their rental properties [4], rent control measures could discourage new investors in the rental market because of the resulting decline in yields. This would exacerbate the supply / demand imbalance in high-pressure areas. In practice, this seems unlikely. Even if there were a significant drop in the number of new investors, those already present on the existing market, given the lease conditions (and contrary to the authors’ expectations), cannot easily sell their property, except to a new investor who in light of the fall in yields will demand lower prices. The tax incentive schemes (Duflot type) currently in force on the market for new housing suggest that landlords who invest will be only slightly affected by rent control. Some investors may nevertheless turn their backs on the construction of new housing, which, in the short term, would tend to push down property prices [5], thus encouraging homeownership and a fall in land prices. The public sector would however have to be ready to take over from private investors. Nearly one in three households in the first income quartile (the poorest 25%) is a tenant in private housing and is subject to a median housing burden, net of housing assistance, of 33%, an increase of nearly 10 percentage points since 1996. Rent control above all offers protection for these low-income households – households that, given the stagnation in social housing and the increasing difficulty in getting on the property ladder, have no choice other than to rent housing in the private sector. As the approach proposed by the Duflot Act consists of “putting in place a rent control framework to cut down on landlords’ predatory behaviour. Not seeking to try to attract investors based on exorbitant rents and expectations of rising real estate prices” does not seem illegitimate if it is actually accompanied by an effort in favour of social housing. Pressure on the housing market (where supply and demand are rigid) has permitted high rent increases, which is leading to unjustified transfers between landlords and tenants. These transfers hurt the purchasing power of the poorest, the consumer price index, competitiveness, and more. Conversely, these increases can stimulate the construction of new housing by pushing up the value of property, but this effect is low and slow (given the constraints on land). Rent control can help put a stop to rent increases, even if it undermines incentives for private investment in housing to some extent. It cannot be excluded a priori.

