by Christine Rifflart

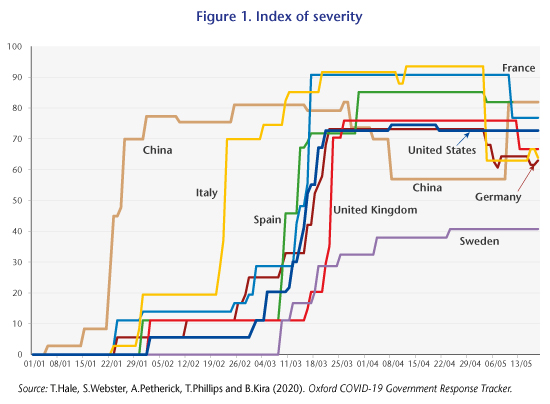

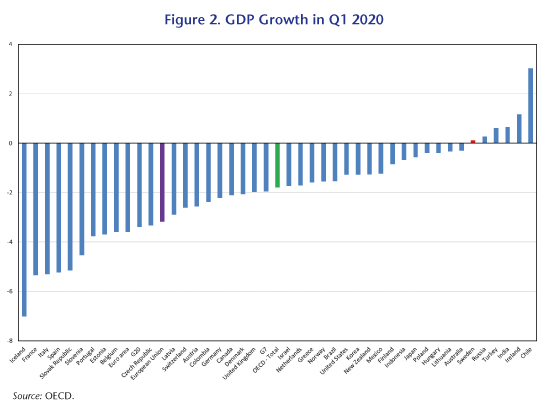

Spain has been hit hard in 2020 by the Covid-19 health

crisis, which the authorities are struggling to control, accompanied by an

economic recession that is one of the most violent in the world (GDP fell by

11% over the year according to the INE)[1]. The country’s unemployment rate reached 16.1% at

the end of last year, a rise of 2.3 points over the year despite the

implementation of short-time work measures. The public deficit could exceed 10%

of GDP in 2020, and the public debt could approach 120% according to the Bank

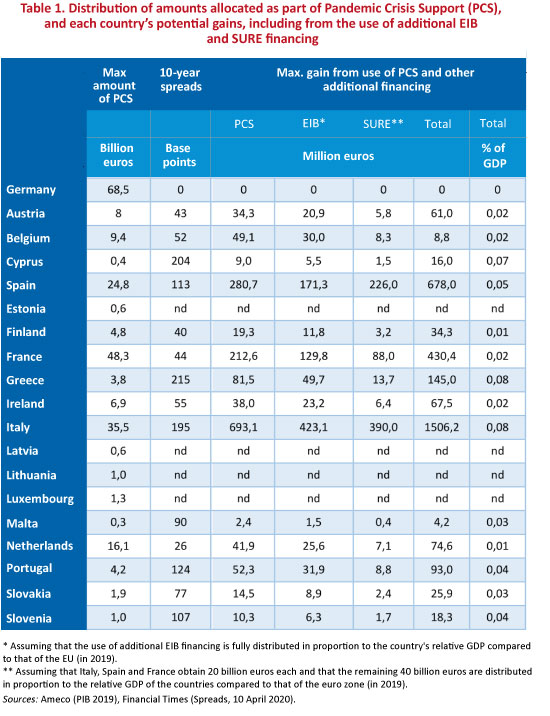

of Spain’s January 2021 forecasts. Europe has enacted large-scale support programmes

for affected countries, and as one of these Spain will be the country receiving

the most EU-level aid. It will benefit from at least 140 billion euros, with 80 billion

of that (i.e. 6.4% of 2019 GDP) taking the form of direct transfers through the

NextGenerationEU programme.

