The erosion of France’s productive base: causes and remedies

Xavier Ragot, President of the OFCE and the CNRS

The deindustrialization of France, and more generally the difficulties facing sectors exposed to international competition, reflects trends that have been at work in France and in Europe for more than a decade. Indeed, while the strictly financial moment when the crisis struck in 2007 was the result of the bursting of the American real estate bubble, the scale of its impact on Europe’s economy cannot be understood without looking at vulnerabilities that have previously been neglected.

In “Érosion du tissu productif en France: Causes et remèdes”, OFCE working document no. 2015-04, Michel Aglietta and I offer a summary of both the microeconomic and macroeconomic factors behind this productive drift. Such a synthesis is essential. Before proposing any policy changes for France, it is necessary to make a coherent diagnosis of major trends in international trade as well as of the real situation of France’s productive fabric.

European divergences

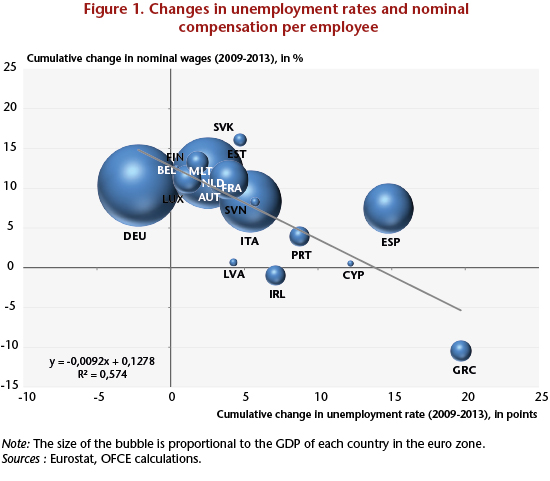

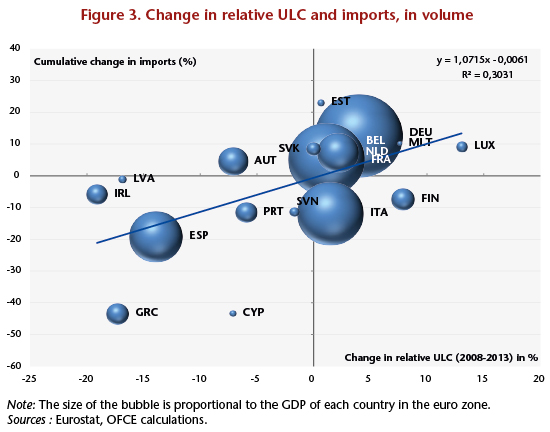

The starting point is the surprising divergence seen in Europe. The euro zone’s two largest countries, Germany and France, have diverged in an unprecedented way since the mid-1990s. While property prices remained stable in Germany, in France they increased by a factor of 2.5, hitting the country with two negative consequences: a high cost of living for its employees, and a collapse in property investment by its businesses. Wages in Germany are now 20% lower than in France due to the wage moderation implemented to manage the former’s reunification process. Furthermore, until the crisis, real short-term interest rates (which take into account inflation differentials) were about 1 percentage point lower in France and Spain than in Germany. This change in the price of the production factors (higher real interest rates and lower wages in Germany than in France) did not give rise to a greater substitution of capital for labour in France. There was little difference between the two countries in the investment rate, which was relatively stable in both. Other indicators, such as the number of robots, indicate on the contrary that there was less modernization of France’s productive fabric. These changes in factor prices have not therefore translated into an adjustment in the productive fabric, but have instead led to an unsustainable divergence in the current accounts.

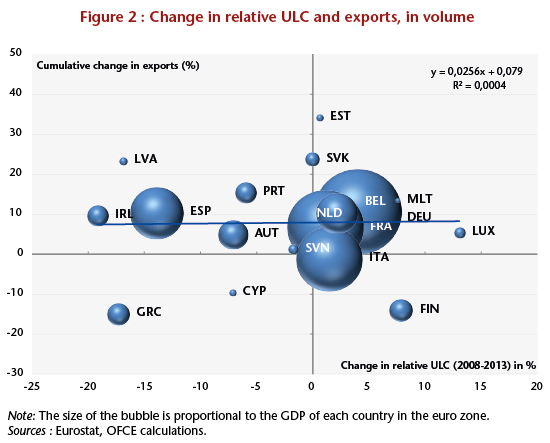

Current account balances are crucial concepts for measuring disequilibria within Europe. A positive current account means that a country is lending to the rest of the world, while a negative current account means that it is borrowing from the rest of the world. While European rules have focused attention on the public deficit alone, the proper measure of a country’s indebtedness is the current account, the sum of public and private debt. On this measure, Germany’s current account is one of the most positive in the world, meaning that it is lending heavily to other countries. While over the last three years the differences between European current accounts have been narrowing, this is the result more of a contraction in activity due to austerity measures than of a modernization of the productive base in countries with negative current accounts. The European framework for analysing macroeconomic imbalances does of course have numerous indicators, including the current account. However, in practice the multiplicity of indicators gives a crucial role to the numerical public deficit targets. So while the framework for European surveillance seems very general in its assessment of economic imbalances, it is the short-term budgetary aspect alone that dominates analysis. Don’t forget that Spain’s public debt was less than 40% of GDP in 2007, but over 90% of GDP in 2013. Low public debts are not therefore a sufficient condition for macroeconomic stability, just as public debts that are temporarily high are not necessarily a sign of structural problems.

The fragility of France’s productive base

In this sense, corporate data can be used to gain insight into trends in the French economy. French companies did of course experience a fall in margins, but this has mainly affected sectors exposed to international competition. Corporate profitability (which finances the payment of dividends and interest and contributes to investment) fell from 6.2% in 2000 to less than 5% in 2012. Despite this decline, the investment rate held steady in all business categories during the period, in part funded by corporate savings, which declined from a rate of 16% in 2000 to 13% in 2012. The result has been a substantial rise in corporate debt, although up to now this has not led by higher debt costs due to the fall in interest rates. All these factors are inevitably fuelling concern about the health of our productive fabric: France’s businesses have responded to economic difficulties, not by innovation, but by financializing their balance sheets and taking on debt.

Towards partnership in governance

To innovate, invest and upscale, France’s companies must make efforts over the long term – this is the only way there will be a process of reconvergence in Europe. The point is not to maximize short-term financial returns, through for example excessive dividend payments, but rather to invest over horizons that are typically considered (too) long by companies. As a result, making improvements to France’s productive fabric will require shifting corporate governance towards a model based on stronger partnerships and a more long-term vision in order to invest in employees’ skills and qualifications, in intangible assets, and in new technologies. Social dialogue is not just about income distribution and tax reform but is also essential within companies in order to ensure the mobilization of our only productive wealth, men and women who are putting their all into their work.