Should we be worried about the slowdown in China?

By Eric Heyer

China’s growth is slowing. This does not really come as a surprise: the slowdown was announced by the Chinese authorities; it can be seen in the national accounts; and it was predicted in all the medium-term scenarios of the major international organizations. It corresponds to a new phase in China’s economic and social development, towards growth that the authorities want to be more “qualitative, inclusive and innovative”.

However, many analysts and experts believe that the Chinese economy has slowed down more than is reflected in the country’s national accounts. According to a survey conducted in 2015 by Bank of America Merrill Lynch, 75% of investors are convinced that the real growth rate of the Chinese economy was less than 6% in the second quarter of 2015 on an annualized basis. For some, the overestimation of growth is due to an underestimation of inflation, particularly in the service sector. For others, China’s GDP growth rate needs to be correlated with the rate for electricity generation and be in line with freight by road, rail, sea or air. However, all these values have experienced a significant decline since the start of 2014, and the stable relationship between GDP and these elements tends to indicate lower annual growth for the Chinese economy, of around 2% in early 2015 according to Artus, which is more in line with the observed fall in imports. This steeper slowdown would have a violent impact on the global economy, endangering the shoots of recovery in the developed economies.

In a recent article, we estimated the link between Chinese GDP and different economic variables not taken from the national accounts, using an error correction model (ECM) to evaluate the slowdown, before giving an evaluation of its impact on the GDP of the major developed countries.

Just how much is the Chinese economy slowing down?

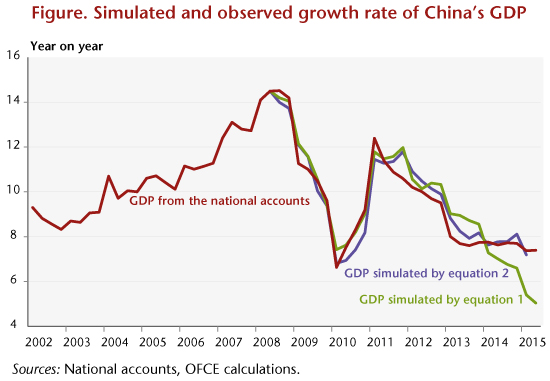

Drawing on the Li Keqiang index, we estimated China’s GDP from variables for freight and the production of electricity and cement. While our results confirm that the Chinese economy has been slowing down since 2011, from a yoy rate of 12% to less than 8% in early 2013, the stabilization of the growth rate observed since then in the national accounts is not re-traced in this simulation, which indicates instead a continued slowdown in Chinese growth (Figure 1, equation 1).

However, this modelling of GDP does not take into account the major transformation of the Chinese economic model towards a new growth model, which began three years ago and which involves high indebtedness of domestic agents and an orientation towards more services. An enhanced analysis of variables that also draw on the labour market situation (wages, jobs) confirms the slowdown in the Chinese economy as traced by the national accounts, reflecting the difficulty of the transition between the two growth models, and not the beginnings of a slide into recession (Figure 1, equation 2). On the other hand, the country’s “industrial” part should continue to decelerate, thwarting any significant rebound in Chinese imports.

What impact will the slowdown have on the developed countries?

Three channels for the transmission of the slowdown of the Chinese economy to the developed countries can be identified:

- Direct and indirect effects via the trade channel: Given China’s weight in world trade, the sharp slowdown in its output, particularly in industry, is significantly reducing the country’s imports (through intermediate consumption and household consumption) and is consequently cutting demand for the rest of the world’s goods. To this direct effect can be added an indirect effect due to the slowdown in partner countries affected by the reduced demand;

- Effects via the financial channel: The Chinese slowdown may hit direct investment in the developed countries; conversely, the withdrawal of capital from China might be an occasion for reallocating it to other developed countries;

- Effects via the channel of raw materials prices: As China buys more than half of all metals traded in the world and accounts for two-thirds of the increase in global oil consumption, the slowdown of its economy is hurting the prices of raw materials, especially oil, thereby causing a transfer of income from the countries producing commodities to the countries consuming them.

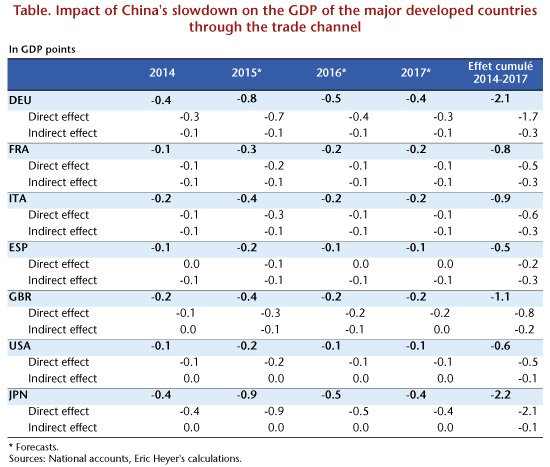

Looking only at the first transmission channel, trade, our results are as follows: Japan and Germany are the countries most affected by the slowdown in China. The cumulative impact from 2014 to 2017 will amount to more than 2 percentage points of GDP. The impact on Japan is due to its significant exposure to Chinese trade (3% of exports to China compared with 2.4% for Germany), whereas the impact on the German economy is due more to its degree of openness (39.1% against 14.6% for Japan). Next come the United Kingdom, Italy and France, with a cumulative impact of close to 1 GDP point. Spain and the United States are least affected, with a cumulative impact of around 0.5 GDP point: the United States has a low exposure (0.7%) and a low degree of openness (8.2%). Finally, the annual peak for the impact of China’s slowdown would hit in 2015, and knock 0.8 GDP point off the German economy and 0.9 GDP point off the Japanese economy.