Social housing mistreated

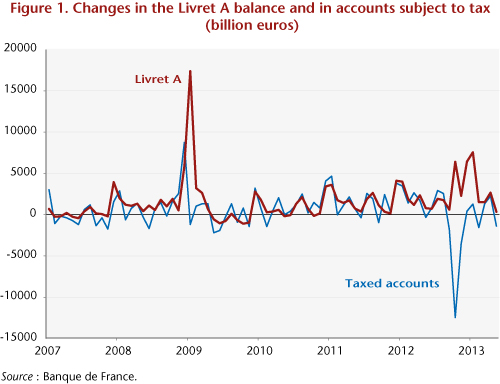

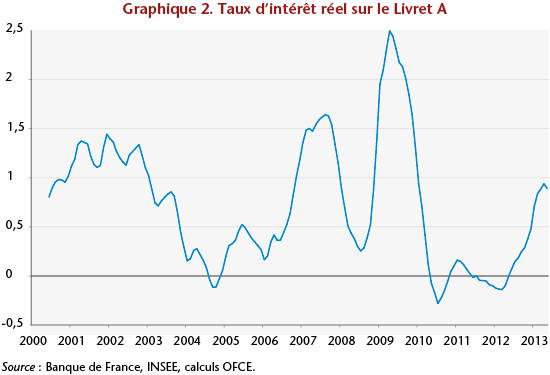

Even though the authors’ observations seem fair – social housing does not play its full role, and the systems of construction and allocation are complex and inefficient – the solutions that they propose are less so, and are not very consistent. The debate on the role and place of social housing in France is old. Should it be reserved for poor households, thus abandoning the goal of social diversity? If this is done, should the eligibility ceilings be reduced, even though today more than 60% of the population might be entitled to social housing? Should social housing be profitable? Is there a sufficient supply of it? The idea put forward by the authors, according to which the State, through subsidized loans to housing agencies (HLMs), is to take care of housing only the poorest households, and must leave housing for the working and middle classes to competition (promoters and private investors), is open to criticism, especially in these times of economic crisis. What is needed, on the contrary, is to increase the share of social housing as well as intermediate housing at “moderate” rents that is built with public funds to house the lower classes at reasonable rents and reduce tensions in critical areas. The authors’ idea that social housing is not a right to be granted ad vitam aeternam seems justified. In 2006, according to the INSEE, more than one out of ten tenants in social housing belonged to the fifth quintile (the richest 20%). Unless one believes that social housing should, in accordance with the principle of social diversity, be open to all, then it is necessary to strengthen measures to encourage these households to leave social housing and direct them to the private sector, or accession needs to be tightened, as the additional rental charges currently applied are not effective enough. But the age of the occupants has to be taken into account, along with the availability of nearby housing at market rents. For housing the lower and middle classes (that is to say, “profitable” operations), the authors also suggest developing competition between private agents (developers, private builders, etc.). Once the amortization period of the loan from the Caisse des Depots et Consignations (CDC) expires, the housing thus built could change status and either switch into the private sector or be sold. This idea gives the impression that the shortage of social housing is the consequence of a lack of available funds. However, thanks to the amounts deposited in Livret A savings accounts, there is no lack of money. The brakes on housing construction are to be found elsewhere (lack of political will, lack of land, etc.). Even tType text or a website address or translate a document. hough it is necessary to fight against urban segregation and the way to do this is by “disseminating poor households throughout the urban fabric”, the proposals of the authors of the CAE note are not realistic. The index of spatial segregation proposed (see Box 10 in the working paper) would lead to no longer building social housing in areas where it is already significantly concentrated. However, given the land constraints in high-pressure areas, this is not feasible. The objective of the fight against segregation should not take priority over the goal of construction but complement it. Public funding that is rigidly conditioned on the value of one or two indicators, even the most transparent ones, as proposed by the authors, would be extremely complex to implement. The SRU law establishing identical goals for communes with very different characteristics needs to be amended. Social housing needs to be built in accordance with need and demand. Currently, however, there is no match between supply and demand even in the less problematic areas (housing too big or too small, too old, etc.). According to the INSEE, 14% of social housing tenants are thus in a situation of over-occupation (twice the proportion seen in the private sector). Not only is entry into social housing difficult, but so is mobility within the sector. It is thus necessary to build social housing massively not only to accommodate new populations but also to house current social housing tenants in better conditions. Should the housing issue be de-municipalized? It is certainly a mistake to leave urban decision-making (and action) up to the municipalities alone, as some may be encouraged to give preference to selling off the available land to private developers rather than to housing agencies, whether this is directly for financial reasons or in an effort to attract a relatively affluent population without social problems. Housing policy thus requires strong incentives for the construction of social housing, including aid specifically for the municipalities where it is located, along with legal constraints and compensatory taxation targeted specifically at towns that have no social housing. The SRU Law is necessary. Note that proposals along these lines are difficult to get adopted at the political level. Thus, the measure to provide for inter-communal decision-making power regarding in particular the Local Urbanism Plan (PLU), a provision in the ALUR law, was largely rejected by the Senate, with the support of the Minister of Housing [6]. Similarly, the Union sociale pour l’habitat (social housing union), while deploring the lack of social mobility in the sector, regularly opposes any significant changes to the allocation process that could lead to greater mobility, with each organization striving to protect its own criteria.

