Why can’t Greece get out of debt?

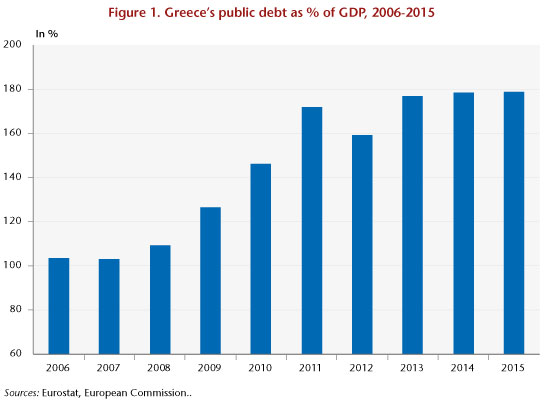

Between 2007 and 2015, Greece’s public debt rose from 103% to 179% [1] of its GDP (see chart below). The debt-to-GDP ratio rose at an uninterrupted pace, except for a 12-point fall in 2012 following the restructuring imposed on private creditors, and despite the implementation of two macroeconomic adjustment programs (and the beginning of a third) that were aimed precisely at redressing the Greek government’s accounts. Austerity has plunged the country into a recessionary and deflationary spiral, making it difficult if not impossible to reduce the debt. The question of a further restructuring is now sharply posed.

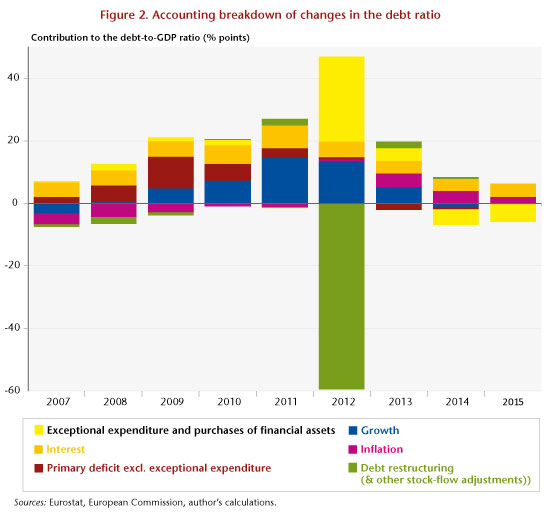

What explains this failure? How much have the various factors involved (public deficit, austerity, deflation, restructuring, bank recapitalization, etc.) contributed to changes in the debt? To provide some answers, we conducted an accounting breakdown of the changes in the debt ratio: the result is given in the graph below for the period 2007-2015.

Several phases, which correspond to various developments in the Greek crisis, are clearly identifiable on the chart.

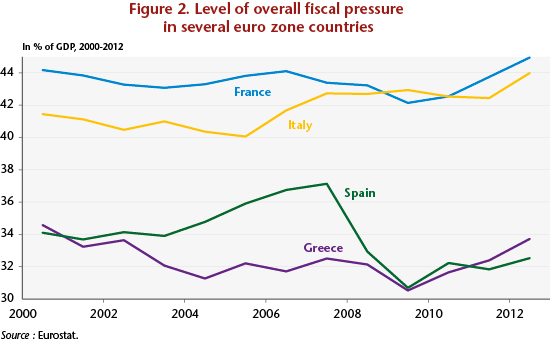

In 2007, prior to the financial storm, the GDP-to-debt ratio was stable: the negative effect of the budget deficit (including interest), which increases the ratio’s numerator, was offset by the positive impact of growth and inflation, which increase the denominator. So the situation was stable, at least temporarily, even though the debt level was already high (103% of GDP, which also explains the significant interest burden).

This stability was upset with the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009: growth disappeared and even entered negative territory, while the primary deficit was rising, partly due to the “automatic stabilizers”, and by 2009 came to 10 percentage points of GDP.

