Europe/US: How has fiscal policy supported income?

By Christophe Blot, Magali Dauvin and Raul Sampognaro

The sharp fall in activity and its brutal social consequences have led governments and central banks to enact ambitious support measures to cushion the shock, which resulted in an unprecedented global recession in the first half of 2020, as discussed in Policy Brief 78 . Faced with a health crisis that is unprecedented in contemporary history, requiring forced shutdowns to curb the spread of the virus, governments have taken urgent measures to prevent the onset of an uncontrolled crisis that could permanently alter the economic trajectory. Three main types of measures have been taken: some aim to maintain consumer purchasing power in the face of the shutdowns; others seek to preserve the production system by targeting business; and some are specific to the health sector. The quarterly national accounts, available at the end of the first half of the year, provide an update on the extent to which the disposable income of private agents has been preserved by fiscal policy at this stage of the Covid-19 crisis [2].

Fiscal policy has shot up Americans’ household

income and preserved Europeans’ income

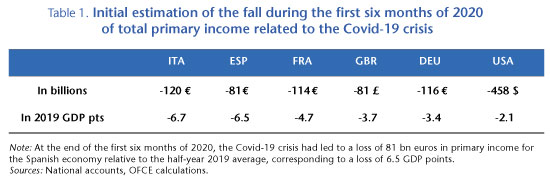

In the major advanced economies, the Covid-19

crisis generated losses in primary income (before cash transfers) ranging from 81

billion pounds in the United Kingdom to 458 billion dollars in the United

States (Table 1). The initial income shock was thus larger in Spain and Italy –

6.5 and 6.7 GDP points respectively – and smaller in Germany (3.4 GDP points)

and the United States (2.1 GDP points).

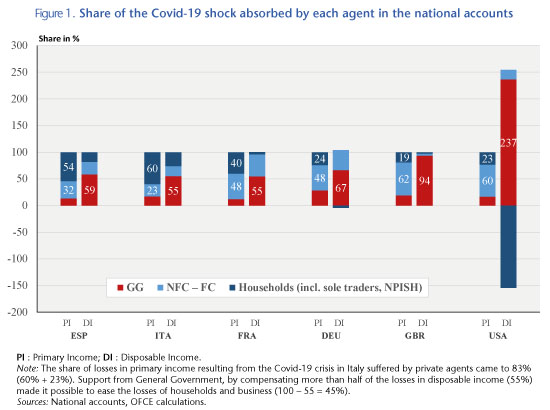

Figure 1 breaks down the share of the primary income (PI) shock received by agents (first bar on the left for each country, labelled “PI”). In Spain and Italy, households suffered the majority of the losses, accounting for 54 percent and 60 percent, respectively, of the total income loss for the economy. In France and Germany, enterprises bore the lion’s share of the income loss (48%). In the United Kingdom and the United States, enterprises incurred losses of £50 billion and $275 billion, respectively, accounting for 62% and 60% of the total loss for the economy. General government (GG) experienced a smaller shock in all the countries, which is explained by the spontaneous changes in some of the automatic stabilizers, and by a relatively lower value added due to the restrictions on activity during lockdowns.

Turning to the breakdown in losses in disposable

income (DI), which takes into account cash transfers, social contributions, and

income tax, the story is rather different. The implementation of emergency

measures made it possible to absorb some of these losses, as illustrated by the

bar labelled “DI” in Figure 1. The introduction of short-time working

in European countries thus shifted the burden of wages from enterprises to the

government, thus preserving household incomes and avoiding the termination of job

contracts. Similarly, reductions in social contributions and tax on income and

corporate profits have shifted the cost of the crisis from private agents to

government. In the face of the unforeseeable shock, the State has thus played

the role of insurer of last resort of private agent income, although to

different extents in different countries. Thus, while Spain’s government absorbed

13.5 percent of the primary income shock, support measures raised this share to

59 percent, a higher level than that of Italy (55.3 percent) and France (54.3

percent) in terms of disposable income. In comparison, the measures taken by

the German government absorbed a higher share of the shock, amounting to 67

percent of the loss of disposable income, compared with 28 percent of the fall in

primary income.

In the United Kingdom, emergency measures absorbed

the entirety of the shock. While business and households suffered primary

income losses of £50 billion and £15 billion respectively, their disposable

income fell by only £4 billion and £2 billion. As for disposable income,

government absorbed 93.6 percent of the shock. The contrast is even more marked

in Germany and the United States, where measures overcompensated the initial

primary income shock, especially for households. The US figures are

particularly impressive. Over the six-month period, primary income fell by $192

billion, while household disposable income rose by $576 billion, due in

particular to the payment of a tax credit and an exceptional federal

unemployment benefit of $600 per week that was paid to the unemployed,

regardless of their initial income[3]. The various tax measures and subsidies to

business reduced the loss by $210 billion. The US government thus absorbed 237

per cent of the shock, reflecting the magnitude of the support measures taken

in March-April.

