By Maylis Avaro and Henri Sterdyniak

The European summit on 28th and 29th June marked a new attempt by Europe’s institutions and Member states to overcome the crisis in the euro zone. A so-called Growth Pact was adopted, but it consists mainly of commitments by the Member states to undertake structural reform, and the limited funds made available (120 billion over several years) were for the most part already planned. The strategy of imposing restrictive fiscal policies was not called into question, and France pledged to ratify the Fiscal Compact. The interventions of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) will now be less rigid, as, without additional conditions, they can help countries that the financial markets refuse to finance so long as they meet their objectives in terms of fiscal policy and structural reform. But euro-bonds and the mutual guarantee of public debt were postponed. The summit also launched a new project: a banking union. Is this an essential supplement to monetary union, or is it a new headlong rush into the unknown?

The current crisis is largely a banking crisis. The European banks had fed financial bubbles and housing bubbles (especially in Spain and Ireland), and they had invested in mutual funds and hedge funds in the United States. After major losses during the crisis of 2007-2010, the Member states came to their rescue, which was particularly costly for Germany, the UK, Spain and above all Ireland. The sovereign debt crisis in the euro zone has compounded their woes: the sovereign debt that they hold has become a risky asset. The problem of regulating the banks has been raised at the international level (new Basel III standards), in the United States (Volkers rule and Dodd-Frank law) and in Britain (Vickers report).

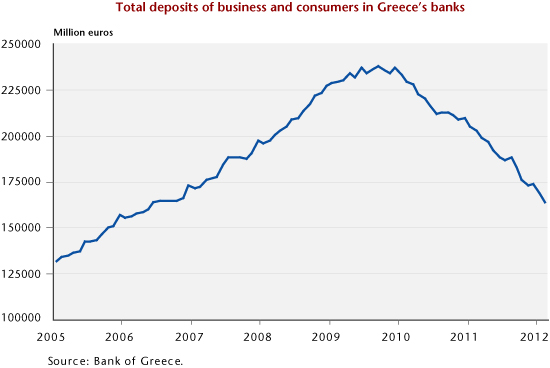

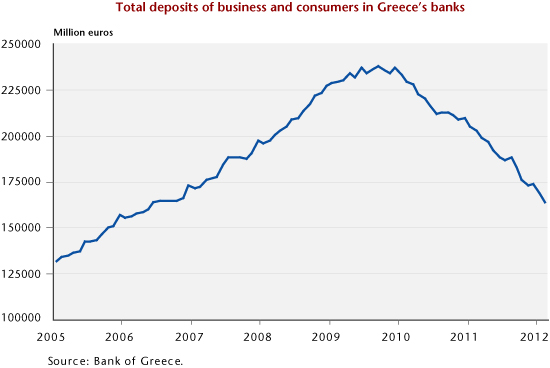

In June 2012, doubts about the soundness of Europe’s banks surfaced yet again. The measures taken since 2008 to stabilize the financial system have proved insufficient. When Bankia, Spain’s fourth-largest bank, announced that it was requesting State assistance of 19 billion euros, worries about the balance sheets of Spanish banks rose sharply. The rate of bad loans of the country’s banks, whose balance sheets were hit hard by the real estate crash, rose from 3.3% at end 2008 to 8.7% in June 2012 [1]. Furthermore, many Greeks, fearing an exit from the euro zone, began to reduce their deposits in the banks there [2].

In response to these dangers, the proposal for a European banking union was given a new boost by Mario Monti. Italy’s PM suggested developing the proposals in preparation for the European Commission Single Market DG, an idea that currently has the support of the Commission, the European Central Bank, and several Member states (Italy, France, Spain, etc.) On the other hand, Germany believes that a banking union is impossible without a fiscal union. While Angela Merkel acknowledged [3] that it was important to have a European supervisory authority, with a supranational banking authority with a better general overview, she clearly rejected the idea of Germany taking a risk of further transfers and guarantees without greater fiscal and policy integration [4]. The euro zone summit meeting on 29 June asked the Commission to make proposals shortly on a single monitoring mechanism for the euro zone’s banks.

This kind of banking union would rest on three cornerstones:

– a European authority in charge of centralized oversight of the banks,

– a European deposit guarantee fund,

– a common mechanism for resolving bank crises.

Each of these cornerstones suffers specific problems: some are related to the complex way the EU functions (Should a banking union be limited to the euro zone, or should it include all EU countries? Would it be a step towards greater federalism? How can it be reconciled with national prerogatives?), while others concern the structural choices that would be required to deal with the operations of the European banking system.