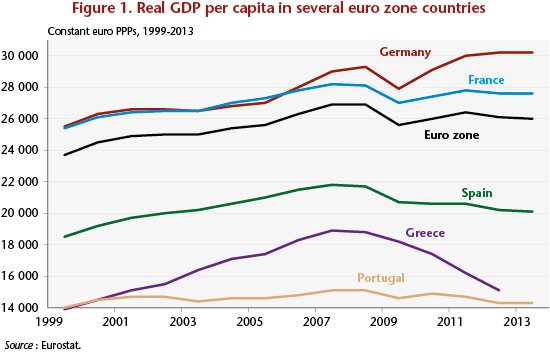

Given the intensity of the fiscal crisis, an initial adjustment plan was implemented in 2010. As the austerity measures began to bite, the primary deficit began to fall (to almost zero in 2012, excluding extraordinary expenses). But austerity also resulted in intensifying the recession: in 2011, growth (very negative) contributed nearly 15 GDP points to the increase in debt. Austerity also led to reducing inflation, which dropped to almost zero, and which is therefore no longer playing its natural role of cushioning debt. Meanwhile, the interest burden remained high (rising to 7.2 GDP points in 2011).

It should be recalled that the accounting breakdown presented here tends to underestimate the negative impact of growth and to overestimate the impact of the budget deficit. Indeed, a recession generates a cyclical deficit, through the automatic stabilizers, and therefore indirectly contributes to debt through the channel of the budget balance. However, to identify the structural and cyclical components of the budget deficit, an estimate of potential growth is needed. In the Greek case, given the depth of the crisis, this exercise is quite challenging, and the few estimates available diverge considerably; for this reason, we preferred to stick to a purely accounting approach.

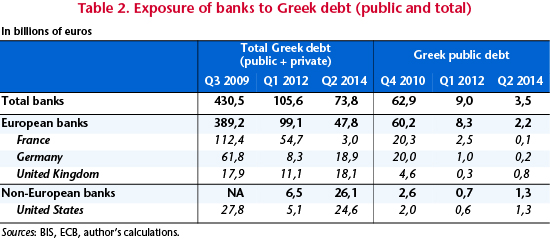

2012 was a year for big manoeuvres, with two successive debt restructurings in March and December. On paper, there was a substantial cancellation of debt (measured in terms of the stock-flow adjustment): almost 60 GDP points. But what should have been a significant reduction was largely offset by opposing forces. The recession remained exceptionally intense and accounted for 13.5 GDP points of the increase in debt. Above all, the main negative effect came from bank recapitalizations, which were necessitated by the writing off of public debt securities, which were largely held by domestic banks. In accounting terms, these recapitalisations take two forms: grants to banks (recorded as extraordinary expenses) or purchases of newly issued shares (recorded as purchases of financial assets) [2], which is why these two categories are grouped on the graphic. The category of purchases of financial assets also recognizes the establishment of a financial cushion to finance future bank recapitalizations [3].

In 2013, the debt-to-GDP ratio once again rose sharply, even though the primary balance (excluding exceptional expenses) showed a surplus. Bank recapitalizations (19 billion euros) were a heavy burden and were only partially covered by the sale of financial assets. The recession, although less intense, and deflation, now well established, made the picture even gloomier.

In 2014 and 2015, the situation improved, but without leading to any decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio, even though the primary deficit excluding exceptional spending was almost zero. Deflation persisted, while growth failed to restart (the 2014 upturn was moderate and short-lived), and the banks had to be recapitalized again in 2015 (for 5 billion euros). The interest burden remained high, despite the decision of the European creditors to lower rates on the loans from the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF): several years would be needed before this shows up in the effective interest burden. Only the sales of financial assets made it possible to hold down the increase in debt, which is clearly not sustainable in the long run since there is a limited stock of these assets.