Rent and housing aid between taxation and imputation

In the CAE note, the way the tax system takes account of housing costs is the subject of questionable proposals. We agree of course with the starting point: it would be desirable to achieve a certain tax neutrality between income from financial capital and implicit rents. This is necessary from the point of view of both economic efficiency (not to overly encourage investment in housing) and social justice (given equal taxable income, a landlord and tenant do not have the same standard of living). But we believe this can be done effectively only by taxing implicit rents. It is difficult to undertake such a reform today, when substantial tax increases have already occurred. It would be difficult to introduce a new tax. This would therefore have to be accompanied by an upward translation of the tax brackets, so that, if owners pay more, tenants pay less. This could, furthermore, divert some households from building housing; the proceeds would be used in part for the construction of housing, which is inconsistent with the previous proposal to use these to reduce tenants’ taxes. This would thus have to be introduced only very gradually. First the property tax bases would be re-valued. Then this database (from which landlords accessing it could deduct borrowing costs) could be used to tax the rental values at the CSG (wealth tax) or IR (income tax) rates (with some deduction). Fearing that this measure would be unpopular, the authors suggest that tenants could deduct their rent from their taxable income (with a relatively high ceiling of around 1000 euros per month). This proposal is not acceptable: – it is arbitrary: why not also deduct, still with ceilings, spending on food (no-one can live without eating) or on clothing, transportation or mobile phones (now indispensable). This could go on forever. The IR tax scales already take into account the need for a minimum income level (for a couple with two children, taxation only kicks in above a wage income of 2200 euros per month). The authors’ measure would privilege housing costs over other spending, with little justification; – the tax savings achieved in this way would be zero for non-taxable persons, and low for those near the taxation threshold: a family with two children and an income of 3000 euros per month with 600 euros in rent would pay 700 euros less tax; a wealthy family taxed at the marginal rate of 45% could save 5400 euros in tax, or 450 euros per month, that is to say, more than the housing benefit of most poor families; – the measure would be very costly. The authors do not give us a precise estimate, but lowering the taxable income of 40% of the 18 million taxable households in France (the proportion of tenants) by 10,000 euros could reduce IR tax revenue by 14 billion. In fact, this must necessarily be offset by a downward translation of the tax brackets. At the end, here, too, if the tenants pay less, the landlords pay more. Furthermore, the measure would be less effective economically than the taxation of implicit rents, since it would introduce a bias in favour of housing costs and does not take into account the value of the property occupied. The authors propose integrating the housing allowance into the IR tax and having all this managed by the tax administration, which would be responsible for developing a coherent redistributive policy on behalf of people on low incomes. While the current system of housing assistance can of course be improved, once again the authors’ analysis is one-sided, and does not include all the aid given to the poorest (the “RSA socle” – basic income supplement for the unemployed; the “RSA activité” – income supplement for the working poor; and the “PPE” – in-work negative income tax). They forget that helping low-income people requires personalized support, in real time, on a monthly or quarterly basis, which the tax administration is unable to provide. In fact, they wind up with a system that is hardly simplified: the tax authorities would determine housing assistance for non-taxed households that the CAF Family Allowance fund would pay monthly and which would be adjusted by the tax administration the following year. But it is left unsaid whether the same formula would apply to the RSA income supplement. For taxable persons, the assistance would be managed by the tax authorities. The authors tell us that, “the aid could not be less than the current housing allowance”, but their proposal would greatly increase the number of untaxed households for whom it would be necessary to compare the tax savings and the allowance using the old formula. This is not manageable. It would of course be desirable to simplify the calculation of the housing allowance and to better integrate it with the RSA income supplement. This should be included in a reform of the RSA that the government needs to undertake (see the Sirugue report and the criticism of it by Guillaume Allègre), but the overall arrangement must continue to be managed by those who know how to do this, the CAF family fund, and not the tax authorities.

Readers interested in housing-related issues should see the Revue de l’OFCE “Ville & Logement”, no. 128, 2013.

[1] Trannoy A. and E. Wasmer, « La politique du logement locatif », Note du CAE, n°10, October 2013 and the document de travail associé [both in French].

[2] Note that the German market is very different from the French market (majority of renters, little demographic pressure, etc.), and that its rules cannot therefore be transposed.

[3] Currently, in the Paris region and more generally in all the so-called high-pressure neighbourhoods, the difference in rent between those who moved during the year and tenants who have been in their homes over 10 years exceeds 30% (38% for Paris) (OLAP, 2013).

[4] Indeed, “old” investors potentially have higher rates of return than do “new” investors.

[5] As the number of new households is tending to fall (Jacquot, 2012, “La demande potentielle de logements à l’horizon 2030”, Observation et statistiques, N°135, Commissariat au Développement Durable).

[6] An amendment according a low level for a blocking minority to France’s “communes” during changes to the PLU (25% of communes and 10% of the population) was adopted by the Senate on Friday, 25 October – an amendment thereby reducing in practice inter-communal authority in this area.