Does the fall in the stock market risk amplifying the crisis?

By Christophe Blot and Paul Hubert

The Covid-19 crisis

will inevitably plunge the global economy into recession in 2020. The first

available indicators – an increase in the unemployment rolls and in partial

unemployment – already reveal an unprecedented collapse

in activity. In France, the OFCE’s assessment

suggests a 32% cut in GDP during the lockdown. This fall is due mainly to stopping

non-essential activities and to lower consumption. The shock could, however, be

amplified by other factors (including rises in some sovereign rates, falling oil

prices, and capital and foreign exchange movements) and in particular by the

financial panic that has spread to the world’s stock exchanges since the end of

February.

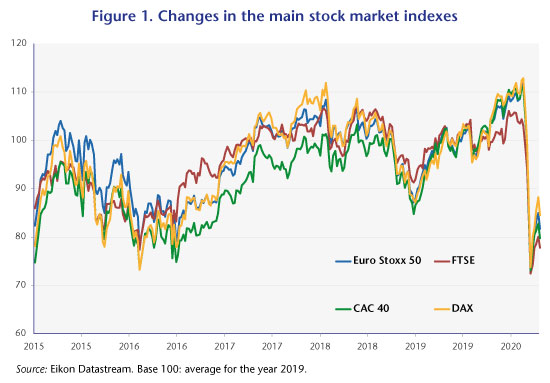

Since 24 February

2020, the first precipitous one-day fall, the main stock indexes have begun a

decline that accentuated markedly in the weeks of March 9 and 16, despite

announcements from the Federal Reserve

and then the European Central Bank (Figure 1). As of 25 April, France’s CAC-40 index had

fallen by 28% (with a low of -38% in mid-March), -25% for the German index and nearly

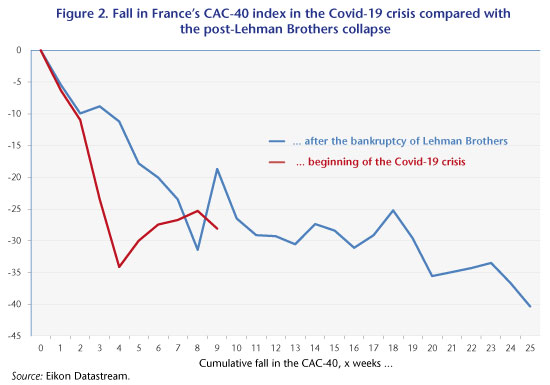

-27% for the European Eurostoxx index. This stock market crash could revive

fears of a new financial crisis, only a few years after the subprime crisis. The

fall in the CAC-40 in the first few weeks was in fact steeper than that

observed in the months following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September

2008 (Figure 2).

While the short-term impact

of the Covid-19 crisis could prove to be more severe than that of the 2008

financial crisis, the origin of the crisis is very different – hence the need

to reconsider the impact of the stock market panic. In the financial crisis,

the origin was in fact a banking crisis, fuelled by a specific segment of the

US real estate market, the subprime market. This financial crisis then caused a

drop-off in demand and a recession through a variety of channels: higher risk

premiums, credit rationing, financial and real estate wealth effects,

uncertainty, and so on. While some of these elements can be found today, they

are now being interpreted as the consequence of a health crisis. But if there

is no doubt that this is at the outset a health and economic crisis, can it

trigger a stock market crash?

Another way of posing

the question is to ask ourselves whether the current stock market fall is due entirely

to the economic crisis. Share prices are in fact supposed to reflect future changes

in a company’s profits. Therefore, expectations of a recession, as demand –

consumption and investment – and supply are constrained, must result in a reduction

in turnover and future profits, and therefore a fall in share prices.

However, the financial

shock could be magnified if the fall in stock prices is greater than that

caused by the decline in corporate profits. This is a thorny issue, but it is

possible to make an assessment of a possible over-adjustment of the stock

market, and thus of a possible financial amplification of the crisis. The

method we have used is to compare changes in profit expectations (by financial

analysts) since the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis with the fall in equities.

Focusing on CAC-40 companies, profit expectations for next year have been cut in

the last three months by 13.4% [1]. This reduction should therefore be fully

reflected in the change in the index. In fact, the fall there was much larger:

-28%. This would result in an amplification of the financial shock by just

under 15 percentage points.

This over-adjustment by

the stock market can be explained by, among other things, the current

prevailing uncertainty about the way lockdowns around the world will be eased, and

thus about an economic recovery, as well as uncertainty about the oil shock that

is unfolding concomitantly, with determinants that are both economic and

geopolitical. This over-adjustment may therefore not be wholly irrational (with

regard to the supposed efficiency of financial markets), but the fact remains

that it has led to major variations in the financial assets of consumers and

business.

Variations like these

are not neutral for economic growth. On the consumer side, they contribute to

what are called the wealth effects on consumption: additions to a household’s assets

give it a sense of wealth that drives it to increase its consumption [2]. This effect is all the greater in countries where

household assets are in the main financialized. If a large portion of household

wealth is made up of equities, then changes in share prices strongly influence

this wealth effect. The portion of shares (or of investment funds) in financial

assets is quite similar in France and the United States, respectively 27% and

29%. However, these assets account for a much larger share of the disposable

income of American households: 156%, compared to 99.5% in France. As a result,

French households are less exposed to changes in share prices. Empirical studies

generally suggest a greater wealth effect in the United States than in France [3].

As for business,

these changes in stock market valuations have an effect on investment decisions

through collateral constraints. When a company takes on debt to finance an

investment project, the bank demands assets as collateral. These assets can be

either physical or financial. In the event of an increase in equity markets, a

company’s financial assets increase in value and allow it greater access to credit

[4]. This mechanism is potentially important today. At

a time when companies have very large cash requirements to cope with the brutal

shutdown of the economy, the sharp decline in their financial assets is restricting

their access to lines of credit. While the financial amplification factors are

not reducible to the financial shock, the recent changes in the prices of these

assets are nevertheless giving an initial indication of how the financial

system is responding to the ongoing health and economic crises.

[1] The data comes from Eikon Datastream, which for each

company provides analysts’ consensus on the earnings per share (EPS) for the

coming year and the following year. We then calculated the weighted average using

the weight of each CAC-40 company in the index of the change in these

expectations over the past three months. The fact that a 13.4% decline in

profit expectations for the next year will give rise to a 13.4% decline in the

stock price is made on the assumption that profits beyond the next year are not

taken into account, or, in other words, that their current net value is zero,

which is to say that investors’ preference for the present is very strong

today.

[2] More formally, we can speak of a propensity to

consume that increases as wealth increases. Wealth effects can be

distinguishable according to whether they are purely financial assets or also

include property assets.

[3] See Antonin, Plane and Sampognaro (2017) for a summary of these estimates.

[4] See Ehrmann and Fratzscher (2004) and Chaney, Sraer and Thesmar (2012) for empirical assessments of this transmission channel

via share prices or property prices, respectively.