As to the institution that will exercise the new banking supervisory powers, the choice being debated is between the European Banking Authority (EBA) and the ECB. The EBA was established in November 2010 to improve oversight of the EU banking system, and it has already conducted two series of “stress tests” on the banks. As a result of the tests, in October 2011 Bankia reported a 1.3 billion euro shortage of funds. Five months later, the deficit was 23 billion; the EBA’s credibility suffered. In addition, the London-based EBA has authority over the British system, while the United Kingdom does not want to take part in the banking union. The ECB has, for its part, received support from Germany. Article 127.6 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union [5], which was cited at the euro zone summit of June 29th as a basis for the creation of a European Banking Authority, would make it possible to give the ECB supervisory authority. On 12 June, the Vice-President of the ECB, Mr. Constancio, said that, “the ECB and the Eurosystem are prepared” to receive these powers; “there is no need to create a new institution”.

European oversight implies a common vision of banking regulation. There must be agreement on crucial issues, such as: “Does commercial banking need to be separated from investment banking?” “Should banks be prohibited from operating on the financial markets for their own account?” “Should public or mutual or regional banks be encouraged rather than large internationalized banks?” “Should banks be encouraged to extend credit primarily to businesses and government in their own country, or on the contrary to diversify?” “Should the macro-prudential rules be national or European?” In our opinion, entrusting these matters to the ECB runs the risk of taking a further step in the depoliticization of Europe.

Applying the guidelines of this new authority will be problematic. A banking group in difficulty could be ordered to divest its holdings in large national groups. But would a country’s government expose a national champion to foreign control? Governments would lose the ability to influence the distribution of credit by banks, which some people might find desirable (no political interference in lending), but in our opinion is dangerous (governments would lose a tool of industrial policy that could be used to finance Small and Medium Enterprises [SMEs] and Economic and technological intelligence [ETI] projects or to support the ecological transition).

For example, in a case involving Dexia, the opposition between the European Commission on the one hand and France, Belgium and Luxembourg on the other is blocking a restructuring plan. The plan includes the takeover of Dexia Credit Local’s financing of local authorities by a banking collectivity that would be created based on cooperation between La Banque postale and the Caisse des depots. In the name of fair competition, Brussels is challenging the financing of local communities by such a bank, as Dexia has received public funding for its restructuring plan. This is threatening the continuity of the financing of the French local authorities, and could put a halt to their plans; in particular, it could prevent France from providing specific secure mechanisms for financing local authorities through local savings.

The purpose of a deposit guarantee fund is to reduce the risk of a massive withdrawal of deposits during a banking panic. This fund could be financed through contributions by the European banks guaranteed by the fund. According to Schoenmaker and Gros [6], a banking union must be created under a “veil of ignorance”, that is to say, without knowing which country poses the greatest risk: this is not the case in Europe today. The authors propose a guarantee fund that at the outset would accept only the strongest large transnational banks, but this would immediately heighten the risk of the zone breaking apart if depositors rushed to the guaranteed banks. The fund would thus need to guarantee all Europe’s banks. According to Schoenmaker and Gros, assuming a 100,000 euro ceiling on the guarantee, the amount of deposits covered would be 9,700 billion euros. The authors argue that the fund should have a permanent reserve representing 1.5% of the deposits covered (i.e. about 140 billion euros). But this would make it possible to rescue only one or two major European banks. During a banking crisis, amidst the risk of contagion, such a fund would have little credibility. The guarantee of deposits would continue to depend on the States and on the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), which would have to provide support funds, ultimately by requiring additional contributions from the banks.

The authority in charge of this fund has not yet been designated. While the ECB appears well positioned to undertake supervision of the banking system, entrusting it with management of the deposit guarantee fund is much more problematic. According to Repullo [7], deposit insurance should be separated from the function of lender of last resort. Indeed, otherwise the ECB could use its ability to create money to recapitalize the banks, which would increase the money supply. The objectives of monetary policy and of support for the banks would thus come into conflict. What is needed is a body that handles deposit insurance and crisis resolution and is separate from the ECB, and which must have a say on the behavior of the banks, and which would be additional to the EBA, the ECB, and the national regulators. The ECB on the other hand would continue to play its role as lender of last resort. But it is difficult to see how such a complicated system would be viable.

As the risk of a country leaving the euro zone cannot yet be dismissed, the question arises as to what guarantee would be offered by a banking union in the case of a conversion into national currency of euro-denominated deposits. A guarantee of deposits in the national currency would, in the case of an exit from the euro, heavily penalize customers of banks that suffer a devaluation of the national currency against the euro, whose purchasing power would decline sharply. This kind of guarantee does not solve the problem of capital flight being experienced today by countries threatened by a risk of default. What is needed is a guarantee of deposits in euros, but in today’s situation, given the level of risk facing some countries, this is difficult to set up.

