By Eric Heyer

Did the Aubry laws introducing the 35-hour work week in France between 1998 and 2002 really make French business less competitive and lead to job losses, as is suggested in the latest report from the OECD? Has France seen its economic performance decline post-reform relative to its European partners? Have the public finances been “weighed down” by these laws?

A review of our recent macroeconomic history, coupled with international comparisons, provides some answers to these questions.

Record macroeconomic performances in the private sector between 1998 and 2002…

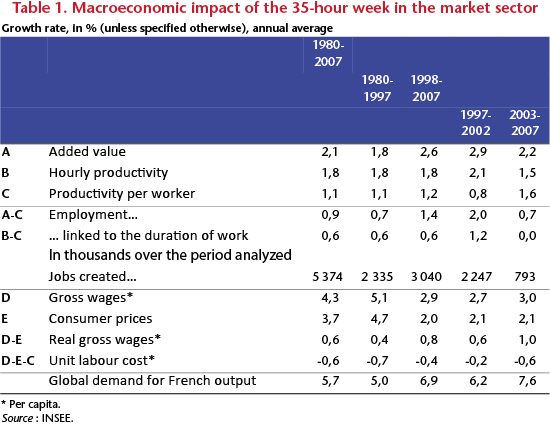

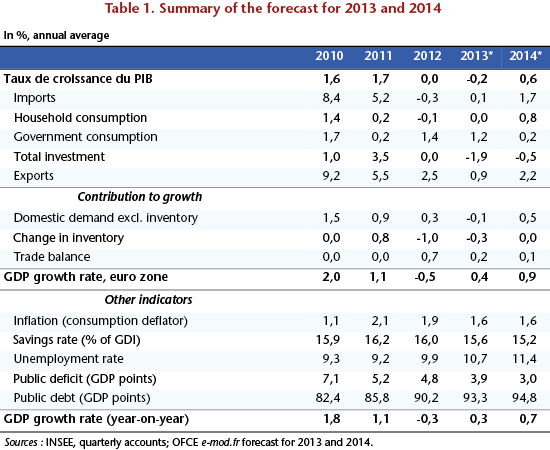

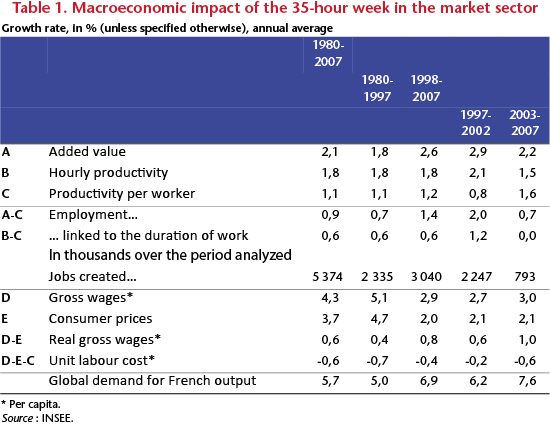

Leaving aside an analysis of the recent Great Recession, over the past 30 years private sector activity in France grew by an annual average of 2.1%. Since the establishment of the 35‑hour work week, far from collapsing, economic growth in this sector instead accelerated sharply, from 1.8% before 1997 to 2.6% afterwards, and even hit a peak during the period in which the 35-hour week was being established (an annual average of 2.9%, Table 1). Furthermore, it is noteworthy that of the five best years recorded by the French market sector over the past 30 years, three were in the period 1998-2002 based on the criterion of GDP growth, and four if the criterion used is job creation.

The global economic environment accounts for some of this good performance, but only in part: foreign demand for French output was certainly more dynamic after 1997 than before, but this acceleration continued after 2002, and cannot therefore explain the better performances recorded between 1998 and 2002 (Table 1).