Job losses and uncertainty about the future may

hamper recovery across the Atlantic

As we have seen, fiscal policy has been mobilized

massively across the Atlantic. Even if at this stage the macroeconomic shock has

been weaker in the US than in the EU[4], the fiscal impulse is much larger. At the end of

the first half-year, total transfers to households exceeded the immediate shock

to their primary income. This has led to a 13% increase in the disposable

income of US households, at the same time as their primary income fell by 4% in

connection with job destruction. This situation is due in particular to a tax credit

paid to households and an additional lump-sum allowance of $600 per week paid

by the federal government to any person eligible for unemployment. Between Q4 of

2019 and Q2 of 2020, transfers to households leapt by 80%, now representing 31%

of disposable income compared with 19% in 2019.

This difference in crisis management is undoubtedly

explained by the weakness of the social safety net in the United States, which

effectively reduces the role of automatic stabilizers while also limiting the

ability of citizens with little or no health insurance coverage to meet health

care expenses in the event of a fall in income. The use of counter-cyclical

measures is thus of greater importance, which probably explains why the

stimulus packages are more extensive than they were during the 2008-2009 crisis

as well as why the measures provide direct, substantial support to household

income. Moreover, in the US, the federal government is responsible for this

stimulus, while in the EU, the bulk of the support plans come from the Member states.

The sharp rise in unemployment across the Atlantic

– which peaked at 14.7% in April – contrasts with the situation in Europe,

partly due to the differentiated strategy in economic policy. The United States carried out a positive, substantial

transfer of income to households to offset the fall in wages resulting from job

losses, which also helped to mitigate the shock on business margins.

Conversely, in the main European economies, contractual employment

relationships were maintained, but household incomes were not preserved quite

as much – they actually fell slightly, except in Germany. In the main European

economies, a decision was taken to use short-time working on a massive scale, while

in the United States the response was to send cheques directly and immediately

to households.

This situation, where income was propped up during

a period when consumption was curtailed by the closure of non-essential shops, led

to the accumulation of 76 billion euros in “Covid savings” in Germany

(8 GDI points), 62 billion in France (9 GDI points) and 38 billion in Spain and

Italy (10 and 6 GDI points respectively). In the United Kingdom and the United

States, “Covid savings” were even greater: £89 billion in the UK (12 GDI

points), while the sum reached $961 billion in the US (12 GDI points). How the

epidemic develops and how these savings are used will be the two keys

determining the extent of the rebound in activity starting in the second half

of 2020.

This is precisely the moment when differences in

approach can create divergences in economic trajectories. While it could be

said that up to now household situations have been better preserved across the

Atlantic, job contracts have been shredded. In this context, it may take some

time to get the workforce back into employment, hindering the rapid

redeployment of the production base. This could slow down the speed at which activity

returns to normal, helping to keep job losses up and limiting the restoration

of company balance sheets. Furthermore, negotiations between Democrats and

Republicans in Congress have hit the wall of the approaching November 3

elections. If the measures taken during the crisis are not – at least partially

– renewed, the situation of American households is likely to become more

critical, since weak US social safety nets will not be able to mitigate what

threatens to be a long-term shock. This may have second-round effects on

primary income and investment [5]. Following the elections, further measures are

likely to be taken, but the time lag could be long, especially if Joe Biden

wins, as he will have to wait until he takes office in January 2021. Continued

high uncertainty about the extent of the recovery – accentuated by political

uncertainty – may encourage American households to avoid spending “Covid

savings” in order to have “precautionary savings” to face a probable

long-term health, economic and social crisis.

Glossary

Primary income (PI): Primary income includes revenue directly related

to participation in the production process. The bulk of primary household

income consists of wages, salaries and property income.

Gross disposable income (GDI): Income available to agents to consume or invest,

after redistribution operations. This includes primary income plus social cash

benefits and minus social contributions and taxes paid.

* * *

[1] See “Evaluation de la pandémie de Covid-19 sur

l’économie mondiale” [Evaluation

of the Covid-19 pandemic on the world economy], Revue de l’OFCE no. 166 for

an initial analysis of the various fiscal and monetary support measures

implemented.

[2] These results should be taken with a grain of

salt. While the quarterly national accounts are the most comprehensive,

consistent framework available, with data collected by official statistics

institutes, they are nevertheless provisional. These accounts are subject to

significant revisions that may significantly alter the final results when they

incorporate new data (company balance sheets, etc.); they are considered final

within two years.

[3] This allowance is in addition to that paid by

State-run unemployment insurance systems.

[4] The loss in 6-month GDP was 5% in the US,

compared with 8.3% in the EU.

[5] F. Buera, R. Fattal-Jaef, H. Hopenhayn, A.

Neumeyer, and J. Shin (2020), “The Economic Ripple Effects of COVID-19”, Working Paper.