At a time when the outlook for world trade outlook remains glum [1], British domestic demand is struggling to remain dynamic: household consumption has run out of steam at the end of the year, while investment fell by 1.4 points in 2018.

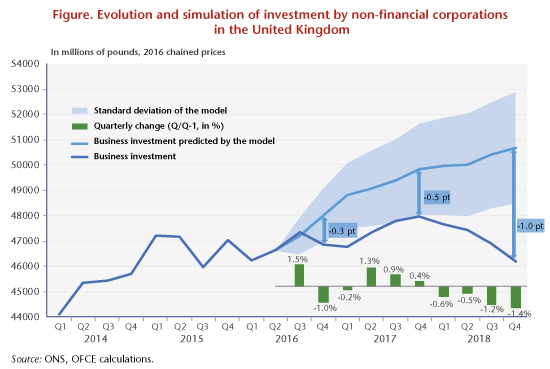

This latest fall can be attributed almost entirely to the investment of non-financial corporations [2] (55% of GFCF in volume), which fell consecutively during the four quarters of the year (Figure 1), for a total fall of -3.7% in 2018.

Investment can be predicted by an error-correction model [3], and the one used for the investment forecasts of non-financial firms in the United Kingdom benefits from an adjustment that can be considered “correct” in terms of its explanatory power (86%) over the pre-referendum period (1987Q2 – 2016Q2). If we simulate the trajectory of investment following the 2016 referendum (in light blue), we can see that it deviates systematically from the investment data reported by the ONS (dark blue) [4].

This result is consistent with the results found in the recent literature, which also show that the models have consistently tended to overestimate the investment rate of UK firms since 2016 [5]. The gap has steadily risen in 2018, from 0.5 percentage point of GDP in 2017, to almost one point of GDP in the last quarter.

What explains the gap? We interpret this deviation as the effect of the uncertainty arising from Brexit, particularly that on the future trade arrangements between the UK and the EU. Nearly half of Britain’s foreign trade comes from or goes to the single market. Although the inclusion of an uncertainty indicator (Economic Policy Uncertainty – EPU, see Bloom et al., 2007) in the investment equation failed to identify it clearly, several studies on data from UK firms point in this direction. First, periods of heightened uncertainty moved in line with significantly lower investment after the 2008 crisis (Smietbanka, Bloom and Mizen, 2018). In a scenario without a referendum (no Brexit), the transition to a regime with renegotiated customs tariffs would have had the effect of:

– Reducing the number of companies entering the European market and increasing the number exiting (Crowley, Exton and Han, 2019);

– Weighing on business investment with the prospect of tariffs similar to those prevailing under WTO rules (Gornicka, 2018).

The reduction in investment “cost” 0.3 percentage points of GDP in 2018, and this cost could rise as second-round effects are taken into account (which is not the case here). If the uncertainties do not rise, the “Brexeternity” – an expression used to characterize the relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union, that is to say, inextricable – could have a much more depressing effect on Britain’s future growth and its citizens’ standard of living.

[1] The WTO composite indicator has stayed below (96.3) its long-term trend (100) since mid-2018.

[2] Reported by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) as Business Investment. Non-financial corporations partially or wholly owned by the government are included in this field, but they account for less than 4% of the total. This measure of investment does not include spending on housing, land, existing buildings or the costs related to the transfer of ownership of non-produced assets.

[3] See the article by Ducoudré, Plane and Villemot (2015) in the Revue de l’OFCE, for more information on the strategy adopted.

[4] A slight gap can be seen from 2015, when the law on the referendum was adopted.

[5] In particular the work of Gornicka (2018).

Leave a Reply