… and better than the performance of our European partners

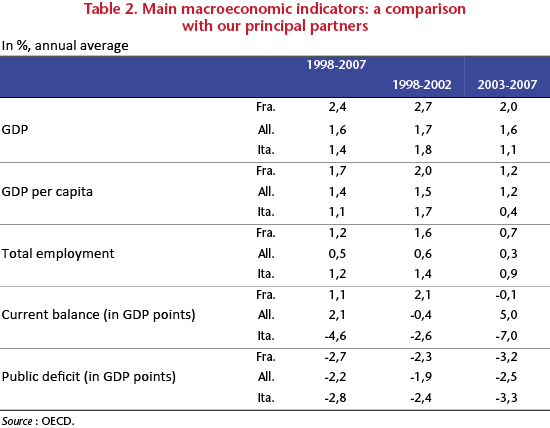

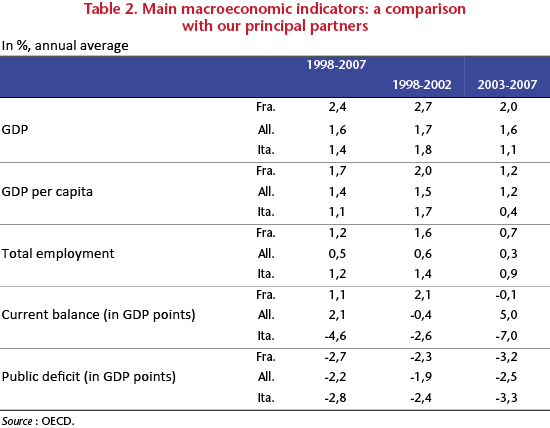

Since the establishment of the 35-hour work week, France’s performance has been superior to that of the rest of the euro zone, especially in comparison with our two main partners, Germany and Italy. For instance, over the decade 1998-2007 France’s average annual growth was 1 point higher than for Italy and 0.8 point than for Germany (Table 2).

During this period, French companies and households spent more than their German and Italian counterparts. Business investment, which rose at an annual average of 0.8%, was more dynamic in France than in Germany (0.3%) or Italy (0.5%). As for households, consumption grew by an annual average of 1.4% in France against, respectively, 0.4% in Germany and 0.9% in Italy. Furthermore, it should be noted that the continued higher consumption in France does not reflect the behaviour of household savings. The savings rate was not only higher than elsewhere in Europe, but it has also risen since 1998. The solid performance of French consumption is the consequence of greater dynamism in job creation in France during this period, especially when compared to what was taking place in Germany (Table 2).

Unit labour costs [1] under control

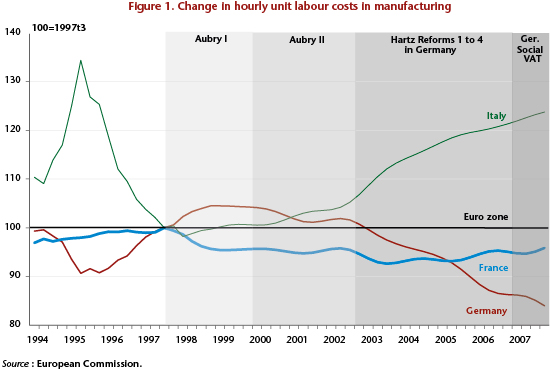

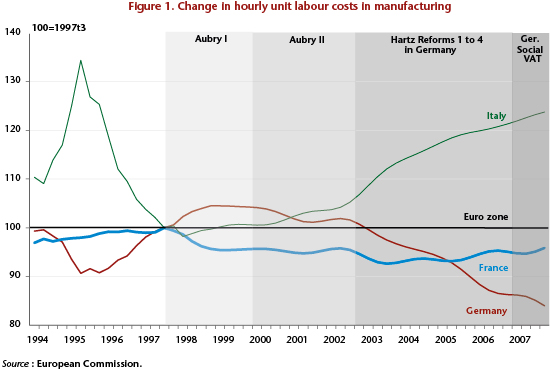

Considering the large countries, France has cut hourly unit labour costs in the manufacturing sector the most during the period 1997-2002 (Figure 1). With respect to labour costs for the economy as a whole, only Germany has done better than France over this period.

The implementation of the Aubry laws has not therefore led to reducing the competitiveness of the French economy. The reasons why are now well known: the way the increase in hourly wages linked to the 35-hour week was offset by wage moderation; the more flexible organization of working time, which helped to boost the hourly productivity of labour (Table 1); the suppression of overtime pay; and finally State aid in the form of lower social contributions.

