Should we be celebrating the fall in unemployment at end 2013?

By Bruno Ducoudré and Eric Heyer

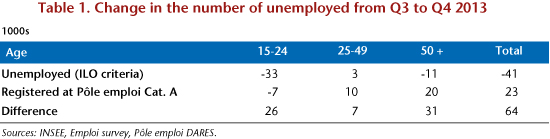

Every quarter, the INSEE publishes the unemployment rate as defined by the International Labour Office (ILO): for the fourth quarter of 2013, it fell 0.1 point in France, meaning 41,000 fewer unemployed. Likewise, every month the number of jobseekers registered with the Pôle Emploi job centre is reported: during the fourth quarter of 2013, this source indicated that the number of registered jobseekers in category A rose by 23,000. In one case unemployment is down, in the other it is up – this does not lead to a clear diagnosis about where unemployment is heading at year end.

What explains the difference in diagnosis between the INSEE and Pôle emploi?

Besides differences related to methodology (an employment survey for the ILO, an administrative source for Pôle emploi), it should not be forgotten that, according to the ILO, a person must meet three conditions to be counted as unemployed: being unemployed, being available for work and performing an active job search. Simply being registered at Pôle emploi is not sufficient to fulfil this last condition. So people registered as category A at Pôle emploi who are not actively seeking work are not counted as unemployed according to the ILO. The ILO criteria are thus more restrictive. Historically, for those aged 25 and over, the number of unemployed registered at Pôle emploi is greater than the number according to the ILO criteria. For those under age 25, registering with Pôle emploi [1] is in general not as worthwhile, except during a period of active social treatment of unemployment, as was the case during the last quarter of 2013: people who wanted to benefit from a subsidized job had to be registered at the job centre.

As shown in Table 1, regardless of the age group, the situation seems less favourable using the Pôle emploi figures than according to the ILO criteria: when confronted with more than 2 years of unemployment, a certain number of discouraged jobseekers stop their active job search and are thus no longer recognized as such within the meaning of the ILO, yet continue to update their status at the job centre, and therefore remain listed in Category A.

Is the reduction in the unemployment rate calculated by ILO criteria good news?

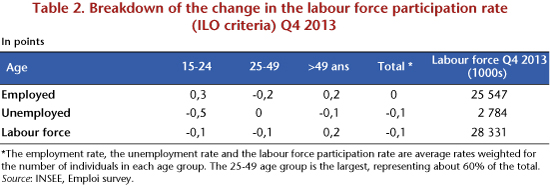

The unemployment rate can fall for two reasons: the first one, virtuous in nature, is as a result of escaping unemployment due to improvements in the labour market; the second, less encouraging, is due to jobless people becoming discouraged and drifting into inactivity. The latest statistics from the ILO emphasize that the 0.1 point fall in the unemployment rate can be explained in full by the fall in the participation rate – which measures the percentage of the work force in the population aged 15 to 64 – and not by a resumption of employment that has remained stable. The decline in the unemployment rate is thus not due to a recovery in employment, but to discouraged jobless people who quit actively seeking employment (Table 2).

Looking more closely, the employment policy pursued by the government – “jobs for the future”, CUI “unique integration contracts” – has had a positive impact on youth employment; the employment rate rose by 0.3 percentage point during the last quarter of 2013. Among seniors, the employment rate is still continuing to rise (+0.2 percentage point) due to the decline in the actual age of retirement. ILO-defined unemployment is of course falling among seniors, but the sharp rise in enrolment at the job centre in this age group (Table 1) undoubtedly reflects a change in their job search behaviour: more and more seniors are no longer looking for work. They are now included in the “halo” of unemployment, which is continuing to rise.

Ultimately, the fall in the ILO-defined unemployment rate, which is characterized by the absence of a recovery in employment and the discouragement of jobseekers, is not such good news.

[1] To have the right to unemployment compensation and receive assistance for a return to work, it is necessary to prove a 122 day contribution period or 610 hours of work during the 28 months preceding the end of the job contract.