By Gregory Verdugo

What is job polarization?

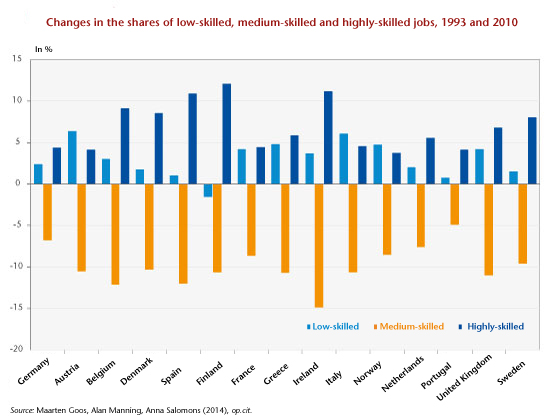

Over the past three decades, work has taken a new turn. While the post-World War II period saw a decline in wage inequalities, since the 1980s the gaps have been getting steadily wider. Differentials are increasing throughout the wage distribution, both between low and medium wages and between medium and high wages. In countries like France where wage inequalities have remained stable, the less skilled have been hit increasingly by the risk of unemployment and precarious jobs.In addition to increasing inequality, the composition of jobs has also undergone great change. To study trends in job quality, the economists Alan Manning of the London School of Economics and Maarten Goos and Anna Salomons of the University of Utrecht explored the rich data from the European Labour Force Survey for 16 European countries over the period 1993 to 2010 [1]. Based on the average wage observed in employment at the beginning of this period, they distinguish three main categories of jobs: low-skilled, medium-skilled and highly-skilled.

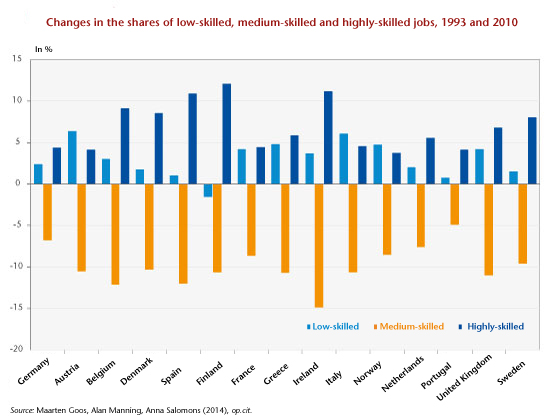

Alan Manning and his co-authors calculated how the share of these three groups in total employment is changing. Their results, presented in Figure 1, show that in most countries employment is polarizing, i.e. the share of intermediate jobs is declining sharply in favor of an increase in either low-skilled or high-skilled work. The number of medium-skilled jobs has fallen substantially: in France, these jobs decreased by 8 points between 1993 and 2010, from 47% to 39%. This compares to 12 points in Spain, 11 points in the United Kingdom, 10 points in Sweden and Denmark, 6 points in Germany and 5 points in Portugal.

While the share of intermediate occupations is shrinking, the shares of low-skilled and highly-skilled jobs are expanding. In France, these two groups have increased in a perfectly symmetrical way, by about 4% each. Thus, for every two medium-skilled jobs that disappear, one additional highly-skilled job and one unskilled job are created. Note that, compared with Belgium (+ 9%), Denmark (+ 8%) and Finland (+12%), the growth in skilled jobs has been more moderate in France, and is closer to that of Germany, Austria and Norway.

Winners and losers in the information revolution

The major upheaval going on in the labour market is due first to the nature of recent technological change, which has revolutionized the organization of businesses. Because computers operate in accordance with explicit, pre-programmed procedures and rules, they have proven very adept at performing the so-called routine tasks that characterize human labour in intermediate jobs. A computer can command an industrial robot, draw up pay slips, or distribute money. Because of their efficiency and low cost, computers have replaced the elementary and repetitive human labour that made up many intermediate jobs. The jobs most destroyed by computerization were thus those held by workers on production lines that became automated as well as those of office clerks and secretaries.

Highly-skilled workers have on the other hand been the winners from technological progress. Not only are computers unable to replace their jobs, but they also make these workers more productive. By expanding the amount of information available and facilitating its search, the Internet promotes the specialization of knowledge and makes it possible to concentrate on analytical tasks. Thanks to advances in information technology, companies are increasingly demanding more highly-skilled labour, which has made it possible to absorb the arrival of large cohorts of higher education graduates without lowering their wages.

Has international trade polarized employment?

International trade benefits the consumer by multiplying their choices and moderating prices. Indirectly, by freeing up income, it also stimulates demand and employment in the services sector. But behind the consumer is also a worker, sometimes with opposing interests. While international trade favours the former, its effect on the latter is more ambiguous.

It is now clear that medium-skilled jobs have fallen victim to the growth in trade with the developing countries. The quickening pace of trade with emerging economies with low labour costs has led companies in the developed countries to specialize in the most sophisticated design tasks that draw on information analysis and creativity. In contrast, basic production tasks have been increasingly outsourced, which has led to the destruction of a large portion of intermediate industrial jobs in the developed countries.

Recent studies on the United States [2] and France [3] have shown that, as a result of the import boom that followed after China joined the World Trade Organization in the 2000s, the labour market worsened seriously in the areas facing greatest competition from China. For France, the destruction of industrial jobs linked to Chinese competition has been quantified at 100,000 jobs from 2001 to 2007, or 20% of the 500,000 jobs lost in this sector.

How can this market be tamed?

Of course one should not forget that the labour market is a market where supply and demand is constrained by a set of norms and rules that are crucial in terms of inequality. Despite the important role of technology and trade, labour market institutions play a key role and have shaped each country’s response to computerization and the expansion of international trade and, depending on the case, have slowed or accelerated job polarization.

