Rent control: will the ALUR law be sufficient?

By Sabine Le Bayon, Pierre Madec and Christine Rifflart

On 10 September 2013, Parliament began discussing the bill on “Access to housing and urban renovation [“Accès au Logement et un Urbanisme Rénové” – ALUR]. This legislation will result in stepped-up state intervention in the private rental market and complements the government decree that took effect in summer 2012 on rent control in high-pressure areas. This was an initial step in the government’s effort to curb the increase in housing costs being faced by renters. [1]

The government’s willingness to regulate the excesses of the private rental market is expected to have a rapid impact on households moving into a new home. For sitting tenants, the process is likely to take longer. In a city like Paris, we can expect that, if the highest rents decline to the ceiling set by law, average rents will fall by 4 to 6%. If through a ripple effect this then affects all rents, the deflationary impact would be greater. On the other hand, the risk of an upward drift for lower rents cannot be discarded, even if the government argues otherwise. Ultimately, the impact of the law will depend in large part on the zoning defined by the rent monitoring “observatories” that are currently being set up.

The regulatory decree: a visible, but minimal, impact

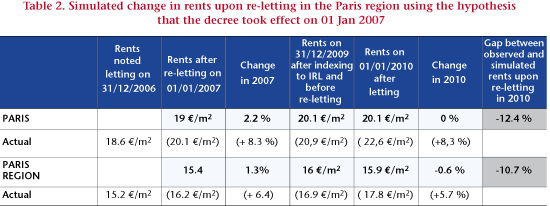

The latest annual report of the rent observatory for the Paris region [the Observatoire des loyers de l’agglomération parisienne – “OLAP”] [2] sheds some initial light on the decree’s impact on rent control. To recap, the decree holds rents upon re-letting to a maximum of the pace of the legal benchmark (the “IRL”), unless substantial work has been performed (in which case, the increase is unrestricted). Between 1 January 2012 and 1 January 2013, 51% of Paris residences offered for re-letting saw their rent increase faster than the IRL, despite the absence of substantial work. This share was lower than in 2011 (58.3%) and 2010 (59.4%), but remains close to the level observed between 2005 and 2009 (50%), prior to the existence of the decree.

The impact derived from monthly data seems a bit more conclusive. Thus, over the period from August to December 2012 when the decree was implemented, the share of rentals offered for re-letting that rose faster than the IRL cap fell by 25% on average over a year, against only 8% for the months from January to July 2012 compared to the same period in 2011.

The decree therefore does seem to have had an effect, by helping to reduce the share of rents that increased faster than the IRL cap by about 18%. However, given that if there had been full compliance with the decree no rentals would have risen more than the IRL, the impact has still been inadequate. Several factors already identified in a working document may explain this: the non-existence of benchmark rents, a lack of information about both owners and tenants, a lack of recourse, etc. One year on, it would seem that these shortcomings had a negative impact on the measure’s implementation.

A law on a larger scale

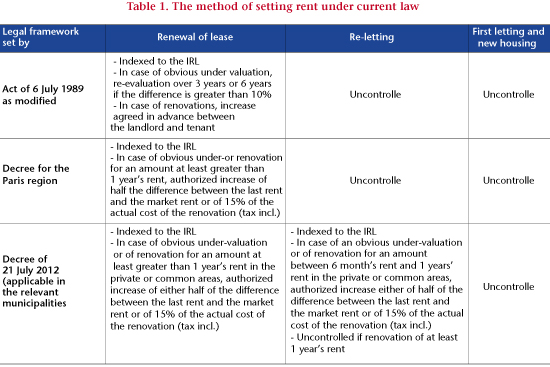

The major innovation of the ALUR law concerns the regulation of the level of rent in high-pressure areas, whereas previous decrees focused on changes in rents. Henceforth, a range of permissible rent levels will be set by law, and the decree will then regulate the maximum permitted changes [3]. To do this, every year the government sets by a prefectural decree a median benchmark rent per sq.m, per geographic area (neighbourhood, district, etc.) and per type of accommodation (one-bedroom flat, two-bedroom, etc.). So:

– For new lets or re-lettings, the rent cannot exceed the cap of 20% over the median benchmark rent, called the upwards adjusted median benchmark rent, except by documenting an exceptional additional rent (for special services, etc.). After that, any increase may not exceed the IRL, in accordance with the regulatory decree for high-pressure areas (except if there is major work);

– Upon renewal of the lease, the rent may be adjusted upwards or downwards depending on the upwards adjusted or downwards adjusted median benchmark rent [4]. Thus, a tenant (or a lessor) may bring an action to decrease (or respectively, to increase) the rent if the latter is higher (or lower) than the median rent as adjusted upwards (or downwards). In case of an increase in the rent, a mechanism for staggering this increase over time is set up. If there is a disagreement between tenant and landlord, an amicable settlement process may be initiated prior to referral to a judge within a strictly determined timeframe. Within this range, the increase is limited to the IRL;

– During a lease, the annual rent review is currently performed as now, on the basis of the IRL;

– Furnished rentals will now be covered by rent control: the prefect will set a higher benchmark rate and any change will be limited to the IRL.

