By Catherine Mathieu and Henri Sterdyniak

The British vote to leave the European Union is aggravating the political crisis in Europe and in many European countries. Leaving the EU has become a possible alternative for the peoples of Europe, which may encourage parties advocating national sovereignty. The United Kingdom’s departure automatically increases the weight of the Franco-German couple, which could destabilize Europe. If Scotland leaves the UK to join the EU, independence movements in other regions (Catalonia, Corsica, etc.) could seek a similar outcome. But the fragility of Europe also stems from the failure of the strategy of “fiscal discipline / structural reforms”.

The departure of the United Kingdom, a fierce advocate of economic liberalism and opponent of any increase in the European budget and in the powers of Europe’s institutions, as well as of a social Europe, could change the dynamics of the debate in Europe, but some East European countries, the Netherlands and Germany have always had the same position as the UK. The departure will not, by itself, cause a shift in European policy. On the other hand, the liberalization of services and the financial sector, which the UK has been pushing for, could be slowed. The British Commissioner, Jonathan Hill, head of financial services and capital markets, should be promptly replaced. This will raise the sensitive issue of British EU officials, who in any case can no longer occupy positions of responsibility.

This will also open up a period of economic and financial uncertainty. The reaction of the financial markets, which do not like uncertainty and are in any case volatile, should not be accorded an excessive importance. The pound sterling has of course rapidly depreciated by 10% against the euro, but it was probably overvalued, as evidenced by the British current account deficit of around 6.5% of GDP in 2015.

According to Article 50 of the European Constitution, any country that decides to leave the EU should negotiate a withdrawal agreement, which sets the exit date[1]. Otherwise, after two years the country is automatically outside the Union. The negotiations will be delicate, and must of necessity deal with all the issues. During this period, the UK will remain in the EU. European countries will have to choose between two attitudes. An understanding attitude would be to sign a free trade agreement quickly, with the goal of maintaining trade and financial relations with the UK as a privileged partner of Europe. This would minimize the economic consequences of Brexit for both the EU and the UK. However, it seems difficult to see how the UK could simultaneously enjoy both complete freedom for its own economic organization and full access to Europe’s markets. The UK should not enjoy more favourable conditions than those of the current members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA – Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein) and Switzerland; like them, it should undoubtedly integrate the single market legislation (in particular the free movement of persons) and contribute to the EU budget. The issue of standards, such as the European passport for financial institutions (this is now granted to the EFTA countries, but not to Switzerland), etc., would be posed very quickly. The UK may have to choose whether to comply with European standards on which it will not have a say or to be subject to regulatory barriers. The negotiations will of course be open-ended. The UK could argue for a Europe that is more open to countries outside the EU. But how much weight will it have once it’s out?

A tough attitude intended to punish London so as to set an example and deter future candidates from leaving would instead require the UK to renegotiate all trade treaties from scratch (i.e. from WTO rules) so as to encourage multinational companies to relocate their factories and headquarters to mainland Europe and close British banks’ access to the European market in order to push them to repatriate euro zone banking and financial activity to Paris or Frankfurt. But it would be difficult for Europe, a supporter of the free movement of goods, services, people and business, to start erecting barriers against the UK. The euro zone has a current account surplus of 130 billion euros with the UK: does it want to call this into question? European companies that export to the UK would oppose this. Industrial cooperation agreements (Airbus, arms, energy, etc.) could only be challenged with difficulty. A priori it would seem unlikely that London would erect tariff barriers against European products, unless in retaliation. Conversely, London could play the card of setting up tax and regulatory havens, particularly in financial matters. It could not, however, avoid international constraints (agreements such as at COP21, on the fight against tax avoidance, on the international exchange of tax and banking information, etc.). The risk would be to start a costly game of mutual reprisals (one that it would be difficult for Europe, divided between countries with different interests, to lead).

Upon leaving the European Union, the United Kingdom, a net contributor to the EU, would a priori save about 9 billion euros per year, or 0.35% of its GDP. However, the EFTA countries and Switzerland contribute to the EU budget as part of the single market. Again, everything depends on the negotiations. It would seem that the savings for the UK will be only about 4.5 billion euros, which the other Member countries will have to make up (at a cost of around 0.5 billion euros for France).

Given the uncertainty of the negotiations (and of exchange rate trends), all assessments of Brexit’s impact on other EU countries can only be very tentative. Moreover, this will necessarily have only a second-order impact on the EU countries: if tariff or non-tariff barriers reduce French exports of cars to the UK and of British cars to France, French manufacturers can supply their national markets while facing less competition and can also turn to third countries. It is nevertheless useful to have an order of magnitude: in 2015, exports from France (from the EU) to the UK represented 1.45% of GDP (respectively 2.2%); exports from the UK to the EU represented 7.1% of British GDP. A priori, an equivalent impact on UK / EU trade will have 3.2 times less impact on the EU than on the UK.