This aid is arriving in a very particular political

context, marked by the progressive aspirations of a coalition government

(PSOE-Unidas / Podemos) that has governed for just over a year, and which still

appears to be solid. The commitments made in December 2019 between the two

parties in a joint Pact entitled ”Coalicion Progresista –

Un nuevo acuerdo para Espana” [Progressive

Coalition – A New Agenda for Spain] have now been included in the recovery plan

sent to the EU Commission, and the first measures of the planned reforms have

been included in the 2021 budget. In this difficult health and economic

situation, the Spanish government could seize the opportunity provided by this

crisis to carry out a thorough restructuring of the country with the help of

European funds and push through some of the social reforms announced in the

PSOE-UP Pact. The needs, it must be said, are great. In 2018, the poverty rate

was 19.3% among young people and 10.2% among those over 65 (compared with 11.7%

and 4.2% respectively in France). Even though annual growth averaged close to

3% over the period 2015-2019, Spain’s unemployment rate has remained at a very

high level (14.1% in 2019), and labour productivity is still almost 25% lower

than in France. There are significant regional disparities and insufficient investment,

particularly public investment. But Spain could turn the corner over the next

few years. The measures announced are commensurate with the government’s

ambitious aspirations for growth, employment, and social equity. The greater risk

is probably to the government’s solidity and its political capacity to

implement it.

The 2021 budget, the first since July 2018!

Spain has gone two years without a budget vote, as

the 2018 budget was extended twice after being amended by government decrees. But

the government has finally managed to provide itself with a 2021 budget while

impeccably respecting the timetable it had set out. The budget was sent to Brussels

on 10 October 2020, approved on 3 December by the Congress of Deputies (Spain’s

lower chamber), and on 22 December by the Senate, and so was adopted in less

than three months. However, nothing can be taken for granted. The latest legislative

elections in November 2019 (the fourth in four years) failed to give an

absolute majority in Parliament to the socialist party PSOE, or even to the leading

two parties combined (i.e. PSOE-UP, 155 deputies out of 350). So Pedro

Sanchez’s coalition government was compelled to seek the support of the small

pro-independence and regionalist parties for the adoption of its budget. After

three months of negotiations and several thousand amendments, a large majority

was obtained. Of the 350 deputies in Congress, 188 from 11 different political

formations voted in favour (155 from PSOE-UP, 13 from the ERC and 6 from the

PNV). It must be said that a political failure would have been very unwelcome

given the great needs and expectations and the favourable opportunities.

European funding to carry out the modernization of Spain’s

production infrastructure, as set out in the PSOE-UP Pact of December 2019

According to Spain’s Finance Minister [2], the country is expected to receive 79.8 billion

euros in European subsidies over the period 2021-2023 under the NextGenerationEU programme. This is over 10 billion

more than the amount announced by the Commission in the spring of 2020 (69.4

billion, a revision of +14.9%), as the 2020 growth forecasts made last autumn were

more pessimistic than those made six months earlier, and due to converting the initial

funding from 2018 prices to current prices. The revision concerns the

allocation of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), which has increased

from 59.2 billion euros to 69.5 billion, with the grant under the REACT EUprogramme remaining at 10.3 billion. Spain is

thus now the largest recipient of EU funds, ahead of Italy, which is to receive

79.6 billion (up from 76.1 billion initially announced), i.e. 4.4% of its 2019

GDP, 2 points less than Spain. Seventy percent of this allocation is guaranteed

for 2021-2022 (46.6 billion) [3]. The balance over 2023 will have to be reassessed

in June 2022, depending on the economic situation and the state of public

finances in the light of the Stability and Growth Pact rules, which are likely

to be restored by that date.

In order to benefit from European funds, Spain,

like all its partners, has to present its National Plan for Recovery,

Transformation and Resilience, which aims to stimulate short-term growth

through investment and consumption [4],

and to promote a “more sustainable, more resilient economy that

is prepared for the challenges ahead”,in thewords

of the Commission. Ultimately, the government’s objective is to raise potential

growth by 0.4-0.5 percentage points to over 2% per year by 2030.

