Pigeons: how to tax capital gains (1/2)

By Guillaume Allègre and Xavier Timbeau

After having proposed in the 2013 Budget Bill to tax gains from the sale of securities at the progressive scale used by France’s income tax, and no longer at a proportional rate of 19%, the government has now promised to correct its work under the pressure of a group of entrepreneurs who rallied on the social networks under the hashtag #geonpi (“pigeons”, using French verlan slang, which inverts syllables). An amendment to the Bill was passed to this effect. Here we discuss the equitable taxation of capital gains on securities. In a second post, we will discuss the specificity of entrepreneurship.

The Budget Bill reflects François Hollande’s commitment to enact a major tax reform to make the contribution of each fairer: “capital income will be taxed just like work income” (Commitment 14 of the 60 commitments for France). When the capital results from the saving of employment income that was paid at a “normal” rate, taxing it poses the problem of double taxation and may seem questionable. Note, however, that in a financialized economy income from capital is not simply the result of saving, but also the direct result of an activity (see issue 122 of the special revue de l’OFCE issue on tax reform, and in particular Allègre, Plane and Timbeau on “Réformer la fiscalité du patrimoine? “Reforming wealth taxation”). In this sense, capital income derives from households’ ability to pay, just as does labour income. The progressive tax on income must apply to all income, whether it comes from capital or labour, in order to respect the principle of horizontal equity, i.e. “on equal income, equal tax”.

With respect to gains on disposal, only the change in the real value of the capital can be considered as income: if the value of a good has increased at the same rate as inflation, the nominal gain, even if positive, does not cover the implicit cost of ownership. The Bill provided that gains on disposals are entitled to an allowance based on the length of holding, which was copied from that applicable to real estate gains. The amendment reduces the durations of holding relative to the original text:

– the capital gains taxable at the income tax rate are reduced by an allowance equal to:

a) 20% of their value when the shares, units, rights or securities have been held for at least two years and less than four years at the date of sale;

b) 30% of their value when the stocks, units, rights or securities have been held for at least four years and less than six years at the date of sale;

c) 40% of their value when the stocks, units, rights or securities have been held for at least six years.

This type of allowance on the nominal capital gain is a poor instrument for taking account of inflation: if the variation of the real value of the capital is zero, then the tax should be zero (there is no real income), whereas an allowance will only reduce it; and on the contrary, if the change in the real value of the capital is much higher than inflation, then the allowance will be too favourable; the allowance is a fixed amount based on increments, while price rises are a continuous phenomenon. At least the allowance does not reach 100%, which is still the case for most real estate capital gains, which are totally exempt from gains on property that has been held 30 years. A good system would not apply an allowance to the nominal gain, but would actualize the purchase price using an index that reflects prices, which would make it possible to determine changes in the real value of the asset.

Examples: a good is purchased in January 2000 for 100. It is re-sold for 200 in January 2011. The nominal gain is 100. The allowance of 40% applies, and hence, in the system proposed by the government, the taxation would be on 60, and incorporated in the income tax. The variation in the real value of the capital is 79, which is the most reasonable basis for the taxation (we are not interested here in the rate of taxation, but the taxable base).

If, however, in January 2011 the property were re-sold for 120, the amount used by the allowance system would be 8, whereas the variation in the real value of the capital would be -1.

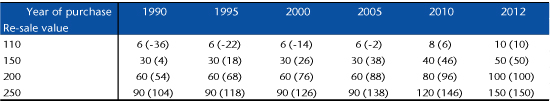

The following table shows the tax base according to the allowance system and the change in the real value of the capital (in parentheses) based on the re-sale value and on the date of acquisition for a good acquired for a value of 100 and re-sold in 2012.

Note on interpretation: For a good purchased at 100 in 1990 and resold at 110 in 2012, the tax base after deduction of 40% is 6 while the change in the real value of the capital is -36, given inflation. While the economic income is negative (there is a loss of purchasing power), with the allowance system the tax base increases. For a good purchased at 100 in 2005 and resold at 250 in 2012, the tax base after deduction is 90, while the change in the real value of the capital is 138: the allowance system is very favourable when the gain is large.

The tax base should be the capital gain after taking into account the inflation tax (variation in the real value of the capital). But this tax base should not be directly subject to a progressive tax scale. Gains on disposals are in fact deferred and should be subject to a charge equivalent to that on a regular income throughout the ownership period. Smoothing with a quotient that varies with the holding period deals with this point. This kind of system divides the income by the number of years held [1], applying the progressive scale to this “regular income equivalent”, while adding the household’s other income for the current year, then multiplying the increase in the tax related to the exceptional income by the number of years held [2]. An alternative is to tax the capital gains upon disposal at a constant rate equal to the principal marginal rate (30%, to which should be added the CSG wealth tax).

The following points need to be added to the comments above:

- General clearing systems between gains and losses over a long period (currently10 years) make it possible to take into account risks and potential losses, at least for diversified investors;

- As income from employment can easily be converted into capital income (through various financial instruments and portage arrangements), aligning the two taxes could limit the temptations of tax optimization, which opens the door to tax avoidance;

- In this respect, an Exit Tax, based on the unrealized capital gains, could be used to minimize the interest of becoming a tax exile, which increases with accumulated gains and tax potential.

Donations, especially when they are made outside inheritance, should not be used to erase capital gains, as is currently the case. This provision, which was initially intended to avoid double taxation, can now be used to completely escape taxation.

[1] Based on the equivalence of tax treatment for a regular income and an exceptional income, it appears that the division is made using a coefficient that depends on the interest rate. In practice, for low interest rates, this coefficient is equal to the number of years of ownership.

[2] This calculation is equivalent to regular taxation over time if the household’s current earnings are representative of its income (assuming regular income) for the duration of ownership and if the tax schedule is relatively stable.