High-impact economists

By Zakaria Babutsidze and Mark J. McCabe

This coming Monday, October 14 2013, as many as three economists will join the elite group of winners of the Sveriges Riksbanks Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences is responsible for the selection of the Laureates in Economic Sciences from among the candidates recommended by the Economic Sciences Prize Committee. In early October, the Academy selects the laureates through a majority vote.

Presumably, the main criterion for awarding this prize is the impact that the winner(s) have had on society.[1] Clearly the assessment of such an impact is not an easy and straightforward matter. It involves approaching the problem from a variety of perspectives, some more objective than others. It is probably safe to assume that researchers, whose work has had a large impact on society, have also influenced the discipline of economics.

In this post we report some statistics in order to assess different economists’ impact on the discipline. To do this, we use data from 48 peer-reviewed journals in Economics and Finance. Each of these journals has published at least five articles authored by one or more of the prize winners between 1969 and 2012 The data is collected from Thomson Reuters’ ISI Web of Science and contains all articles published in these 48 journals starting in 1956 and ending in 2012, and all citations to each of these articles up to (and including) 2012.

The impact of a researcher is often measured by the number of citations his or her work has generated, e.g. the average annual number of citations to each article, weighted by the number of authors. This measure allows us to compare (albeit imperfectly) articles published at different points in time. However, for the case at hand, we are interested in the long run (or total) impact of the researcher. Therefore, our guiding indicator will be the total number of citations generated by the works of an economist weighted by the number of authors.

[Note: In identifying the pool of researchers eligible for the 2013 Prize, we excluded all past winners and, following the Academy’s guidelines, any other scholars who are now deceased.]

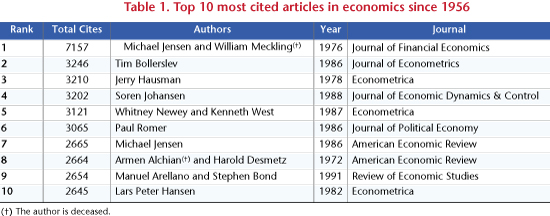

To get a sense of the citation impact of individual papers, take a look at Table 1, which lists the top 10 most cited articles in economics not authored by any prior prize winners. Although this provides an incomplete picture of a researcher’s total career impact, the Academy normally cites influential papers in the press releases (and explanatory materials) announcing the winners.

Table 1 features 11 economists that are eligible for the prize. Out of these 11 only one, Michael Jensen, has two papers in top 10. The table also demonstrates the large gap between the citation numbers of papers ranked first and second.

In what follows we present a researcher or career-level analysis. We assess the impact in two different ways. One approach utilizes all of the papers authors have written in their careers up to 2012 (this is a set comprising more than 170,000 papers). Our other approach is to utilize only the highest-impact papers (the top 100 most cited papers ever written).[2]

Before presenting the list of the most cited economists we first attempt to assess the power of the exercise. Namely, we ask what is the chance that people with high impact, as measured by number of citations, actually get awarded the prize? To answer this we take the top 25 most cited researchers according to each of the two criteria defined above (using all articles and the top 100 most cited articles) and see how many of those 25 have actually been awarded the prize. It turns out that in each case 13 out of 25 researchers have already won the prize.[3][4] These results suggest that number of citations received by researchers is a reasonable proxy for impact as defined by the Academy.

Next, the list of top 10 economists that are eligible for the Nobel Prize this year is presented in table 2. Panel A utilizes all articles in our dataset. Panel B of the table presents results using only the top 100 most cited articles. The columns titled Rank report the rank of the economist in the given list. The Total Rank columns refer to the rank of the economist in the list of high-impact economists that includes authors who have won the prize and those who are deceased. The Citations columns reports the total number of citations associated with the relevant set of articles by the author, weighted by the number of authors (e.g. if an article, authored by n authors, received z citations, then each listed author is credited with z/n citations).

As one can see from the table 2, eight economists appear in both of the lists. Five out of this eight are also featured in Table 1. These eight people are outstanding researchers by our measures and will most likely be among the economists considered for the 2013 prize.

The exercise that we have reported here measures the researchers’ impact on the discipline. However, the main guiding principle behind the Economic Science Prize is the impact on society. These two do not perfectly correlate. To see this, consider last year’s prize winners – Alvin Roth and Lloyd Shapley. They were awarded the prize “for the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design”. Their work has generated significant social benefits. For example, Roth is a co-founder of the New England Program for Kidney Exchange, which enables organ transplantation where it otherwise could not be accomplished. However, if we apply our measures to Roth and Shapley, their performance is not outstanding. None of them have authored an article that enters the list of 100 most cited articles in economics; therefore they do not figure in our rankings using this particular methodology. When we consider all articles, Roth ranks 99th, while Shapley ranks 979th.

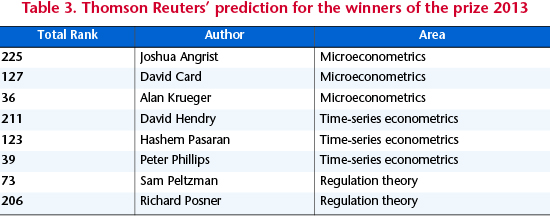

Postscript: In the discussion above, our primary intention is not to predict Monday’s winners. Nevertheless, it seems that the Economic Sciences Prize Committee selects a sub-discipline, or a narrow research area to recognize and only after this selects candidates who have contributed to the advancement in that area the most. Recall that we provided an analysis of total citations. We have not performed any breakdown by research areas and have not modeled the Committee’s area selection process. In contrast to our work, area selection is an important component of the well-known efforts by the Intellectual Property and Sciences business of Thomson Reuters to predict winners of the Economics Science Prize. This year they predict that one of the following three areas are likely to be honored by the Academy: microeconometrics, time-series econometrics or regulation theory.[5] In each of these three areas they predict two or three winners. In the table below, without further comment, we provide the list of people they predict to win the Nobel Prize alongside with their ranks in our high-impact economists list.

[1] In selecting a winner for the Economic Science Prize, the Swedish Academy follows the same principle that is used in awarding the five original Nobel Prizes, namely choosing those individuals, “…who have conferred the greatest benefit to mankind.”

[2] Book chapters and working papers are not included in our dataset.

[3] However, the identities of the 13 prize winners is somewhat different across the two procedures. When all articles are considered, the 13 winners among the top 25 most highly cited authors are (in decreasing order of importance): Becker, Lucas, Heckman, Stiglitz, Engle, Merton, Kahneman, Solow, Arrow, Granger, Akerlof, Krugman, Williamson. When the set of the top 100 articles is considered, the 13 winners are Engle, Becker, Heckman, Kahneman, Solow, Coase, Akerlof, Lucas, Arrow, Granger, Sharpe, Black and Scholes.

[4] Note that the lists also include a number of influential economists who died without winning the prize. These include Zvi Griliches, William Meckling, Charles Tiebout, Amos Tversky and Halbert White.

[5] It is noteworthy that seven of the 10 papers listed in table 1 are in the general area of econometrics.