Lower taxation on business but higher on households

By Mathieu Plane and Raul Sampognaro

Following the delivery of the Gallois Report in November 2012, the government decided at the beginning of Francois Hollande’s five-year term to give priority to reducing the tax burden on business. But since 2015, the President of the Republic seems to have entered a new phase of his term by pursuing the objective of reducing the tax burden on households. This was seen in the elimination of the lowest income tax bracket and the development of a new allowance mechanism that mitigates tax progressivity at the lower levels of income tax. But more broadly, what can be said about the evolution of the compulsory tax burden on households and businesses in 2015 and 2016, as well as over the longer term?

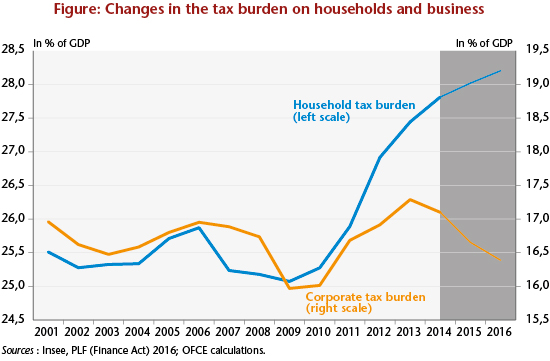

Based on data provided by the INSEE, we have broken down trends in the tax burden since 2001, distinguishing between levies on companies and those on households (Figure). While this is purely an accounting analysis and is not based on the final fiscal impact, it nonetheless gives a view of the breakdown of the tax burden[1]. In particular, this exercise seeks to identify the tax burden by the nature of the direct payer, assuming constant wages and prices (excluding tax). This accounting breakdown does not therefore take into account macroeconomic feedback and does not address the distributional and intergenerational impacts [2] of taxation.

For the period from 2001 to 2014, the data is known and recorded. They are ex post and incorporate both the effects of the discretionary measures passed but also the impact of fiscal gains and shortfalls that are sensitive to the business cycle. However, for 2015 and 2016, the changes in the tax burden for households and businesses are ex ante, that is to say, they are based solely on the discretionary measures that have an impact in 2015 and 2016 and calculated in the Social, Economic and Financial Report of the 2016 Finance Bill for 2016 [Rapport économique social et financier du Projet de loi de finances pour 2016]. They therefore do not, for both years, include potential effects related to variations in tax elasticities that could modify the apparent tax burden rates. Furthermore, under the new accounting standards of the European System of Accounts (ESA) tax credits, such as the CICE, are considered here as reductions in the tax burden, and not as a public expenditure. Furthermore, the CICE tax credit is recognized at the tax burden level in terms of actual payments and not on an accrual basis.

Several major points emerge from this analysis of the recent period. First, tax rates rose sharply in the period 2010-2013, representing an increase of 3.7 percentage points of GDP, with 2.4 points borne by consumers and 1.3 by business. Over this period, fiscal austerity was relatively balanced between households and business, with the two experiencing a tax increase that was more or less proportional to their respective weights in the tax burden [3].

However, from 2014 a decoupling arose between the trends in the tax burdens for households and for business, which is continuing in 2015 and 2016. Indeed, in 2014, due to the impact of the CICE tax credit (6.4 billion euros, or 0.3 percent of GDP), the tax burden on business began to decline (by 0.2 GDP point), while the burden on households continued to rise (by 0.4 GDP point), mainly because of the hike in VAT (5.4 billion), the increase in environmental taxes (0.3 billion with the introduction of the carbon tax) and the increase in the contribution to the public electricity service (CSPE) (1.1 billion), together with the increase in social contributions for households (2.4 billion), mainly due to the rise in contribution rates to the general and complementary social security scheme and the gradual alignment of rates for civil servant with those for private-sector employees.