Many studies have noted that a minimum wage and collective wage bargaining have influenced the way inequality and employment are impacted by technological advances and globalization. These institutions have most of all had an impact on the wages of the least skilled, those they are designed to protect. For low wage earners in France, the minimum wage has dramatically closed the wage gap [4]. The centralization of wage negotiations at the branch level has also contributed to limiting wage inequalities by levelling wages between firms within a sector. Where such institutions have remained strong, they have kept low wages up and moderated wage differentials.

But if these institutions are too restrictive, they have also been suspected of undermining job creation and pushing up unemployment among low-skilled workers. They have in particular not been able to curb the destruction of jobs, and excessive protection is suspected of having discouraged job creation. In the late 1990s, Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics noted that the growth of service jobs had declined in France compared to the United States following increases in France’s minimum wage In the 1980s[5]. More recently, the researchers Julien Albertini of Humboldt University, Jean Olivier Hairault of Paris 1 University, François Langot of the University of Maine and Thepthida Sopraseuth of the University of Cergy Pontoise showed that the minimum wage has limited the growth of the non-routine manual services sector in France [6] and thus diminished the opportunities for people whose jobs were destroyed by international trade or technology. This employment deficit was particularly pronounced in activities that were intensive in low-skilled labour, such as hotels and restaurants and the retail trade[7]. A key issue facing employment policy in the years to come is how to adapt regulations to the new situation of the labour market.

The jobs of the future

Technological progress has not eliminated work. But the next wave of high-performance machines could, this time, be really different. Up to now, machines were not good at performing abstract and non-routine manual tasks, but advances in robotics and computer science could quickly change this situation. Every year has seen exponential progress in the technical possibilities for computers and robots to simulate human reasoning and intelligence: the increase in computing capabilities is making it possible to analyse and respond more skilfully to external stimuli; communication with the environment is becoming more and more sophisticated thanks to batteries of powerful sensors, aided by software that is capable, in particular, of understanding the most subtle nuances of human language and of recognizing faces and objects; data storage capabilities have been multiplying with the development of “cloud robotics”, where each robot in the network accumulates and shares experience and information with its fellow robots[8].

Some researchers believe that developments in intelligent machines and robotics are likely to replace work in a large number of jobs in the years to come. In 2015, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne, researchers at Oxford University, predicted that 47% of employees in the US hold jobs that are likely to be automated in the future[9]. They foresee a particularly heavy impact in transport and logistics, where the progress of intelligent sensors will make driverless vehicles safe and profitable.

But the jobs of the less skilled are not the only ones under threat. The growing analytical capabilities of computers now enable them to assist in decision-making in complex tasks, especially in the medical and legal fields, where they are replacing skilled labour. At the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, USA, a computer programme helps oncologists determine the most appropriate treatment for patients. The programme draws on 600,000 medical reports, 1.5 million patient records and clinical trials, and 2 million pages published in medical journals[10]. It is continuously learning and improving. In the field of law, the Clearwell System uses automatic language analysis techniques to classify the masses of documents transmitted to the parties before trial, which could amount to several thousand pages. In two days, a computer is able to make a reliable analysis of 570,000 documents. The work it saves is equal to that of dozens of lawyers, saving precious time in trial preparation[11].

Should we fear these changes? There is no fundamental economic law that guarantees that everyone will be able to find a well-paid job in the future. The less attractive work caused by polarization is a reminder that progress does not always improve job quality. But will it offer at least some jobs?

For more information: in June 2017, Gregory Verdugo published “Les nouvelles inégalités du travail: pourquoi l’emploi se polarise” [The New Labour Inequalities: Why Employment is Polarizing] at the Presses de Sciences Po, in the Collection Sécuriser l’emploi.

Link to books from Presses de Sciences Po: http://www.pressesdesciencespo.fr/fr/livre/?GCOI=27246100938740&fa=author&person_id=1987

Link to books from Cairn: https://www.cairn.info/les-nouvelles-inegalites-du-travail–9782724620900.htm

[1] Maarten Goos, Alan Manning and Anna Salomons, “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-biased Technological Change and Offshoring”, American Economic Review, 104 (8), 2014, pp. 2509-2526.

[2] David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson, “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States”, American Economic Review, 103 (6), 2013, pp. 2121-2168.

[3] Clément Malgouyres, “The Impact of Chinese Imports Competition on Employment and the Wage Distribution: Evidence from French Local Labor Markets”, EUI ECO Working Paper, 2014.

[4] Gregory Verdugo, “The Great Compression of the French Wage Structure, 1969–2008”, Labour Economics, 28, 2014, pp. 131-144.

[5] Thomas Piketty, “L’emploi dans les services en France et aux États-Unis: une analyse structurelle sur longue période”, Économie et Statistique, 318, 1998, pp. 73-99.

[6] Julien Albertini, Jean-Olivier Hairault, François Langot and Thepthida Sopraseuth, “A Tale of Two Countries: A Story of the French and US Polarization”, IZA Discussion Papers, no. 11013, June 2017.

[7] Ève Caroli and Jérôme Gautié, Bas salaires et qualité de l’emploi: l’exception française?, Paris, Editions Rue d’Ulm, 2009, p. 49

[8] Gill Pratt, “Is a Cambrian explosion coming for robotics?”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29 (3), 2015, pp. 51-60.

[9] Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne, “Technology at Work: The Future of Innovation and Employment”, Oxford Martin School, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/publications/view/1883.

[10] Jonathan Cohn, “The robot will see you now”, The Atlantic, 20 February 2013.

[11] John Markoff, “Armies of expensive lawyers replaced by cheaper software”, The New York Times, 4 March 2011.