By Sarah Guillou

Following a meeting of the Ministers of Industry in Brussels on 20 February 2014, Arnaud Montebourg criticized the European Commission’s control of aid, which he considers too strict at a time when industry needs assistance. He wants aid for energy-intensive industries to receive an exemption due to competition from US companies that have much lower energy costs (estimated, on average, at one-third of the cost in Europe). More generally, Arnaud Montebourg was very critical of Joaquin Almunia, the European Commissioner for Competition. So is the Minister of Industrial Renewal (Redressement productif) right to castigate the control of State aid by the European Commission?

What does public aid for business entail?

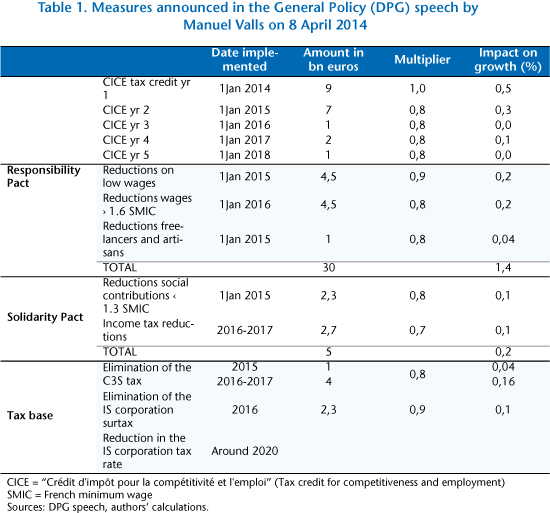

“A transfer of wealth, directly or indirectly, from a public entity to an autonomous economic entity” – public aid to business can take a variety of forms. In France, half of State aid is made up of tax expenditures (tax credits or various exemptions), a third of financial support (loans, guarantees, capital), and the rest consists of direct and indirect subsidies.

A recent report by the General Inspectorate of Finance (IGF 2013) estimated the amount of public aid granted by the central government and local authorities to economic actors at 110 billion euros. Included in this total are measures such as reduced VAT rates (18 billion), reductions on social security contributions on low wages (21 billion), the CIR research tax credit (3.5 billion), as well as more than 600 State schemes and even more under local authorities.

The report highlights the complexity of the system of aid, which is the result of a kind of sedimentation of successive measures, sometimes with intervention levels intermingled, and with many programmes involving small amounts. Criticizing the goals and effectiveness of this system, the report’s authors lament that industry is not a bigger target: ultimately it receives only 2 billion euros (excluding CIR and relief from social security contributions and VAT), while agriculture receives 4 billion.

What justifies the European Commission’s control of public aid?

A direct consequence of the implementation of the single market, Europe’s control over State aid is a tool of European competition policy that is intended to ensure the existence of fair competition and to fight against distortions created by advantages granted by a State to its own companies. The fight against a “race to the top” in terms of aid is thus subject to control. Under Article 87, paragraph 1, of the Treaty establishing the European Community, State aid is deemed incompatible with the common market, and Article 88 gives a mandate to the Commission to control such aid. But Article 87 also specifies the criteria that make aid “controllable” by the Commission.

A policy of support comes under the control of the Commission if it involves 1) specific aid (aid not paid to all firms or households, such as a general tax reduction), 2) the support policy involves a commitment of the State’s public finances, whether direct grants, soft loans, tax credits, the supply of equipment, etc. 3) the support provides a specific advantage to companies, an industry, or a region (which they would not have received without the State’s intervention) 4) the support distorts competition and may affect trade between the Member States – the de minimis rule exempts small amounts of aid.

What aid requires notice to the European Commission?

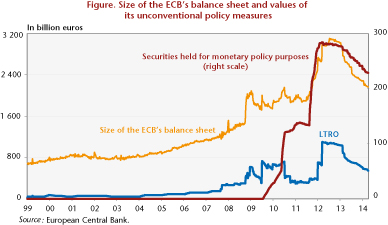

Aid to companies is subject to approval by the European Commission when it exceeds 200,000 euros over three years and it is not covered by arrangements for exemptions decided by Europe. In theory, aid may be granted only once the Commission’s approval has been obtained. This is binding at a time of emergency measures and undeniably affects economic sovereignty. The interval between notification and a decision can range from 2 months to 20 months, or even more if an investigation is needed. The Commission has the power to require the reimbursement of aid that has been already paid and is deemed illegal; the EU Directorate-General for Competition exercises this control, with the exception of aid for agriculture and fisheries, which is under the control of their respective directorates. Legislation is constantly being adjusted to the economic situation, as happened at the time of the financial crisis in order to support the banking sector.

In an effort to simplify the controls and reduce administrative burdens, a general regulation on block exemptions, adopted in 2008, has clarified cases where no notification is necessary. There are numerous exemptions, which revolve around the following five themes: the Lisbon strategy, sustainable development, the competitiveness of EU industry, job creation, and social and regional cohesion. This system of exemptions shows that control is also an expression of European policy choices that are guiding State aid, and therefore public resources, towards uses that accord with these choices.