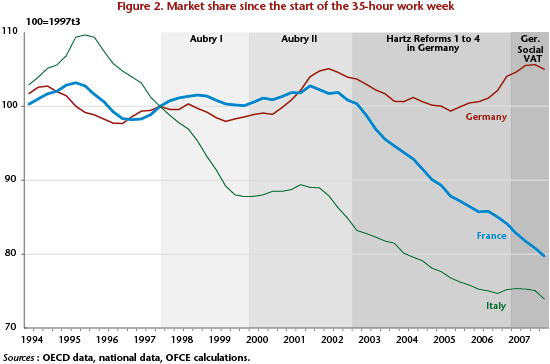

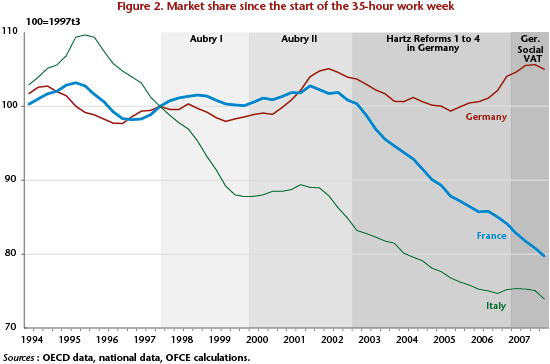

Between 1997 and 2002 , by better controlling wage costs than most European and Anglo-American countries, France improved its price competitiveness and thereby its market share of world trade (Figure 2). The share of French exports in world trade, which was helped by the weakness of the euro and by wage moderation, reached a peak in 2001.

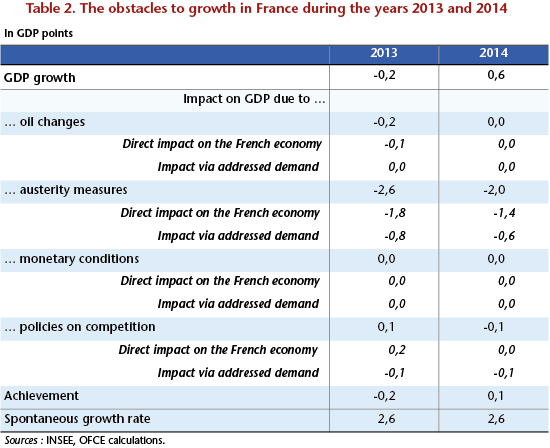

Since 2002, France’s market share has declined considerably, for two basic reasons: first, the loss of price competitiveness of French exports subsequent to the appreciation of the nominal effective exchange rate in France, comparable to that observed in the early 1990s, and second, Germany’s commitment to a policy of drastically reducing production costs. Since 2002, Germany has engaged in a process of improving its supply by restricting income and social transfers ( Hartz reforms , social VAT), which led to lower unit labour costs in absolute terms but also relative to its other European partners, including France. It is this policy that accounts for the 30% loss in market share experienced by France in the period 2002-2007.

The loss in market share is thus not peculiar to France. The policy being implemented in Germany has enabled it to gain market share in countries that are geographically and structurally close to it, i.e. the large European countries. In this respect, France is not the only country to have suffered from this strategy, as Italy too has lost market share during this period[2].

In total, since the introduction of the 35-hour week, Italy has lost even more market share than the French economy (-27% for Italy against -20% for France).

A limited cost for the public purse

Since the implementation of the Aubry laws, the relief on charges on low wages has cost general government an annual average of nearly 22 billion euros. But this amount is not attributable solely to the Aubry laws, since even before that such measures had been established by the Balladur and Juppé governments in the early and mid 1990s. The additional relief generated by the Aubry laws, which was made more long term by the “Fillon” measures, comes to nearly 12.5 billion euros per year. But this amount does not represent the cost actually incurred by general government. Indeed, as the Aubry laws have created jobs (350,000 over the period 1997-2002 according to official figures by the DARES and used by the INSEE), the cost for the public purse has been smaller: this job creation generates four billion euros in additional payroll taxes; this has reduced the number of unemployed, and thus unemployment benefits by 1.8 billion euros; and finally this has boosted household income, and the consequent consumption is generating additional tax revenues (VAT, income tax, etc.) in the amount of 3.7 billion euros. In sum, once the macroeconomic feedback is taken into account, the additional cost of these reductions comes to 3 billion euros annually, or 0.15 percentage point of GDP.