The introduction of these median benchmark rents represents three major advances. On the one hand, they will be calculated from the information gathered by the rental observatories about the entire rental housing stock, and not simply from vacant housing available for rental, i.e. what is called the “market” rent. This so-called market rent is almost 10% above the average of all rents, which itself is above the median rent. This calculation method will therefore inevitably lead to lower rents (both market and average).

Similarly, choosing the median rather than the average as the benchmark rent should make for greater stability in the measure. In the event that all rents more than 20% above the median (i.e. above the upwards adjusted benchmark rent) are reduced and all other rents remain unchanged, the median remains the same. In the case of an adjustment of all rents, the median would fall, but in a lesser proportion than the average, which by definition is more sensitive to changes in extreme values.

Finally, the obligation to include in the lease both the median rent and the upwards adjusted median benchmark rent, the last rent charged and, where relevant, the amount and nature of any work performed since the last contract was signed, provides for greater transparency and a stricter regulatory framework, which should result in greater compliance with the measure.

What changes should be expected?

In 2012, out of the 390,000 residences put up for rent in Paris, 94,000 have a rent higher than the upwards adjusted median rent (3.7 euros / sq.m more on average) and 32,000 have a rent that is more than 30% below the median benchmark rent (2.4 euros / sq.m less on average). Since only rents above the upwards adjusted median rent are to be corrected, the reduction in the average rent would be 4% to 6%, depending on the area and type of housing. This reduction, although not insignificant, would at best permit a return to the rent levels recorded in 2010, before the steep inflation seen in 2011 and 2012 (+7.5% between 2010 and 2012). This adjustment in rents could nevertheless take time. Owners and tenants could easily exercise their rights at the time of a re-letting [5], but revaluations at the time of a lease renewal may take longer to realize. Despite access to information and a regulatory environment that is more favourable to the tenant, the risk of a conflict with the landlord and heightened competition in the rental market in areas where the law applies may still deter some tenants from asserting their rights.

The issue is much more complex for the 32,000 residences with rents below the downwards adjusted benchmark rent. While the quality of some of this housing can justify the difference (insalubrious, location, etc.), it is also clear that the main factor behind the weakness of some rents is the tendency of tenants to be sedentary. Thus, according to the OLAP rent observatory in Paris, the average rent for housing occupied for over 10 years by the same tenant is 20% lower than the average rent for all lets. The question thus arises of re-valuing these rents. Indeed, during a new let or a lease renewal the law allows owners to reassess up to the level of the downwards adjusted median rent – which is also in contradiction with the decree [6]. Once this level has been reached, future changes shall not exceed the IRL.

Eventually, then, some units with similar characteristics will therefore be on the market at very disparate rents, thus penalizing landlords with sedentary tenants. In contrast, tenants who have lived in their homes for a long time might well see significant revaluations in their rent (over 10%). The housing cost burden [7] on these households could thus rise, pushing those facing excessive budget constraints to migrate to areas experiencing less pressure.

Nevertheless, the possibility of revaluing the rent to the level of the market rent in case of an obvious undervaluation is already provided under existing law, i.e. the Act of 6 July 1989 (Article 17c), at the time the lease is renewed. In 2012, in Paris, 3.2% of owners made use of this article. With the new law, while readjustments should be more numerous, the inflationary impact should be weaker as the benchmark (the downwards adjusted median rent) is well below the market rent.

From this point on the issue of zoning is central: the more refined the breakdown, the more the benchmark rents will correspond to the actual characteristics of the local market. In the event of a larger division of the territory, the median benchmark rents may be too high for the less expensive neighbourhoods and too low for the more expensive ones. Meanwhile, low rents will not be re-valued much in the expensive neighbourhoods, and even less so in the others. This could lead to more “inter-neighbourhood” convergence in rents – regardless of local conditions – and less “within-neighbourhood” convergence, which would have adverse consequences for both landlord and tenant.

The impact on rents of the law currently under discussion could be all the greater given that property prices began to fall in France in 2012 and the current sluggish economy is already slowing rent hikes. But it should not be forgotten that only the construction of housing in high-pressure areas (including via densification [8]) will solve the structural problems of the market. Rent control measures are merely a temporary measure to limit the increase in the housing cost burden, but they are not by themselves sufficient.

[1] For more information, see the blog “Rent control: what is the expected impact?”

[2] The territory covered by this report is composed of Paris and what are called the “petite couronne” and the “grande couronne” (its near and far suburbs).

[3] As the rent control decree does not cover the same field as the law (38 urban areas versus 28), some areas will be subject to the control only of changes, and not of levels.

[4] While the bill is unclear on the calculation of the downwards adjusted benchmark rent, an amendment adopted in July by the Commission of the Assembly proposed that this should be at least 30% lower than the median benchmark rent. Another amendment clarifies that in case of an upward adjustment, the new rent shall not exceed the downwards adjusted median rent.

[5] In 2012, only 18% of residences on the private rental market were subject to re-letting.

[6] During the renewal of a lease or a re-letting, the rent control decree permits the owner to re-value their rent by half the gap between the last rent and the market rent.

[7] This is the share of household income spent on housing.

[8] On this subject, see the article by Xavier Timbeau, “Comment construire (au moins) un million de logements en région parisienne” [How to build (at least) one million residences in the Paris region”], Revue de l’OFCE no. 128.