While Spain traditionally has a low rate of

absorption of European funds, this time the government wishes to speed up the

process greatly. So on 20 January (with a deadline set for 30 April), the

government submitted to Brussels the 30 files in its Recovery plan presenting

the investment projects and the guidelines for the reforms envisaged in the

areas of taxation, the labour market, and pensions, which are intended to

ensure the country’s transition. It even foresees anticipating the release of

the RRF funds (scheduled after the Commission examines the Recovery plan for two

months) by financing the investments with debt. It must be acknowledged that

the needs are immense in Spain’s production system, which is marked by the

importance of SMEs. At the end of 2019, 53.5% of businesses were made up of the

self-employed, 40% had between 1 and 9 employees, and 5.5% had between 10

and 49 employees, in total accounting for half of all jobs. According to the

government’s intentions:

- 37% of the funds are earmarked for the ecological transition

(250,000 new vehicles purchased by 2023, installation of 100,000 charging

stations, transformation of the electrical system to 100% renewable energy

by 2050, and the renovation of more than 500,000 homes for improved energy

efficiency);

- 34% are for the digital transformation (with a coverage rate of 80%

of the population, including 75% by 5G; development of teleworking for

more than 150,000 public jobs; training for more than 2.5 million SMEs;

etc.);

- And 30% for Research and Development, education and training, and social

and territorial inclusion.

The broad outlines of the reforms have also been

drawn up. The new orientation of the tax reform aims at greater progressiveness

and more redistribution [5], and is already included in the 2021 budget (see

below). The reforms concerning the labour market, which is still very dual, and

pensions have not yet been discussed in Parliament or with the social partners,

so they are still at the stage of principles, which should, nevertheless,

satisfy Brussels. As regards labour market reform, the main measures presented

aim at generalizing the use of open-ended contracts and tightening up on the

use of fixed-term contracts; strengthening the use of flexible working time as

an alternative to fixed-term contracts and redundancies; the modification of active

employment policies; calling into question the 2012 reform on collective

bargaining; an employment programme targeted at young people (2021-2027); and modernizing

the public employment service (SEPE). The pension reform is less advanced and

is giving rise to greater tension between the partners. For example, in the

plan sent to Brussels the government did not include its proposal to increase

the contribution period for calculating pensions from 25 to 35 years.

Above all, however, Spain’s National

Plan for Recovery, Transformation and Resiliencepresented to the

European Commission, which should lead to the disbursement of European funds,

is fully in line with the Coalicion Progresista – Un nuevo acuerdo para Espana Pact signed in December 2019 between the two ruling

coalition parties PSOE and UP-Podemos. The document’s initial sections stress

the importance of investing in the digital transformation, the ecological

transition, and R&D and training to modernize Spain’s economy and create

quality jobs. The European grants provide the left-wing government with a giant

opportunity to finance this project to transform Spain’s productive infrastructure.

Higher taxation to finance the social measures

included in the Pact

In addition to the investment projects included in

the recovery plan and financed by European funds, in its 2021 budget the

government launched the tax reform presented in the Pact, which is intended to

finance the social measures planned or already taken. As mentioned above, the

absence of a majority in the Congress of Deputies and the Senate has opened the

way for negotiations with the small pro-independence and regionalist parties,

and thus for concessions to obtain support. Not all the measures were approved [6]. Ultimately, the reform should bring in 7.7

billion euros [7], 1.4 billion less than what was set out in the budget

bill sent to Brussels. If we add the cost of maintaining VAT on surgical masks

at 0%, the shortfall to meet the deficit commitment comes to 3 billion euros.

The 2021 tax reform mainly focuses on large corporations

and high income earners. It includes:

- Reducing

the corporate tax exemption on dividends and capital gains received from foreign

subsidiaries from 100% to 95%. So

now the 5% not exempted is taxed at the general rate of 25% (30% in the

case of banks and oil companies). This measure excludes SMEs (companies

with a turnover of less than 40 million) for three years (expected gain of

1,520 million euros). In addition, the State has introduced a minimum tax

on listed real estate investment companies (SOCIMIs) of 15% (+25 million

euros);

- A

2-point increase in personal income tax (IRPP) on income over €300,000 and 3 points on

savings income over €200,000 (raising the rate from 23% to 26%) (a total gain

of €490 million). This measure affects the 36,200 individuals with the

highest incomes (i.e. according to the Ministry, 0.07% of contributors) [8];

- A reduction from 8,000 to 2,000 euros in the IRPP exemption

threshold for individual investments in private pension funds (+580

million) and an increase from 8,000 to 10,000 euros in the incentive

threshold for companies;

- The tax on insurance premiums has been increased from 6% to 8%

(+507 million);

- An increase in VAT on sugary and

sweetened drinks, excluding dairy products, from 10 to 21%

(expected gain of 360 million);

- The introduction of a 0.2% financial transaction tax for

corporations with a capital of more than €1 billion (Tobin tax) anda 3% tax

on the digital economy (GAFA tax).

