Why a negative interest rate?

Christophe Blot and Fabien Labondance

As expected, on 5 June 2014 the European Central Bank (ECB) unleashed an arsenal of new unconventional measures. The aim is to curb deflationary tendencies in the euro zone. Among the measures announced, the ECB decided in particular to apply a negative interest rate to deposit facilities. This unprecedented step deserves an explanation.

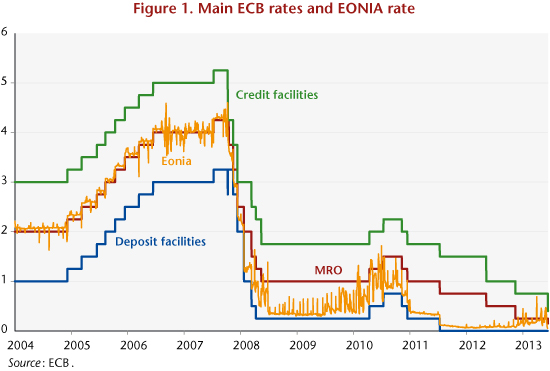

Note that since July 2012, the rate on deposit facilities has been 0%. It now falls to -0.10%, meaning that a bank depositing cash at the ECB will have its deposit reduced by that rate. Before considering the repercussions of this measure, it is worth clarifying the role of deposit facilities. The ECB’s activity is baed on loans to credit institutions in the euro zone through the channel of main refinancing operations (MRO) or long-term refinancing operations (LTRO). Prior to the crisis, these operations were conducted at variable rates based on an auction mechanism, but since October 2008 they have been conducted at fixed rates. The refinancing operation rates must allow the ECB to influence the rate charged by credit institutions for interbank loans (Euro OverNight Index Average rates, or Eonia) and, through this channel, the entire range of bank rates and market rates. To ensure the Eonia is not too volatile, the ECB provides the banks with two facilities: credit facilities, enabling them to borrow from the ECB for a period of 24 hours, and deposit facilities, enabling them to make cash deposits with the ECB for a period of 24 hours. In case of a liquidity crisis, the banks thus have a guarantee of being able to lend or borrow via the ECB, at a higher for credit facilities or a lower rate for deposit facilities. These rates can then be used to regulate fluctuations in the Eonia, as shown in Figure 1.

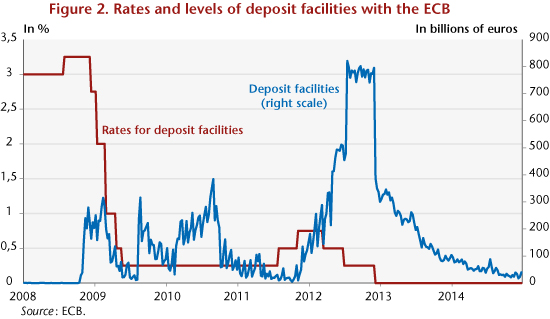

In practice, until the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, banks made little use of deposit facilities, indicating that the interbank market was functioning normally. The situation has radically changed since then, and the amount of deposits left with the ECB has fluctuated to a greater or lesser extent, depending on concerns over the sovereign bond crisis (Figure 2). The height of the crisis in spring 2012 coincided with a peak in the amounts deposited by the banks, which had excess liquidity. Over a period of three months, around 800 billion euros (equivalent to just under 10% of euro zone GDP), paid at 0.25%, were deposited by Europe’s banks. In the context of fear of a euro zone collapse and uncertainty about the financial situation of financial and non-financial agents, the banks have been depositing poorly compensated sums with the ECB. They chose to do this rather than to exchange the excess liquidity in the money market or support activity by lending to companies or buying shares. It was not until Mario Draghi’s statement in July 2012 that the ECB would do “whatever it takes” to support the euro zone that confidence returned and these sums fell. It was also then that the rate went down to 0%, further reducing the incentive to use the deposit facilities. The level of deposits fell by half, from 795.2 billion euros to 386.8 billion. Since then, they have declined gradually, but are still high, especially given that they receive no interest. In the last week of May 2014, there were still 40 billion euros in deposits (Figure 2).

This situation prompted the ECB to set a negative rate in order to encourage commercial banks to reallocate this money. We can be sure that once the negative rate applies, the level of deposits will quickly drop to zero. Even so, this will mean an impulse of only 40 billion euros, and further action will be needed to support the real economy. On its own, this step by the ECB has certainly not convinced the markets that it has dealt with the situation.

The ECB has thus once again demonstrated its proactive approach to curbing the risks facing the euro area. Its reaction can be compared to the response of Europe’s other institutions, which have struggled to fully take on board the depth of the crisis. Looking outside the euro zone, it is noteworthy that the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England moved with greater speed, even though the risk of deflation was lower in the United States and the United Kingdom. This active approach is perhaps no stranger to the renewed growth seen in these countries. The ECB’s action is therefore welcome. Now we need to hope that it will stave off the risk of deflation hanging over the euro zone, a risk that could have been avoided if the euro zone’s governments had not generally adopted austerity policies, and if the ECB had taken less of a wait-and-see attitude.