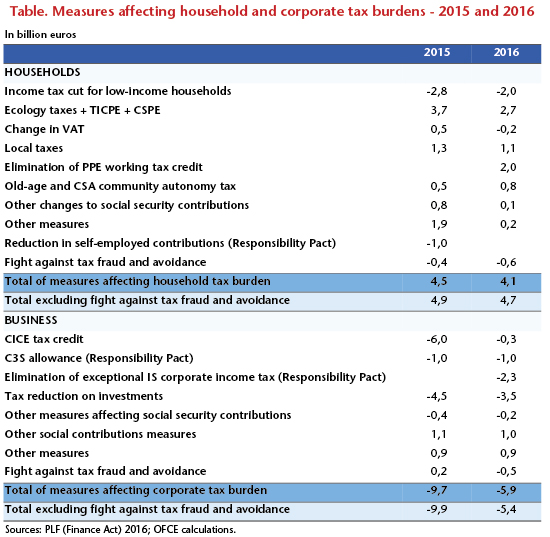

In 2015, the tax burden on business will fall by 9.7 billion euros (0.5 GDP point) with the implementation of the CICE tax credit (6 billion), the first Responsibility Pact measures (5.9 billion related to the first tranche of reductions in employer social security contributions, an allowance on the C3S tax base and a “suramortissement”, an additional tax reduction, on investment), while other measures, such as those related to pension reform, are increasing corporate taxation (1.7 billion in total). Conversely, the tax burden on households should increase in 2015 by 4.5 billion (0.2 GDP point), despite the elimination of the lowest income tax bracket (-2.8 billion) and the reduction in self-employed contributions (-1 billion). The hike in the ecological tax (carbon tax and TICPE energy tax) and the CSPE together with the non-renewal in 2015 of the exceptional income tax reductions of 2014 represent an increase in taxation on households of, respectively, 3.7 and 1.3 billion. Other measures, such as those affecting the rates of contributions to general, supplemental and civil servant pension schemes (1.2 billion), along with local taxation (1.2 billion), including the modification of the DMTO tax ceiling and measures affecting tourist and parking taxes, are also raising taxes on households.

In 2016, the tax burden on business will fall by 5.9 billion (0.3 GDP point), mainly due to the second phase of the Responsibility Pact. Reductions in employer social security contributions on wages lying between 1.6 and 3.5 times the SMIC minimum wage (3.1 billion), the elimination of the corporate income tax (IS) surcharge (2.3 billion), the second allowance on the C3S tax base (1 billion), the implementation of the CICE tax credit (0.3 billion) and the additional tax reduction on investment (0.2 billion) have been only partially offset by tax increases on business, mainly with the hike on pension contribution rates (0.6 billion). However, as in previous years, the tax burden on households will increase in 2016 by 4.1 billion (0.2 GDP point), despite a further reduction in income tax (2 billion). The main measures increasing household taxation are similar to those in 2015, including environmental taxation, with the hike in the carbon tax (1.7 billion) and the CSPE tax (1.1 billion), measures on financing pensions (0.8 billion), and the expected increase in local taxation (1.1 billion). Note that the elimination of the PPE working tax credit in 2016 will mechanically lead to an increase in the household tax burden of 2 billion[4], but this will be offset by an equivalent amount for the new Prime d’activité working tax credit.

Ultimately, over the period 2010-2016, the household tax burden will increase by 66 billion euros (3.1 GDP points) and the burden on business by 8 billion (0.4 GDP point). The household tax burden will reach a historic high in 2016, at 28.2% of GDP. Conversely, the corporate tax burden in 2016 will amount to 16.4% of GDP, less than before the 2008 crisis. And in 2017, the last phase of the Responsibility Pact (with the complete elimination of the C3S tax and the reduction of IS corporate tax rates) and the expected CICE-related reimbursements should lead to cutting corporate taxation by about 10 billion euros, bringing the corporate tax burden down to the lowest point since the early 2000s.

The need to finance measures both to enhance corporate competitiveness and to reduce the structural deficit is placing the entire burden of the fiscal adjustment on households. Thus, the reduction in income tax in 2015 and 2016 will not offset the rise in other tax measures, most of which were approved in Finance Acts prior to 2015, and seems low in relation to the tax shock that has hit households since 2010. However, how these recent tax changes affect growth and the consequent impact on inequality will depend on the way business makes use of the new resources generated by the massive decline in its tax burden since 2014. These funds could lead to a rise in wages, employment, investment or lower prices or to higher dividends and a reduction in debt. Depending on the way business allocates these, the impact to be expected on the standard of living in France and on inequality will not of course be the same. An evaluation of the impact of these changes on the tax burden will surely lead to future studies and debate.

[1] The tax burden on households includes direct taxes (CSG, CRDS, IRPP, housing tax, etc.), indirect taxes (VAT, TICPE, CSPE, excise taxes, etc.), tax on capital (ISF, DMTG, property tax, DMTO, etc.), and salaried and self-employed social security contributions. The corporate tax burden includes the various taxes on production (value-added tax and corporate property tax (ex-TP), property tax, C3S tax, etc.), taxes on wages and labour, corporate income tax and employer social security contributions.

[2] For example, employer social contributions for pensions are analyzed here as a tax burden on business and not as deferred wages for households or a transfer of income from assets to retirees.

[3] In 2013, 61% of the tax burden was on households and 39% on business. However, over the 2010-2013 period, tax increases were borne 64% by households and 36% by business, which was more or less their respective weights in taxation.

[4] The PPE credit will be replaced by the Prime d’activité working tax credit, in an equivalent amount, which also encompasses the RSA activité tax credit; for accounting purposes the PPE is considered as a public expenditure. However, this new measure should not change household income macroeconomically, but only the nature of the transfer. Thus, excluding the elimination of the PPE, the tax burden on households would increase by 2.1 billion in 2016.