The dilemma of competitiveness

The competitiveness of a country is a complex subject. Some people rebel against the very concept on the grounds that it can’t be applied to a nation and is only meaningful for companies. It is true that if a company gains market share, this necessarily comes at the expense of a competitor. And it is no less true that when one country increases its exports to another, then the extra income earned by the first will, in part, fuel demand that then benefits the second. The benefits of one become a condition of benefits for the other. This back-and-forth justifies international trade, whose aim is a better use of resources by everyone, with the benefits being shared by all, on an equitable basis. This story makes sense. And it does indeed indicate that the competitiveness of a nation is not comparable to that of a business.

However, there are global imbalances that result in longer-term surpluses or deficits that reflect differences in the competitiveness of the companies in the countries in question. These require appropriate policy responses to meet the challenge of making possible what some have called the return journey, that is to say, to set in motion the mechanisms through which the income earned by one country is converted into demand on the other.

This is the difficulty facing France today. The country has been building up trade deficits since 2002: it is facing a problem with the competitiveness of its companies on global markets, and is no longer able to use the exchange rate instrument. The persistent trade deficit is clearly of even greater concern than the public deficit, and its absorption should be a priority. This is why calls have been mounting for a competitiveness shock, that is to say, economic policy measures that are able to make companies more competitive by reducing their production costs.

That said, a competitiveness shock is not easy to implement. Of course, in a developed economy, business competitiveness primarily means non-cost competitiveness that is based on a company’s ability to occupy a technological or market niche. But regaining this type of competitiveness requires investment and time. Furthermore, non-cost competitiveness is not independent of immediate price competitiveness. Quickly rebuilding business margins is a necessary, though probably not sufficient condition for a return to non-cost competitiveness. This requirement is all the more stringent today as obtaining captive markets through differentiation can often be very costly in terms of R&D and exploring customer prospects.

The difficulty facing the French economy is that the restoration of margins needed may come at the expense of household purchasing power and thus of domestic demand. Competitiveness gains could remain a dead letter if final demand were to collapse. Moreover, there is nothing to say that restoring margins per se will result in a pick-up in investment if companies face just such a slowdown in demand, if not a fall.

It seems that what is needed is to grasp both ends of the chain: short-term price competitiveness and medium-term non-price competitiveness. Quickly restoring business margins requires transferring the financing of social protection to taxes on households. Enabling companies to re-establish their price competitiveness demands further improvements in the level of infrastructure and support for the establishment of productive ecosystems that combine good local relationships and the internationalization of production processes. In both cases, this involves the question of what fiscal and budget strategy should be implemented.

The difficulty comes from the prioritization of objectives. If priority is given to immediately restoring the public accounts, then adding another burden due to the transfer of charges onto the tax grabs already taken from households will definitely run the risk of a collapse in demand. This means either admitting that such a transfer is really possible only in conditions of relatively strong growth and thus postponing it, or making the improvement of the trade deficit a priority over the public accounts and thus not tying our hands with a budget target that is too tough.

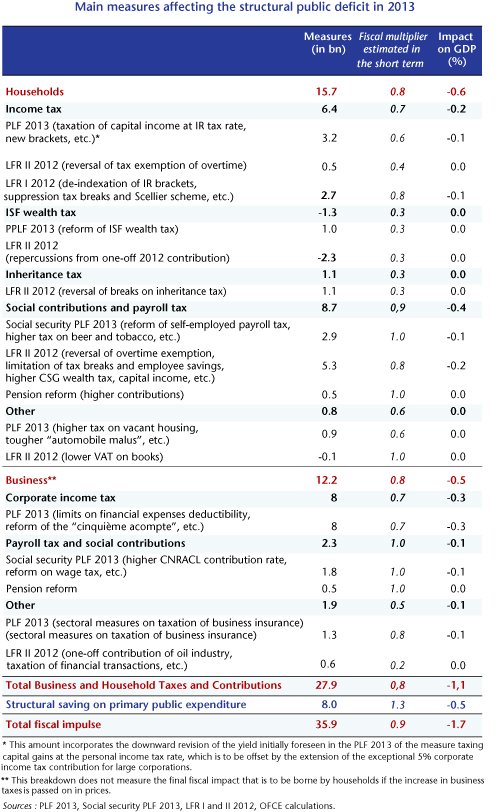

The government has decided to stay the course of public deficit reduction, and has in fact postponed the competitiveness shock by proposing, after a year or more, business tax credits that are to be offset by hikes in the VAT rate in particular. The underlying rationale is clear. The search for a balanced budget is supposed to guarantee a return to growth, but care is being taken about further weighing down demand by adding to the tax increases already enacted to meet the target of a 3% government deficit by 2013. The prevailing idea is that, aided by a wise budget, a pick-up in activity will take place within two years in line with the supposedly conventional economic cycle, which has the additional advantage of coinciding with the electoral cycle.

The path being chosen is narrow and, quite frankly, dangerous. Fiscal austerity measures are still subjecting domestic demand to heavy pressure. The restoration of business margins has been put off. Would it not be better to stagger the recovery of the public accounts more and ensure more immediate gains in competitiveness by using the appropriate fiscal tools?

The result to be expected from either of these strategies is of course highly dependent on the choices being made at the European level. Persevering on the path of widespread austerity will mean nothing good will happen for anyone.