From the suburbs of London to global conflagration: a brief history of emissions

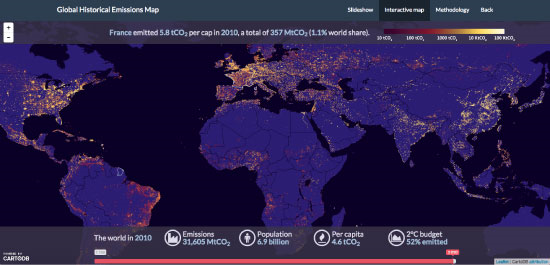

A new interactive map of global CO2 emissions from 1750 to 2010 is helpful in understanding the historical responsibilities of the world’s different regions for the climate crisis.

The 21st Conference of Parties (COP 21) ended on 12 December 2015 with a historic agreement. As 195 countries come to an accord on the need to limit global warming to 2 degrees by the end of the century, it is a good time to review the history of CO2 emissions since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Right to the end of the negotiations, the question of the historical responsibility of the different countries has remained one of the main obstacles blocking the path to a global climate agreement. The recently industrialized emerging countries and the developing countries that are just beginning their economic take-off rightly refuse to provide efforts comparable to those of the developed countries.

This feeling is confirmed by a new interactive map retracing 260 years of CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and cement production on the surface of the planet[1]. This map can be used interactively to explore the emissions of each country and their distribution in space over the last two centuries, both in their entirety and per capita. It can also be used to follow trends in global emissions and the gradual consumption of the total carbon budget for holding global warming to below 2 degrees.

By combining historical data on emissions per country issued by the CDIAC (from 1750-2010) with decadal data on population density produced by the European HYDE project (also 1750-2010), it is possible to estimate the distribution of emissions over space and time around the planet’s surface – on a grid with a resolution of 5’ of arc (5′ being equal to 1/12th of a degree, i.e. about 10 km by 10 km at the equator).

This interactive map shows the contribution of each of the world’s regions since the mid-18th century – while at the same time offering a gripping account of the gradual spread of the industrial revolution over the last two centuries.

These data illustrate several key points that help to understand the debate about differentiated historical responsibilities:

– Up to the mid-20th century, only Europe and the United States (and to a lesser extent Japan) contributed significantly to global emissions.

– It was only in the last 30 years that, led by China, the rest of the world “turned on”.

– Driven by rapid economic growth in the emerging countries, emissions have taken off in the last fifteen years.

– When weighted by distribution of the world population, emissions are highly concentrated spatially. This conclusion is bolstered when using even finer data, notably the location of power stations and the most energy-consuming manufacturing plants (cement, aluminium, and paper, for example).

This brief history of CO2 emissions across the globe reminds us of the West’s special responsibility in the fight against global warming. The precocity of the Industrial Revolution in the West allowed the economy to take-off much earlier than in the rest of the world, but it also led to the emission of a disproportionate share of the total emissions budget that we are entitled to if we are not to exceed the target of two degrees of warming.

This differentiated historical responsibility, which was recognized by the Paris Agreement, requires Western countries to make a special effort in the fight against global warming. This responsibility must thus be reflected in a greater effort in terms of financial and technological transfers so as to ensure that the emergence of the developing countries minimizes the use of fossil fuels, without hindering their economic take-off.

[1] These emissions do not include emissions from changes in land use (LUCLUF) or fertilizer use. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to reconstruct these emissions for the period under consideration.