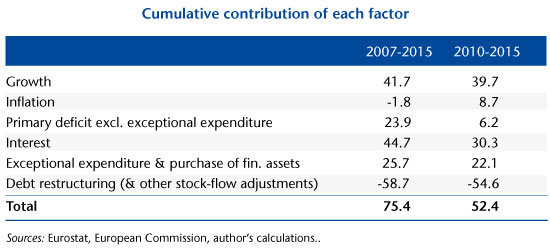

The table below shows the cumulative contribution of each factor for the period as a whole, and for the sub-period during which Greece was under programme (2010-2015).

The two main contributors to the increase in debt are growth (negative) and the cost of interest. In other words, the total increase in debt is due primarily to a “snowball effect”, which means the automatic increase due to the differential between the real interest rate and growth (the infamous “r-g”). The debt forgiveness in 2012 was not even sufficient to offset the snowball effect accumulated over the period. The bank recapitalizations that became necessary due in particular to the cancellation of debt were a heavy burden. The primary deficit, which is under the more direct control of the Greek government, comes only in 4th position from 2007 to 2015 (and doesn’t contribute much at all over the period 2010-2015).

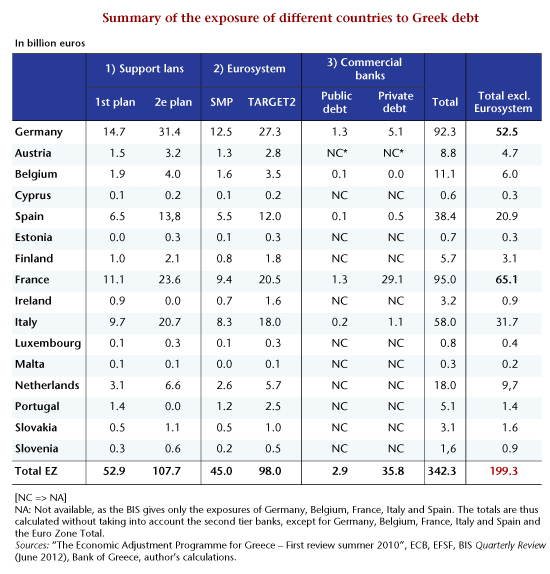

It is therefore clear that the sharp rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio since 2007 (and especially since 2010) was not primarily the result of the Greek government’s fiscal irresponsibility, but resulted instead from an erroneous consolidation strategy that was based on a logic of accounting austerity and not on coherent macroeconomic reasoning. An upturn in growth and inflation will be necessary to achieve any substantial debt reduction. But the new austerity measures set out in the third adjustment plan could cause a return to recession, while the constraints of price competitiveness within the euro zone make it impossible to foresee any renewal of inflation. A significant reduction of debt that is not conditional on a new destructive phase of austerity would allow a fresh start; in a previous study[4], we showed that a restructuring that cut Greece’s debt to 100% of its GDP would correspond to a sustainable scenario. However, Europe’s member states, which are now Greece’s main creditors, are currently rejecting such a scenario. The path to reducing Greek debt now looks more uncertain than ever…

[1] The data for 2015 are not yet fully available. The figures quoted for this year are projections by the European Commission published on 4 February 2016.

[2] These holdings in bank capital are recorded here at their purchase value. Any subsequent deterioration in these holdings is not reflected in the chart, because this would not lead to a further increase in the gross debt (although it would increase the net debt).

[3] In 2012, Greece bought 41 billion euros worth of EFSF bonds. Of this total, 6.5 billion were immediately given to the Bank of Piraeus, while 24 billion were lent to 4 big banks (which benefited from partial cancellation of their debt in 2013 against equity participations by the Greek State for a lesser value). The remaining 10 billion were returned unused by Greece to the EFSF in 2015, following the agreement of the Eurogroup on 22 February.

[4] See Céline Antonin, Raul Sampognaro, Xavier Timbeau and Sébastien Villemot, 2015, “La Grèce sur la corde raide” [Greece on the tightrope], Revue de l’OFCE, no. 138.