Labour force participation rates and working time: differentiated adjustments

By Bruno Ducoudré and Pierre Madec

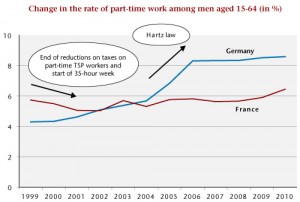

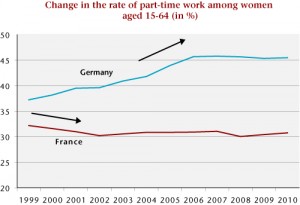

In the course of the crisis, most European countries reduced actual working time to a greater or lesser extent by making use of partial unemployment schemes, the reduction of overtime or the use of time savings accounts, but also through the expansion of part-time work (particularly in Italy and Spain), including involuntary part-time work. In contrast, the favourable trend in US unemployment is explained in part by a significant fall in the participation rate.

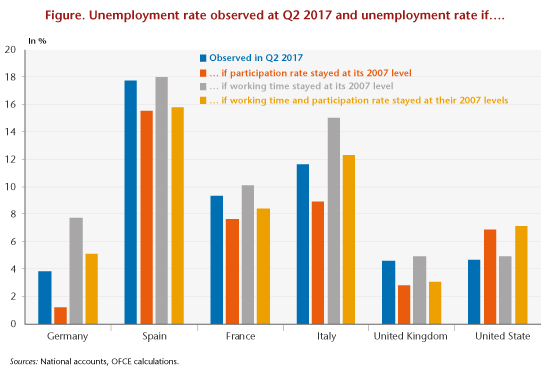

Assuming that, for a given level of employment, a one-point increase in the participation rate (also called the “activity rate”) leads to a rise in the unemployment rate, it is possible to measure the impact of these adjustments (working time and participation rates) on unemployment, by calculating an unemployment rate at a constant employment level and controlling for these adjustments. In all the countries studied, the active population (employed + unemployed) increased by more than the general population, except in the United States, which was due in part to pension reforms. Mechanically, without job creation, demographic growth results in increasing the unemployment rate of the countries in question.

If the participation rate had remained at its 2007 level, the unemployment rate would be lower in France by 1.7 points, by 2.7 points in Italy and by 1.8 points in the United Kingdom (see figure). On the other hand, without the sharp contraction in the US labour force, the unemployment rate would have been more than 3 points higher than that observed in 2016. Germany has also experienced a significant decline in unemployment since the crisis (‑5.1 points) even though its participation rate increased by 2.2 points. Given the same participation rate, Germany’s unemployment rate would be… 1.2%. However, changes in participation rates are also the result of structural demographic factors, meaning that the hypothesis of a return to 2007 rates is arbitrary. For the United States, part of the decline in the participation rate can be explained by changes in the structure of the population. The underemployment rate might well also be overstated.

As for working time, the lessons seem very different. It thus seems that if working time had stayed at its pre-crisis level in all the countries, the unemployment rate would have been 3.9 points higher in Germany, 3.4 points higher in Italy and 0.8 point higher in France. In Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States, working time has not changed much since the crisis. By controlling for working time, the unemployment rate is therefore changing along the lines seen in these three countries.

It should not be forgotten that there is a tendency for working time to fall, which is reflected in developments observed during the crisis independently of the specific measures taken to cushion the impact on employment through mechanisms such as short-time working or the use of time savings accounts. Since the end of the 1990s, working time has fallen substantially in all the countries studied. In Germany, between 1998 and 2008, it fell by an average of 0.6% per quarter. In France, the switch to the 35-hour work week resulted in a similar decline over the period. In Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States, average working hours fell each quarter by -0.3%, -0.4% and -0.3%, respectively. In total, between 1998 and 2008, working time declined by 6% in Germany and France, 4% in Italy, 3% in the United Kingdom and the United States and 2% in Spain, which was de facto the only country that during the crisis intensified the decline in working time begun in the late 1990s.