Does too much finance kill growth?

By Jérôme Creel, Paul Hubert and Fabien Labondance

Is there an optimal level of financialization in an economy? An IMF working paper written by Arcand, Berkes and Panizza (2012) focuses on this issue and attempts to assess this level empirically. The paper highlights the negative effects caused by excessive financialization.

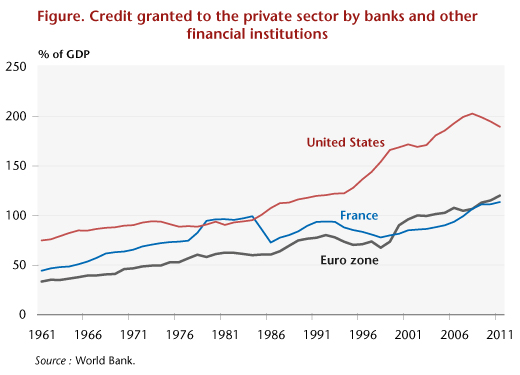

Financialization refers to the role played by financial services in an economy, and therefore the level of indebtedness of economic agents. The indicator of the level of financialization is conventionally measured by calculating the ratio of private sector credit to GDP. Until the early 2000s, this indicator took into account only the loans granted by deposit banks, but the development of shadow banking (Bakk-Simon et al., 2012) has been based on the credit granted by all financial institutions. This indicator helps us to understand financial intermediation (Beck et al., 1999) [1]. The graph below shows how financialization has evolved in the euro zone, France and the United States since the 1960s. The level has more than doubled in these three economies. Before the outbreak of the subprime crisis in the summer of 2007, loans to the private sector exceeded 100% of GDP in the euro zone and 200% in the United States.

Arcand, Berkes and Panizza (2012) examined the extent to which the increasingly predominant role played by finance has an impact on economic growth. To understand the importance of this paper, it is useful to recall the existing differences in the findings of the empirical literature. On the one hand, until recently the most prolific literature highlighted a positive causal relationship between financial development and economic growth (Rajan and Zingales, 1998, and Levine, 2005): the financial sector acts as a lubricant for the economy, ensuring a smoother allocation of resources and the emergence of innovative firms. These lessons were derived from models of growth (especially endogenous) and have been confirmed by international comparisons, in particular with regard to developing countries with small financial sectors.

Some more skeptical authors believe that the link between finance and economic growth is exaggerated (Rodrik and Subramanian, 2009). De Gregorio and Guidotti (1995) argue that the link is tenuous or even non-existent in the developed countries and suggest that once a certain level of economic wealth has been reached, the financial sector makes only a marginal contribution to the efficiency of investment. It abandons its role as a facilitator of economic growth in order to focus on its own growth (Beck, 2012). This generates major banking and financial groups that are “too big to fail”, enabling these entities to take excessive risks since they know they are covered by the public authorities. Their fragility is then rapidly transmitted to other corporations and to the economy as a whole. The subprime crisis clearly showed the power and magnitude of the effects of correlation and contagion.

In an attempt to reconcile these two schools of thought, a nonlinear relationship between financialization and economic growth has been posited by a number of studies, including in particular the Arcand, Berkes and Panizza (2012) study. Using a dynamic panel methodology, they explain per capita GDP growth by means of the usual variables of endogenous growth theory (i.e. the initial GDP per capita, the accumulation of human capital over the average years of education, government spending, trade openness and inflation) and then add to their model credit to the private sector and the square of this same variable in order to take account of potential non-linearity. They are thus able to show that:

- The relationship between economic growth and private sector credit is positive;

- The relationship between economic growth and the square of private sector credit (that is to say, the effect of credit to the private sector when it is at a high level) is negative;

- Taken together, these two factors indicate a concave relationship – a bell curve – between economic growth and credit to the private sector.

The relationship between finance and growth is thus positive up to a certain level of financialization, and beyond this threshold the effects of financialization gradually start to become negative. According to the different specifications estimated by Arcand, Berkes and Panizza (2012), this threshold (as a percentage of GDP) lies between 80% and 100% of the level of loans to the private sector. [2]

While the level of financialization in the developed economies is above these thresholds, these conclusions point to the marginal gain in efficiency that financialization can have on an economy and the need to control its development. Furthermore, the argument of various banking lobbies, i.e. that regulating the size and growth of the financial sector would negatively impact the growth of the economies in question, is not supported by the data in the case of the developed countries.

[1] While this indicator may seem succinct as it does not take account of disintermediation, its use is justified by its availability at international level, which allows comparisons. Furthermore, more extensive lessons could be drawn with a protean indicator of financialization.

[2] Cecchetti and Kharroubi (2012) clarify that these thresholds should not be viewed as targets, but more like “extrema” that should be reached only in times of crisis. In “normal” times, it would be better that debt levels are lower so as to give the economies some maneuvering room in times of crisis.