Italy and the labour market: improvement, with caveats

By Céline Antonin

Since early 2015, the renewal of growth in Italy, the implementation of Act II of Matteo Renzi’s Jobs Act, and the reduction in business charges have undeniably contributed to the improvement on the country’s jobs front. Dynamic job creation, particularly with permanent (CDI) contracts, and an increase in the labour force, could give the impression that (partial) liberalization of Italy’s labour market has resolved the structural weaknesses it has been facing. Nevertheless, in the first half of 2016, the creation of permanent jobs has severely dried up, and what is driving growth in employment now is an increase in fixed-term (CDD) contracts. Moreover, stagnating labour productivity has accompanied more employment-yielding growth, particularly in the services sector. So in the absence of further action to address Italy’s structural weaknesses, the upturn in the labour market may not last.

A brief review of recent labour market measures

The Jobs Act is a continuation of a series of recent measures put in place since 2012 that are intended to create a more flexible labour market (see C. Antonin, Matteo Renzi’s Jobs Act: A very guarded optimism). In Act I, the Jobs Act led to extending the duration of fixed-term contracts from 12 to 36 months, eliminating waiting periods and allowing more renewal periods, while limiting the proportion of fixed-term contracts within a given company. Act II introduced a new type of permanent contract, with greater protection and severance pay increases in line with seniority. It also abolished the misuse of contratti di collaborazione, precarious work contracts often used to disguise an employment relationship. These were to be transformed into employment contracts from 1 January 2016 (1 January 2017 for the public administration).

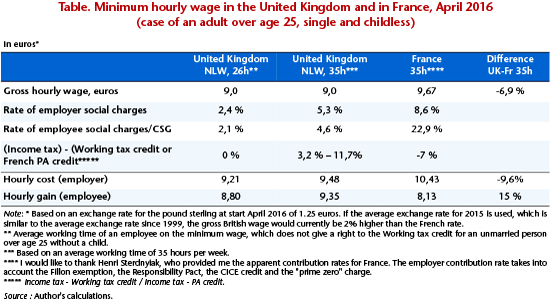

Furthermore, Italy has opted for cutting the taxation of labour: in 2015, the wage share of the IRAP (regional tax on productive activities) for employees on permanent contracts was removed. Above all, the 2015 Finance Act abolished social security contributions for 3 years on the new form of permanent contracts with greater protection, up to a limit of 8,060 euros per year for new hires between 1 January and 31 December 2015 who had not been on permanent contracts in the six months preceding their employment. The total cost to the budget was 1.8 billion euros. The programme was partially extended in 2016: companies taking on employees on the new permanent contracts in 2016 will be exempted from 40% of their social contributions for 2 years, and the cap on the exemption from contributions was reduced to 3,250 euros per employee.

A sharp increase in the number of jobs created, but stagnation in the creation of permanent jobs in 2016 …

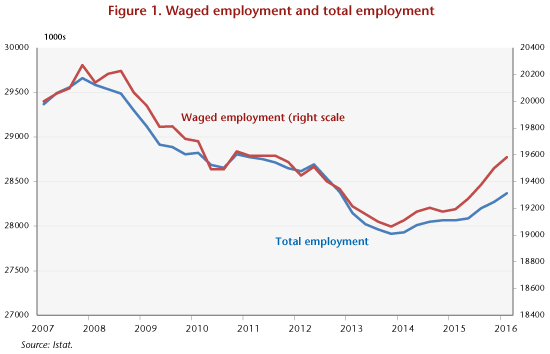

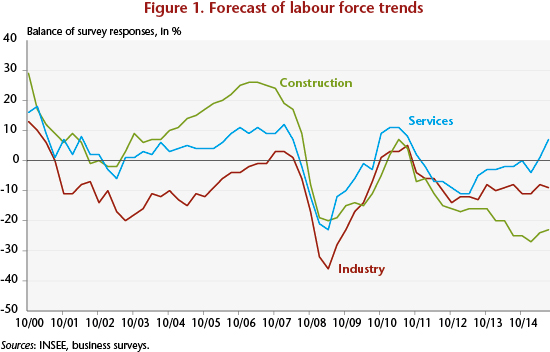

Since the beginning of 2015, the number of jobs grew strongly in Italy (Figure 1), but still falls far short of the pre-crisis level: between the first quarter of 2015 and the first quarter of 2016, the number of jobs grew by 304,000 (+391,000 permanent jobs).

