The crisis and market sentiment

By Anne-Laure Delatte

Fundamental factors alone cannot explain the European crisis. A new OFCE working document shows the impact of market beliefs during this crisis. In this study, we search for where market sentiments are formed and through what channels they are transmitted. What is it that tipped market optimism over into pessimism? Our results indicate that: 1) there is a strong self-fulfilling dynamic in the European crisis: fear of default is precisely what leads to default, and 2) the small market for credit derivatives, credit default swaps (CDS), insurance instruments that were designed to protect against the risk of a borrower’s default, is the leading catalyst of market sentiment. This result should be of great concern to the politicians in charge of financial regulation, since the CDS market is opaque and concentrated, two characteristics that are conducive to abusive behaviour.

What role do investors play during a crisis? If massive sales of securities reveal the weaknesses of a certain business model, then it would be dangerous to limit them: it would be killing the messenger. But if these massive sales are triggered by a sudden turnaround in market sentiment, by investors’ panic and distrust of a State, then it is useful to understand how market beliefs are formed so as to better control them when the time comes.

To answer this question in the context of today’s European crisis, we have drawn on work on the crisis in the European Monetary System (EMS) in 1992-93, which has many common features with the current situation. At that time investors were skeptical about the credibility of the EMS and put it to the test by speculating against European currencies (sic). The pound sterling, the lira, the peseta, etc., were attacked in turn, and governments had to make concessions by devaluing their currency. At first this crisis puzzled economists, as they were unable to explain the link between the speculative attacks and fundamentals: firstly, the countries under attack did not all suffer from the same problems, and secondly, while the economic situation had deteriorated gradually, why had investors decided all of a sudden to attack one currency and not another? Finally, why did these attacks succeed? The answer was that the speculation was not determined solely by the economic situation (the “fundamentals”) but was instead self-fulfilling.

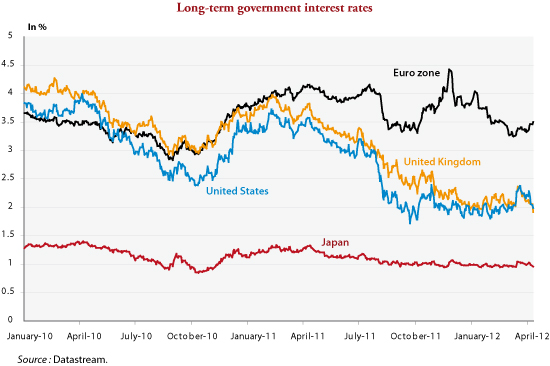

The same may well be the case today. If so, then the crisis in Spain, for example, would have its roots in the beliefs of investors: in 2011, as Spain had been designated the weakest link in the euro zone, investors sold their Spanish securities and pushed up borrowing rates. Interest payments ate into the government accounts, and the debt soared. Spain’s public deficit will be higher in 2012 than in 2011 despite its considerable austerity efforts. The crisis is self-fulfilling in that it validates investors’ beliefs a posteriori.

How could this be proved? How can we test for the presence of a self-fulfilling dynamic in the European crisis? Our proposal is as follows: market beliefs must be a critical variable if, given the same economic situation, investors nevertheless require different interest rates: when the market is optimistic, the difference in interest rates between Germany and Spain is less than when the market is pessimistic.

Our estimates confirm this hypothesis for a panel consisting of Greece, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Portugal: without any significant change in economic conditions, interest rate spreads rose suddenly following a change in the beliefs of the market.

The next question is to understand where these market beliefs are formed. We tested several hypotheses. Ultimately it is the market for credit default swaps (CDS) that plays the role of the catalyst of market sentiments. CDS are insurance products that were originally designed by banks to ensure against the possibility of a borrower’s default. An investor who holds bonds may guard against the non-reimbursement of their security at maturity by buying a CDS: the investor then pays a regular premium to the seller, who agrees to repurchase these bonds if the borrower goes bankrupt. But this insurance instrument quickly became an instrument for speculation: the vast majority of operators who buy CDS are not actually owners of an underlying bond (underlying in financial jargon). In reality, they use CDS to bet on the default of the borrower. It is as if the inhabitants of a street all insured the same house, but did not live in it, and are hoping that it catches fire.

However, our results indicate that it is precisely in this market that investors’ beliefs vis-à-vis the debt of a sovereign country are formed. In an environment marked by uncertainty and incomplete information, the CDS market transmits a signal that leads investors to believe that other investors “know something”. Given equivalent economic situations, our estimates indicate that investors require higher interest rates when CDS spreads increase.

To summarize, some European countries are subject to self-fulfilling speculative dynamics. A small insurance market is playing a destabilizing role, because investors believe in the information it provides. This is troubling for two reasons. On the one hand, as we have said, this instrument, the CDS, has become a pure instrument of speculation. On the other hand, it is a market that is unregulated, opaque and concentrated – in other words, all the ingredients for abusive behaviour … 90% of the transactions are conducted between the world’s 15 largest banks (JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank, etc.). Furthermore, these transactions are OTC, that is to say, not on an organized market, i.e. in conditions where it is difficult to monitor what’s going on.

Two avenues of reform were adopted in Europe this year: on the one hand, a prohibition against buying a CDS if you do not own the underlying bond – the law will enter into force in November 2012 throughout the European Union. Second is a requirement to go through an organized market in order to ensure the transparency of transactions. Unfortunately, neither of these reforms is satisfactory. Why? The answer in the next post…