According to the OECD[2], the fall in EU GDP will come to 0.8% by 2023 (against 2.5% for the UK), whereas remaining in the EU, participating in the deepening of the single market and signing free trade agreements with the rest of the world would lead to a rise in GDP for all EU countries. But how credible is this last assertion, given the euro zone’s current poor performance and the cost for the economic and social cohesion of European countries of opening the borders? But if Europe is functioning poorly, then leaving should improve market prospects. The UK’s foreign trade would suffer a contraction, which would hurt its long-term productivity, but despite its openness the British economy’s productivity is already weak. The OECD does not raise the question of principle: should a country give up its political sovereignty to benefit from the potential positive effects of trade liberalization?

According to the Bertelsmann Foundation[3], the reduction in EU GDP (excluding the UK) in 2030 would range from 0.10% in the case of a soft exit (the UK having a status similar to that of Norway) to 0.36% in the worst case (the UK having to renegotiate all its trade treaties); France would be little affected (-0.06% to -0.27%), but Ireland, Belgium and Luxembourg more so. The study multiplied these figures by five to incorporate medium-term dynamics, with the reduction in foreign trade expected to have adverse effects on productivity.

Euler-Hermes also reported very weak figures for the EU countries: a fall of 0.4% in GDP with a free trade agreement and of 0.6% without an agreement. The impact would be greater for the Netherlands, Ireland and Belgium.

Europe needs to rebound, with or without the United Kingdom…

Europe must learn the lessons from the British crisis, which follows on the debt crisis of the southern European countries, the Greek crisis, and austerity, as well as from the migrant crisis. It will not be easy. There is a need to rethink both the content of EU policies and their institutional framework. Is the EU up to the challenge?

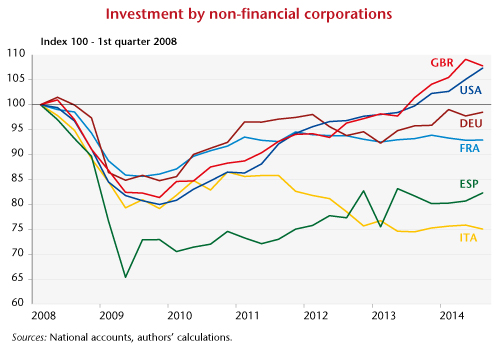

The imbalances between EU Member countries grew from 1999 to 2007. Since 2010, the euro zone has not been able to develop a coordinated strategy enabling it to restore a satisfactory level of employment and reduce the imbalances between Member states. The economic performance of many euro zone countries has been poor, and downright catastrophic in southern Europe. The strategy implemented in the euro zone since 1999, and strengthened since 2010 – “fiscal discipline / structural reforms” – has hardly produced satisfactory results socially or economically. On the contrary, it gives people the feeling of being dispossessed of any democratic power. This is especially true for countries that benefited from assistance from the Troika (Greece, Portugal, Ireland) or the European Central Bank (Italy, Spain). The Juncker plan that was intended to boost investment in Europe marked a turning point in 2015, but it remains timid and poorly taken up: it was not accompanied by a review of macroeconomic and structural policy. There are important disagreements in Europe both between nations and between political and social forces. In the current situation, Europe needs a strong economic strategy, but it has not been possible to agree on one collectively in today’s Europe.

There are two fundamental reasons for this morass. The first concerns all the developed countries. Globalization is creating a deeper and deeper divide between those who benefit from it and those who lose[4]. Inequalities in income and status are widening. Stable, well-paid jobs are disappearing. The working classes are the direct victims of competition from low-wage countries (Asian countries and former Soviet bloc countries). They are being asked to accept cuts in wages, social benefits, and employment rights. In this situation, the elite and the ruling classes can be open-spirited, globalist and pro-European, while the people are protectionist and nationalist. This same phenomenon underlies the rise of France’s National Front, Germany’s AFD, UKIP, and in the US the Republican Donald Trump.

Europe is currently operated according to a liberal, technocratic federalism, which seeks to impose on people policies and reforms that they are refusing, sometimes for reasons that are legitimate, sometimes questionable, and sometimes contradictory. The fact is that Europe in its current state is undermining solidarity and national cohesion and preventing countries from choosing a specific strategy. The return to national sovereignty is a general temptation.

Furthermore, Europe is not a country. There are significant differences in interests, situations, institutions and ideologies between peoples, which render progress difficult. Because of the differences in national situations, many arrangements (the single monetary policy, the free movement of capital and people) pose problems. Rules that had no real economic foundation were introduced in the Stability Pact and the Budgetary Treaty: these did not come into question after the financial crisis. In many countries, the ruling classes, political leaders and senior civil servants have chosen to minimize these problems, so as not to upset European construction. Crucial issues concerning the harmonization of taxes, social welfare, wages and regulations have been deliberately forgotten. How can convergence towards a social Europe and a fiscal Europe be achieved between countries whose peoples are attached to structurally different systems? Given the difficulties of monetary Europe, who would wish for a budgetary Europe, which would take Europe further from democracy?