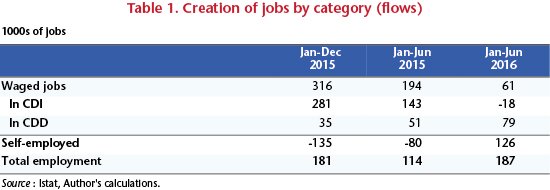

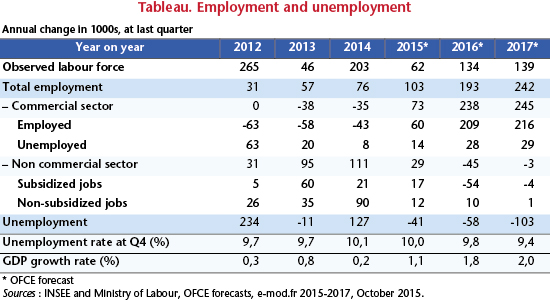

A breakdown of these figures (Table 1) reveals a major difference between 2015 and the first half of 2016: the number of new CDI jobs exploded in 2015 (+281,000 between January and December 2015), before drying up in the first half of 2016 (-18,000 from January to June 2016). In 2015, the dramatic increase in the number of CDI contracts is partly explained by the replacement of precarious jobs by permanent jobs with progressive guarantees. Thus, of the 2.0 million CDI jobs created in 2015, there were 1.4 million new CDIs and 575,000 fixed-term (CDD) contracts converted into CDIs (source: INPS). 60.8% of these new contracts benefited from the exemption from social security contributions. However, the number of new CDI contracts dropped by 33% in the first half of 2016 compared to the first half of 2015, as a result of the reduced creation of CDIs ex nihilo and a sharp fall in the conversion of CDDs into CDIs (-37%). There was nevertheless a sharp increase in the number of the self-employed in 2016, after two consecutive years of decline.

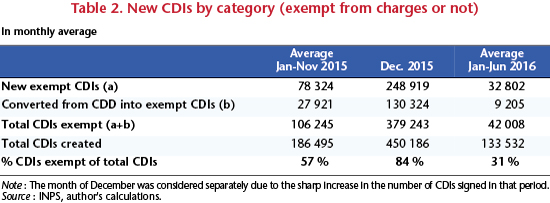

Thus, the zeal for CDIs mainly occurred in 2015, before withering in 2016. One of the reasons is the following: the reduction in social contributions for new hires on permanent contracts had a stronger impact than the Jobs Act itself. In fact, the reduction in social contributions applied only to contracts concluded in 2015. These were renewed for 2016, but on a much more limited scale (two years compared with three, with the cap on the exemption from payroll taxes cut by more than half), which may well explain the decline in enthusiasm. Moreover, an anticipation effect can be seen for the month of December 2015 (Table 2), with a steep increase in the number of CDIs fully exempt (they more than quadrupled compared to the average of the preceding eleven months). In the first half of 2016, there were on average 42,000 people hired per month who benefited from the two-year exemption on contributions, or 31% of total permanent CDI contracts[1], compared with 128,000 in 2015 (taking into account December). In 2015, the exempt contracts accounted for 61% of the total.

… but stagnation in the number of jobless due to the growth in the workforce …

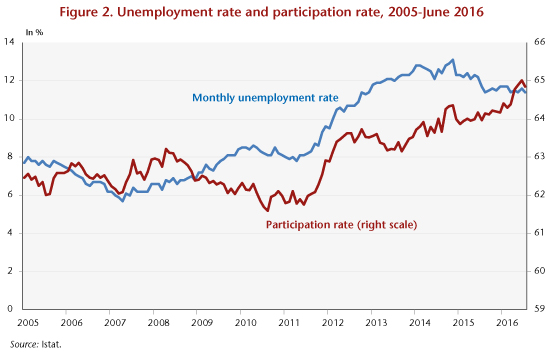

Despite the dynamic jobs market, unemployment has stagnated in Italy since mid-2015 at a level of 11.6% (Figure 2). This paradox is explained by the increase in the active population: between July 2015 and July 2016, the workforce expanded by 307,000 people. Several phenomena are behind this:

- The pension reform, which has led to seniors staying in their jobs;

- A “flexion” or bending effect: with the return of growth and the improvement in the labour market, discouraged workers have begun looking for jobs again;

- Immigration: positive net migration has had an impact on the labour market. The share of foreigners in Italy’s labour force rose from 10.7% to 11.1% between first quarter 2014 and first quarter 2016.

In conclusion, although it is not reflected in the unemployment figures, there has been an undeniable improvement in Italy’s labour market, with a great deal of job creation and marked growth in the workforce. This improvement is attributable not just to the Jobs Act, but to three combined factors: 1) the return of growth since 2015, driven by the ultra-accommodative policy of the European Central Bank, less fiscal austerity and falling oil prices; 2) the reduction in labour taxes introduced in 2015 and extended in part in 2016; and 3) the implementation of the Jobs Act. In the light of Table 2, it can also be assumed that the reduction of business social charges had a stronger impact than the Jobs Act per se.

After the upturn in 2015, the figures for the first half of 2016 call for caution. The drying up of the creation of permanent jobs in 2016 shows that the Renzi reform did not resolve the underlying problem, namely the structural weaknesses of Italy’s labour market, in particular labour productivity. To restore growth and employment, Italy really needs to address the issue of structural reform, including the poor level of innovation, research and development, the low level of competitiveness and the undercapitalization of its SMEs.

[1] including the conversion of CDD contracts into CDIs.