Is aid often refused?

According to Mr. Almunia, 95% of the aid examined is authorized. The statistics provided by the 2000-2013 Scoreboard (DC, Europa Scoreboard) show that 88% of notifications related to industry and services lead to the conclusion that the support measure in question does not fall within the definition of public support, hence there is no objection. Another 5% of decisions are positive, and 1% are conditional. This comes close to the 95% cited. The remaining 5% consist of support measures that have been rejected by the Directorate for Competition, part of which (4%) will be recovered. Since 2000, this amounts for all the Member States to 251 refusals, the equivalent of an annual average of 22 refusals from 2000 to 2007, and 12 from 2008 to 2013.

The notifications from the French State overwhelmingly concern regional aid, especially for the DOM-TOM overseas territories, aid for certain agricultural sectors, and aid for R&D. For example, aid to Renault’s HYDIVU project from the Agency for the environment and energy, notified in March 2013, resulted in a decision in October 2013 that the measure did not raise any objections. The aid to R&D for innovative young companies notified in December 2013 led to a decision in February 2014 by the Directorate for Competition that the measure did not raise any objections and was covered by the exemptions for support for R&D.

More recently, the Commission agreed to the State’s entry into PSA’s capital after having accepted the need for the company’s restructuring in July 2013 (decision SA.35611). This capital acquisition was not found to constitute State aid. The French State was considered a private investor, just like the Chinese company Donfeng.

In 2013, the French government issued 47 notifications, none of which raised objections. To date only one is under investigation: the alleged subsidies to public transport in the Ile-de-France region around Paris.

What is France’s position with regard to State aid?

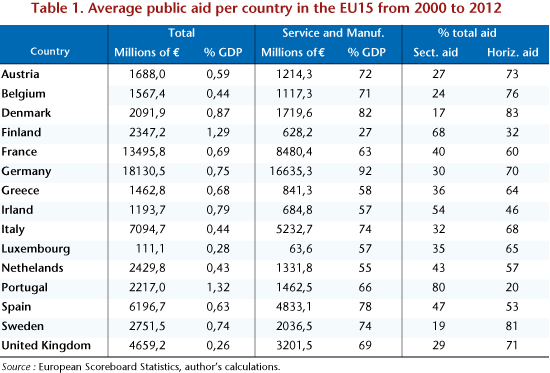

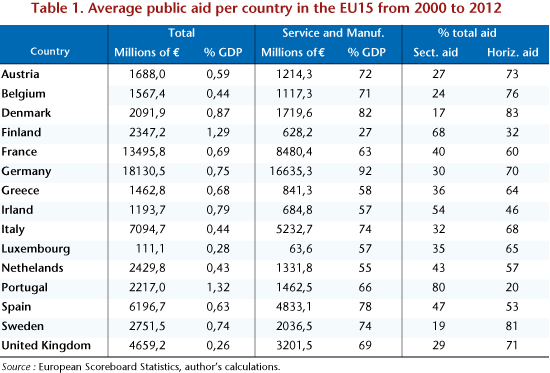

Of all the notifications addressed by Member States to the Directorate for Competition from 2000 to 2013 – i.e. 4765 in the field of industry and services – France sent 8.8%, compared with 10% for Italy and Spain, 17% for Germany and 6.4% for the UK. The French State, so often accused of a Colbertist tendency, on average gave notice over the period of about half as much aid as Germany. The statistics provided by the “Scoreboard on State aid” (DC, Aid in volume and as a % of GDP) can be used to see France’s position in the EU15 in terms of the volume of aid granted relative to GDP. Table 1 shows that France is about average: higher than the group of countries with a free market tradition (UK, Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Luxembourg) but below countries with a social-democratic tradition (Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Germany). With regard to the volume of aid relative to its purpose, it is customary to distinguish sectoral aid that benefits a particular sector, an “old version” brand of industrial policy, from horizontal aid that caters to all businesses, a “modern” brand of industrial policy, such as support for R&D. Once again, France occupies a middle position in terms of the percentage of sectoral aid relative to the EU15 group.