A review of our macroeconomic history does not therefore corroborate the thesis that the 35-hour week has “weighed down” the French economy: business growth and job creation were higher during the period from 1997 to 2007 than in the rest of the euro zone, and the competitiveness of the French economy, as measured by unit labour costs, fell by less than in the rest of the euro zone, with the exception of Germany. In this regard, it appears that the strategy conducted in Germany from 2002 (Hartz reform and social VAT) better explains the losses in market share by both the French economy and our other European partners. It is rather in the public sector, including hospitals, that the 35-hour work week has proven ineffective.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

The different measures relaxing the 35-hour week

I –The Fillon law of 2003

The Law of 17 January 2003 has two main provisions:

(1) Regulation of overtime

By increasing the overtime quota from 130 to 180 hours, this law permits companies to use overtime structurally. Allowing for an additional 4 hours per week throughout the year enables companies to stay on a 39-hour week if they so wish. Specific industries also have the right to negotiate a higher amount. The Decree of 9 December 2004 brought the regulatory overtime quota to 220 hours per year.

The Law also reduces the cost of overtime. For companies with 20 employees or fewer, overtime begins only with the 37th hour, and the rate of extra pay is only 10%. For other firms, this may be negotiated between 10% and 25% by an industry agreement.

(2) Measure easing social contributions

The provisions for the reduction of employer social contributions introduced by the Aubry laws were henceforth disconnected from the length of the work week. All companies, whether or not they had shifted to the 35-hour week, now benefited. Structural aid beyond 1.6 times the minimum wage (SMIC) was eliminated.

II – The tax exemption of overtime hours in 2007

This measure had several provisions:

(1) Lump-sum reduction in payroll taxes

This measure introduced a lump-sum reduction in payroll taxes of 1.5 euros per hour of overtime worked by companies with fewer than 20 employees and 0.50 euros in enterprises with more than 20 employees.

(2) Alignment of extra pay for overtime

This measure provided that extra pay for overtime be aligned at the minimum rate of 25% for all companies.

(3) Exemption from income tax

This measure allowed employees to exempt their pay for overtime hours from income tax, up to a limit of 25% extra.

(4) Exemption from social contributions

This measure also included a reduction of payroll taxes equal to the amount of the CSG / CRDS tax as well as all legal and contractual contributions.

______________________________________________________________________________

For more information:

Philippe Askenazy, Catherine Bloch-London and Muriel Roger, 2004, “La réduction du temps de travail 1997-2003: dynamique de construction des lois ‘Aubry’ et premières evaluations” [The reduction of the work week 1997-2003: dynamics of the development of the Aubry laws and initial evaluations], Economie et Statistiques, no. 376-377.

Chen R., GM. Milesi-Ferreti and T. Tressel, 2013, “Eurozone external imbalances”, Economic Policy, 28 (73), pp. 102-142.

DARES, 2003, Les politiques de l’emploi et du marché du travail, Collection Repères, Editions La Découverte.

Guillaume Duval, 2008, Sommes-nous des paresseux ? et 30 autres questions sur la France et les Français, Editions du Seuil.

Alain Gubian, Stéphane Jugnot, Frédéric Lerais and Vladimir Passeron, 2004, “Les effets de la RTT sur l’emploi: des simulations ex-ante aux évaluations ex-post” [Impact of the shorter work week on employment: from ex-ante simulations to ex-post evaluations], Economie et Statistiques, n° 376-377.

Éric Heyer and Xavier Timbeau, 2000, “35 heures : réduction réduite” [35 hours: the reduction reduced], Revue de l’OFCE, no. 74, July.

[1] The unit labour cost is the ratio of the hourly cost of labour to the hourly productivity of the work.

[2] Other factors may of course explain Germany’s better performance, such as the emergence of China. For a recent version of this idea, see Chen R., G.M. Milesi-Ferreti and T. Tressel (2013).