German and Finnish politicians and economists such as H. W. Sinn are, for instance, denouncing an excessive level of risk for Germany and the Nordic countries. According to several German economists, no supranational authority has the right to impose new burdens (or risk levels) on the German banks without the consent of Parliament, and the risk levels need to be explicitly limited. The German Constitutional Court might oppose the deposit guarantee fund as exposing Germany to an unlimited level of risk. Moreover, according to George Osborne, the Chancellor of the British Exchequer, a bank deposit guarantee at the European level would require an amendment to existing treaties and the consent of Great Britain.

On 6 June, the European Commission began to develop a common framework for resolving banking crises by adopting the proposal of Michel Barnier, which has three components. The first is to improve prevention by requiring banks to set up testaments, that is, to provide for recovery strategies and even disposal plans in case of a serious crisis. The second gives the European banking authorities the power to intervene to implement the recovery plans and to change the leadership of a bank if it fails to meet capital requirements. The third provides that, if a bank fails, the national governments must take control of the establishment and use resolution tools such as divestiture, the creation of a defeasance bank, or “bad” bank, or an internal bailout (by forcing shareholders and creditors to provide new money). If necessary, the banks could receive funds from the ESM. Bank-related risks would therefore be better distributed: the shareholders and creditors not covered by the guarantee would be first to be called upon, so that the taxpayers would not pay to reimburse the creditors of insolvent banks. In return, bank loans and shares would become much riskier; bank reluctance about inter-bank credit and the drying up of the interbank market due to the crisis would persist; and the banks would find it difficult to issue securities and would have to raise the level of compensation. However, Basel III standards require banks to link their lending to the level of their capital. This would pose a risk of constraining the distribution of credit, thereby helping to keep the zone in recession. Based on the decisions of the summit on 29 June, Spain could be the first country whose banks would be recapitalized directly by the ESM. However, this would not take place until early 2013; the terms of the procedure and the impact of ESM aid on the governance of the recapitalized banks still need to be determined. As can be seen in the Dexia example, what terms are set for the reorganization of a bank can have serious consequences for the country concerned: are governments (and citizens) willing to lose all power in this domain?

A banking union can help break the correlation between a sovereign debt crisis and a banking crisis. When the rating agencies downgrade a country’s debt, the securities suffer a loss in value and move into the category of “risky assets”, becoming less liquid. This increases the overall risk faced by the banks in the country concerned. If a bank is facing too much overall risk and it is no longer able to meet the capital requirements of Basel III, the State must recapitalize it, but to do this it must take on debt, thereby increasing the risk of a default. This link between the banks’ fragile balance sheets and public debt generates a dangerous spiral. For instance, since the announcement of the bankruptcy of Bankia, Spain’s 10-year refinancing rates reached the critical threshold of 7%, whereas last year the rates were about 5.5%. In a banking union, the banks would be encouraged to diversify on a European scale. However, the crisis of 2007-09 demonstrated the risks of international diversification: many European banks lost a great deal of money in the US; foreign banks are unfamiliar with the local business scene, including SMEs, ETIs and local government. Diversification based on financial criteria does not fit well with a wise distribution of credit. Moreover, since the crisis, European banks are tending to retreat to their home countries.

The proposal for a banking union assumes that the solvency of the banks depends primarily on their own capital, and thus on the market’s evaluation, and that the links between a country’s needs for financing (government, business and consumers) and the national banks are severed. There is an argument for the opposite strategy: a restructuring of the banking sector, where the commercial banks focus on their core business (local lending, based on detailed expertise, to businesses, consumers and national government), where their solvency would be guaranteed by a prohibition against certain risky or speculative transactions.

Would banking union promote further financialization, or would it mark a healthy return to the Rhineland model? Would it require the separation of commercial banks and investment banks? Would it mean prohibiting banks whose deposits are guaranteed to do business on the financial markets for their own account?

[1] According to the Bank of Spain.

[2] The total bank accounts of consumers and business fell by 65 billion in Greece since 2010. Source: Greek Central Bank.

[3] “La supervision bancaire européenne s’annonce politiquement sensible”, Les Echos Finance, Thursday 14 June 2012, p. 28.

[4] “Les lignes de fracture entre Européens avant le sommet de Bruxelles”, AFP Infos Economiques 27 June 2012.

[5] Art 127.6: ”The Council, acting by means of regulations in accordance with a special legislative procedure, may unanimously, and after consulting the European Parliament and the European Central Bank, confer specific tasks upon the European Central Bank concerning policies relating to the prudential supervision of credit institutions and other financial institutions with the exception of insurance undertakings.”

[6] D. Schoenmaker and Daniel Gros (2012), “A European Deposit Insurance and Resolution Fund”, CEPS working document, No. 364, May.

[7] Repullo, R. (2000), “Who Should Act as Lender of Last Resort? An Incomplete Contracts Model”, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 32, 580-605.