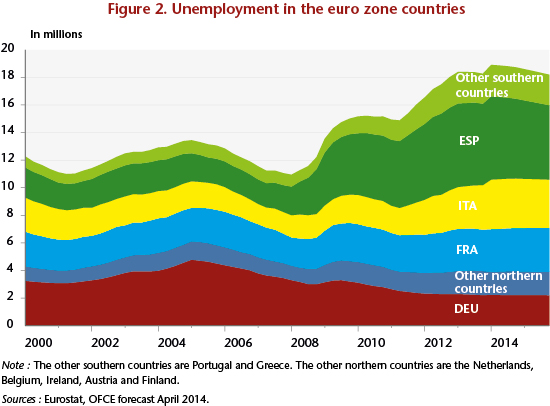

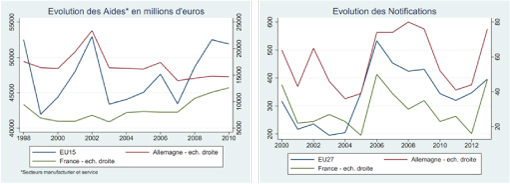

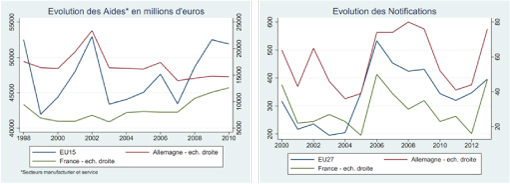

Both the volume of aid and the notifications are very sensitive to a country’s economic and institutional environment and to shocks to this environment (German reunification, industrial restructuring, etc.). France is among the countries that have granted more aid in the recent period (2010-2012) than in the beginning of the crisis period (2007-2009). Countries that are comparable to it (Germany, Italy, Spain) have instead reduced their aid payments. The following graphs show changes in the volume of aid (constant euros). While the amount of aid clearly increased in 2007, the crisis does not seem to have fundamentally altered behaviour in terms of notifications. Aid for the banking industry is the subject of a specific legal system and separate accounting. The amounts described therefore do not include aid to the banking sector.

Source: DC, Europa State Aid Scoreboard Statistics.

There is nothing to show that the European Commission’s controls on aid have hurt industry

This brings us to the question that concerns our Minister. If the level of public aid is positively correlated with manufacturing’s share in the economy (see Guillou S., 2014), this is mainly because the characteristics of the manufacturing industry – regional imbalances, R&D, environmental investment – correspond more to the criteria for the authorized payment of aid. The manufacturing sector has also been characterized historically by lobbying, a potential trigger for aid, and is also the sector most exposed to international competition. There is no evidence that the causality would run from State aid to manufacturing’s share of value added. The reverse is much more likely.

Moreover, a careful analysis of the European Commission’s control of aid shows that negative decisions are relatively rare. But a strong inhibitory effect cannot be excluded, in the sense that governments might exercise self-censorship in light of their knowledge of the case record of Europe’s Directorate for Competition. This kind of censorship is difficult to quantify, but it is detectable for all the Member States in the decrease in notifications since controls were implemented.

There is however much room for exemptions, spaces in which aid to industry may be authorized. If indeed it is not possible to envisage a “CICE” tax credit that would be reserved for companies in the manufacturing industry alone, as this would be too selective, any measure is acceptable that is considered support for innovation and R&D, the development of renewable energies, the handling of regional and major sectoral imbalances, or job creation.

Moreover, a judgment on aid’s legality is based on an economic cost-benefit analysis, which is sometimes not exempt from criticism or debate, but is undeniably based on an economic assessment of the allocation of public funds and of any distortions in competition that this allocation could create. There are a priori rules mandating rejection or acceptance, but most cases are subject to a reasoned economic analysis. This consists of a “balancing” between “the contribution to the attainment of an objective of well-defined common interest”, such as efficiency or equity, and “the resulting distortion of competition and trade”. The measure is also reviewed in order to determine its appropriateness, its effectiveness as an incentive and its proportionality. Finally a comparative scenario, a sort of counterfactual that envisages no implementation of the aid, is also used to help reach a decision.

On the question of support for energy-intensive industries, firms that consume electricity intensively have generally negotiated preferential rates with energy providers. This was the case in France with the Exeltium consortium, but it is also the case in Germany. Whether this involves preferential tariffs granted by a State-owned company (historical supplier) or a tax exemption or reduction, these measures have been analyzed by the Directorate for Competition. To date, these special rates have not encountered systematic opposition, but the process of deregulating Europe’s electricity market and the new regulation on aid for the environment and energy – scheduled for the first half of 2014 – should not necessarily work in their favour. It is still the case that the best support for industries that intensively consume energy, and not just electricity, remains the appreciation of the euro vis-à-vis the dollar, which is reducing the cost of imported energy, even though this is rather debilitating for exporters, as our Minister frequently points out. In addition, the cost of energy is an incentive (among others) to invest in energy-saving technologies. This perfectly illustrates the economic adage that any choice (aid) is also a renunciation (of another use of resources). The competitiveness of energy-intensive industries or a policy to reduce fossil fuels – this is the choice at the heart of the European Commission’s decisions.

Control on aid is aimed at a different type of objective

It is because the control of State aid is consistent with European objectives (Lisbon Objectives, 2008 Climate and Energy Package, and now the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework) that it might be possible to develop a coherent European economic policy.

The regulatory system and the jurisprudence on public aid have proven to be relatively flexible and adaptive. This should not prevent us from discussing and commenting on the decisions of the Directorate General for Competition, particular as competition policy does not need to resemble a doctrine to be effective. It does, of course, entail some loss of economic sovereignty. But it needs to be recognized that control over aid is a major element in European economic cohesion, in the convergence of economic levels, and most of all in democracy. This reporting requirement generates valuable information for citizens about the use of public funds. Furthermore, it facilitates the readability of industrial policy and more generally of public aid from States, which citizens and the media have an interest in assessing on the eve of the upcoming European elections.