These taxes should bring in €850 million and €968 million respectively.

Adopted in 2020, they came into force on 16 January;

- A green tax is being introduced with the creation of

a tax on single-use plastics (+491 million) along with other measures (tax

on waste, etc.) (+861 million);

- Lastly, measures to combat tax fraud are being

taken, with an expected gain of 828 million.

This additional tax revenue is intended to cover

social expenditure, in particular the Minimum Living Income introduced

in June 2020 to reduce poverty and promote labour market integration. This will

affect around 850,000 families (2.3 million people, 17% of the population). The

amount of support ranges from 462 euros per month for a person living alone to

1,015 for a family. The pensions and salaries of civil servants will be increased

by 0.9%, non-contributory benefits by 1.8%, and the reference indicator used to

determine eligibility for many social benefits (IPREM) by 5% (it has been

frozen since 2017). The other flagship measure concerns dependency support, with anadditional

600 million, and education. On the other hand, the goal

of raising the minimum wage (SMI) to 60% of the average wage by the end of the

legislature (to between €1100 and €1200 per month in 2023) has been temporarily

suspended. After a 20% increase in 2020, the SMI therefore remains at €950 per

month for 14 months. The salaries of members of the executive have been frozen

this year.

After long years of political instability, it is to

be hoped that, despite the difficult context, the current coalition government

will be able to continue to find a basis for agreement within the different

Spanish political formations in order to take advantage of the favourable

opportunities and open up new and constructive perspectives.

[1] For a more detailed analysis of the crisis, please

refer to the OFCE Policy Brief by Hervé Péléraux and Sabine Le

Bayon: “Croissance mondiale confinée en 2020”, no. 82 of 14 January

2021.

[2] The

information must be approved by the European Parliament in the coming weeks.

[3] The distribution of these new amounts over

2021 and 2022 is not available. We do know, however, that of the 69.437 billion

initially planned for the period 2021-2023, the State was to receive 26.634

billion in 2021, including 2.436 billion from the REACT EUfund for

the purchase of vaccines. Out of the 26.634 billion received, the State is to disburse

10.8 billion to the regions, which are also to receive 8 billion REACT EU funds to strengthen their health and education systems.

[4] On the basis of an average multiplier of 1.2,

in the budget bill sent to Brussels the government estimated the impact of the

recovery plan on growth at 2.5 points in 2021. Under less favourable hypotheses

(the rather slow rate of absorption of past European funds, complexity in

management at the regional level, etc.), in January 2021 the Bank of Spain

estimated the impact at between 1 and 1.6 points.

[5] According to the OECD, in 2018, the ratio

between the average income of the richest 20% and the poorest 20% was 5.9 in

Spain, compared to 4.6 in France.

[6] Thus, the tax increase on private educational

and health institutions was rejected before it was even presented to the

Congress of Deputies, and the tax increase on diesel (+3.8 cents per litre to

34.5 cents, compared to 40.07 on petrol) had to be abandoned. These measures

were expected to bring in 967 and 500 million euros respectively.

[7] Using the cash concept, the revenue changes from

6.847 billion to 5.635 billion in 2021 and from 2.323 billion to 2.135 billion

in 2022.

[8] This measure reflects a fairly marked retreat

from the Pact’s commitments. Indeed, the IRPP was expected to increase by 2

points on income > €130,000, by 4 points on income > €300,000, and by 4

points on savings income > €140,000. An increase of 1 point in the wealth

tax was included for assets over €10 million.