In the UK-EU Agreement of 19 February, the UK has recalled the principles of subsidiarity. It is understandable that countries concerned about national sovereignty are annoyed (if not more) by the EU’s relentless intrusions into areas that fall under national jurisdiction, where European intervention does not bring added value. It is also understandable that these countries refuse to constantly justify their economic policies and their economic, social or legal rules to Brussels when these have no impact on the other Member states. The UK noted that the issues of justice, security and individual liberties are still subject to national competence. Europe needs to take this feeling of exasperation into account. After the British departure, it needs to decide between two strategies: to strengthen Europe at the risk of further fuelling people’s sense of being powerless, or to scale down the ambition of European construction.

The departure of the United Kingdom, the de facto distancing of some Central European countries (Poland, Hungary) and the reticence of Denmark and Sweden could lead to an explicit switch to a two-tiered EU. Many national or European intellectuals and politicians think that this crisis could provide just such an opportunity. Europe would be explicitly divided into three groupings. The first would bring together the countries of the euro zone, which would all agree to new transfers of sovereignty and to build a stronger budgetary, fiscal, social and political union. A second grouping would bring together the European countries that do not wish to participate in such a union. The last grouping would include countries linked to Europe through a free trade agreement (currently Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Switzerland, and later the UK and other countries).

Such a project would, however, pose many problems. Europe’s institutions would have to be split between euro zone institutions operating on a federal basis (which need to be made more democratic) and EU institutions continuing to operate in the Union manner of the Member states. Many countries currently outside the euro zone are opposed to this kind of change, which they feel would marginalize them as “second-class” members. The functioning of Europe would become even more complicated if there were both a European Parliament and a euro zone Parliament, euro zone commissioners, euro zone and EU financial transfers, and so on. This is already the case for instance with the European Banking Agency and the European Central Bank. Many questions would have to be decided two or three times (once in the euro zone, again at the EU level, and again for the free trade area).

Depending on the issue, the Member country could choose its grouping, and things would quickly head towards an à la carte union. This is hardly compatible with the democratization of Europe, as soon there would be a Parliament for every question.

The members of the third grouping would then be in an even more difficult situation, with the obligation to comply with regulations over which they had no power. Should our partner countries be placed in the dilemma of either accepting heavy losses of sovereignty (in political and social matters) or being denied the benefits of free trade?

There is clearly no agreement between the peoples of Europe, even within the euro zone, on moving towards a federal Europe, with all the convergences that this would imply. In the recent period, the five Council Presidents and the Commission proposed new steps towards European federalism: creating a European Budget Committee, establishing independent Competitiveness Councils, conditioning the granting of Structural Funds on respect for budgetary discipline and the implementation of structural reforms, establishing a European Treasury and a euro zone minister of finance, moving towards a financial union, and partially unifying the unemployment insurance systems. These developments would reinforce the technocratic bodies to the detriment of democratically elected governments. It would be unpleasant if these were implemented, as is already partially the case, without the people being consulted.

Furthermore, no one knows how to proceed with convergence on tax and social matters. Upwards or downwards? Some proposals call for a political union in which decisions are taken democratically by a euro zone government and parliament. But can anyone imagine a federal authority, even a democratic one, that is able to take into account national specificities in a Europe composed of heterogeneous countries? What about decisions concerning the French pension system taken by a European Parliament? Or a finance minister for the zone imposing spending cuts on Member countries (as the Troika did in Greece)? Or automatic standards on public deficits? In our opinion, given the current disparity in Europe, economic policies must be coordinated between countries, not decided by a central authority.

Europe needs to reflect on its future. Using the current crisis to move forward towards an “ever closer union” without more thought would be dangerous. Europe must live with a contradiction: the national sovereignties that peoples are attached to have to be respected as much as possible, while Europe must implement a strong and consistent macroeconomic and social strategy. Europe has no meaning in itself, but only in so far as it implements the project of defending a specific model of society, developing it to integrate the ecological transition, eradicating mass unemployment, and solving the imbalances within Europe in a concerted and united manner. But there is no agreement within Europe on the strategy needed to achieve these goals. Europe, which has been unable to generally lead the Member countries out of recession or to implement a coherent strategy to deal with globalization, has become unpopular. Only after a successful change of policies will it regain the support of the peoples and be able to make institutional progress.

[1] See in particular the report of the French Senate by Albéric de Montgolfier: Les conséquences économiques et budgétaires d’une éventuelle sortie du Royaume-Uni de l’Union Européenne [The economic and budgetary consequences of a future withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union], June 2016.

[2] OECD, 2016, The Economic Consequences of Brexit: A Taxing Decision, April. Note that to treat leaving the euro as a tax increase does not make economic sense and represents a communication that is unworthy of the OECD.

[3] Brexit – potential economic consequences if the UK exits the EU, Policy Brief, 2015/05.

[4] See, for example, Joseph E. Stiglitz, 2014, “Le prix de l’inégalité”, Les Liens qui libèrent, Paris.