Is the ECB impotent?

Christophe Blot, Jérôme Creel, Paul Hubert and Fabien Labondance

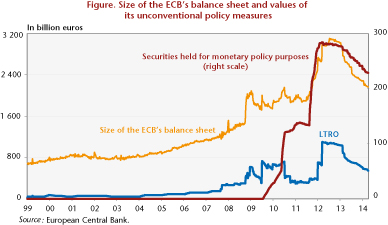

In June 2014, the ECB announced a set of new measures (a detailed description of which is provided in a special study entitled, “How can the fragmentation of the euro zone banking system be fought?”, Revue de l’OFCE, No. 136, in French) in order to halt the lowering of inflation and sustain growth. Mario Draghi then clarified the objectives of the ECB’s monetary policy by indicating that the Bank wanted to expand its balance sheet by a trillion euros to return to a level close to that seen in the summer of 2012. Among the measures taken, much was expected from the new targeted long-term refinancing operation (TLTRO), which gives banks in the euro zone access to ECB refinancing with a maturity of 4 years in return for providing credit to the private sector (excluding mortgages). However, after the first two allocations (24 September 2014 and 11 December 2014), the picture has become rather complicated, with the amounts allocated well below expectations. This reflects the difficulty the ECB is having in fighting effectively against the risk of deflation.

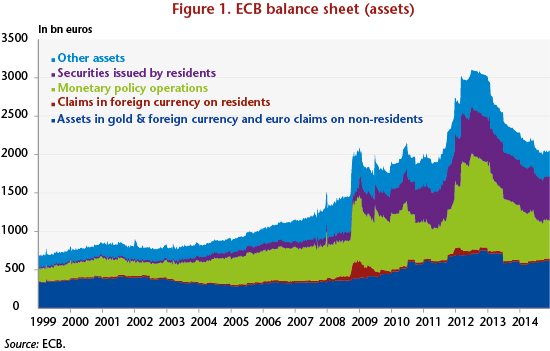

Indeed, having allotted 82.6 billion euros in September (versus anticipations of between 130 and 150 billion), the ECB granted “only” 130 billion on December 11, i.e. once again a lower amount than had been anticipated. So we are a long way from the maximum amount of 400 billion euros that had been evoked by Mario Draghi in June 2014 for these two operations. Moreover, these first two allotments were clearly insufficient to boost the ECB’s balance sheet significantly (Figure 1), and all the more so as banks are continuing to reimburse the three-year loans that they received in late 2011 and early 2012 in the very long-term refinancing operation (VLTRO) [1]. What explains the banks’ reluctance to make use of this operation, even though it allows them to refinance the loans granted at a very low rate for a 4 year term?

The first is that the banks already have very broad and very advantageous access to ECB liquidity through the monetary policy operations already implemented by the ECB[2]. These operations actually offer a lower interest rate than does the TLTRO (0.05% against 0.15%). Similarly, a TLTRO is not more attractive than some long-term market financing, especially since many banks do not have financing constraints. TLTRO is thus of marginal interest, due to the maturity of the operation, and more restrictive because it is conditioned on the distribution of credit. For the first two operations conducted in September and December 2014, the allotment could not exceed 7% of outstanding loans to the non-financial private sector in the euro zone, excluding loans for housing, as of 30 April 2014. A new series of TLTRO will be conducted between March 2015 and June 2016, on a quarterly basis. This time the maximum amount that can be allocated to the banks will depend on the growth in outstanding loans to the non-financial private sector in the euro zone, excluding loans for housing, between 30 April 2014 and the date of the operation in question.

The second explanation is that the weakness of credit in the euro zone is not simply the result of supply factors but also demand factors. Sluggish activity and private agents’ efforts to shed debt are holding back lending.

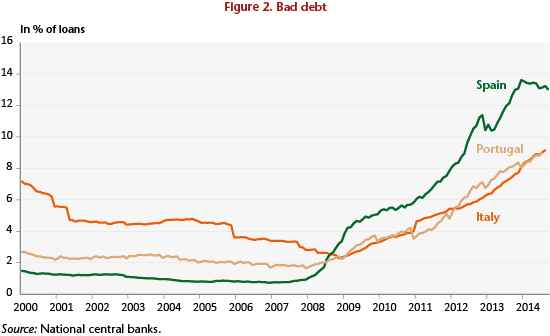

Third, beyond banks’ ability to find refinancing, it is also possible that they are trying to reduce their exposure to risk. The problem is thus related to their assets. However, non-performing loans are still at a very high level, especially in Spain and Italy (Figure 2). In addition, although the Asset Quality Review (AQR) conducted by the ECB has revealed that insolvency risks are limited in the euro zone, the report also points out that some banks are highly leveraged and that they have mainly used the available liquidity to buy government bonds in order to meet their capital requirements. They are then reducing their balance sheet risk by limiting loans to the private sector.

Finally, two uncertainties are also reducing the banks’ participation in the TLTRO. The first concerns the stigma attached to the conditionality of the TLTRO and to the fact that banks that do not meet their commitments on the distribution of credit will be required to repay the financing obtained from the ECB after two years. So banks facing uncertainty about their ability to increase their lending may very well wish to avoid the prospect of having to repay the funds sooner. The second factor concerns uncertainties about the programs for purchasing ABS and covered bonds[3]. The banks could also turn to these programs to get cash in exchange for the sale of assets that they would like to get rid of.

Has monetary policy become totally ineffective? The answer is certainly no, since by giving banks a guarantee that they can refinance their activity through various programs (TLTRO, ABS, covered bonds, etc.), the ECB is reducing the risk that credit will be rationed due to the deteriorated state of some banks’ liabilities. Monetary policy is thus helping to free up the credit channel. But its effects are nevertheless limited, as is suggested by Bech, Gambacorta and Kharroubi (2012) , who show that monetary policy is less effective in periods of recovery following a financial crisis. Can we get out of this impasse? This observation on the effectiveness of monetary policy shows that the ECB should not be viewed as the be-all and end-all. It is still essential to complement its support for activity through an expansionary fiscal policy across the euro zone. This point was also reiterated by the President of the ECB during this summer’s conference at Jackson Hole: “Demand side policies are not only justified by the significant cyclical component in unemployment. They are also relevant because, given prevailing uncertainty, they help insure against the risk that a weak economy is contributing to hysteresis effects.”

[1] See the special study in the Revue de l’OFCE no. 136, “Comment lutter contre la fragmentation du système bancaire de la zone euro?” for an examination of the various monetary policy measures taken by the ECB since the onset of the financial crisis and an estimate of their impact on the real economy.

[2] This includes standard monetary policy operations as well as the VLTRO operation through which the ECB provided liquidity for an exceptional term of 3 years in December 2011 and February 2012.

[3] This involves programs for the purchase of securities in the market and not cash distributed directly to the banks. The covered bonds and ABS are securities pledged on assets whose remuneration depends on that of the underlying asset, which is by necessity a mortgage in the case of covered bonds and which in the case of ABS may include other types of loans (credit cards, cash loans to businesses, etc.).