Faced with a rapid and explosive deterioration in their public accounts, the industrialized countries, particularly in Europe, have implemented large-scale austerity policies, some as early as 2010, in order to quickly reduce their deficits. In a situation like this, several questions about France’s fiscal policy need to be examined:

– First, has France made a greater or lesser fiscal effort than other OECD countries to deal with its public accounts?

– Second, is there a singularity in the fiscal austerity policy implemented by France and has it had more or less effect on growth and the level of unemployment?

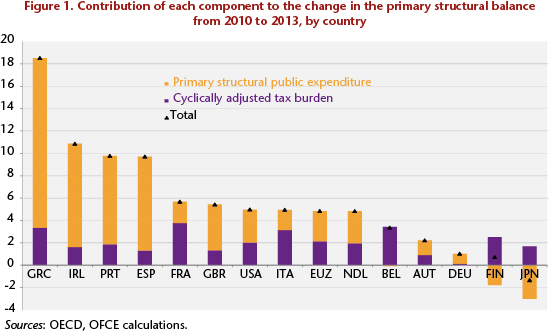

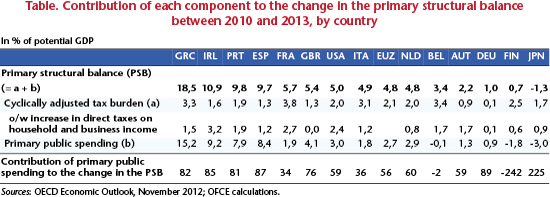

With the notable exception of Japan, between 2010 and 2013 all the major OECD countries implemented policies to reduce their primary structural deficits [2]. According to the latest OECD figures, these policies represented a fiscal effort of about 5 percentage points of GDP over three years on average in the euro zone, the United States and the United Kingdom. In contrast, the differences within the euro zone itself were very large: they range from only 0.7 percentage points in Finland to more than 18 points in Greece. Among the major industrialized countries of the OECD, France is, after Spain, the country that has made the greatest fiscal effort since 2010 from a structural viewpoint (5.7 percentage points of GDP over three years). In the post-World War 2 era, France has never experienced such a brutal and sustained adjustment in its public accounts. For the record, the budget effort that took place in the previous period of sharp fiscal consolidation from 1994 to 1997 was twice as small (a cumulative negative fiscal impulse of 3.3 GDP points). Between 2010 and 2013, the cyclically adjusted tax burden increased in France by 3.8 GDP points, and the structural effort on public spending represented a gain of 1.9 GDP points over four years (Figure 1). Among the OECD countries, it was France that made the greatest cyclically adjusted increase in the tax burden in the period 2010-2013. Finally, from 2010 to 2013, the structural effort to reduce the public deficit broke down as follows: two-thirds involved an increase in the tax burden and one-third came from public spending. This breakdown is different from that observed on average in the euro zone, where the fiscal effort over the period 2010-13 involved a nearly 60% reduction in public expenditure, rising to over 80% in Spain, Portugal, Greece and Ireland. In contrast, in Belgium, the entirety of the fiscal effort came from a higher tax burden. And in the case of Finland, primary structural public spending in points of potential GDP rose over the period 2010-2013, which was more than offset by the increase in the tax burden.

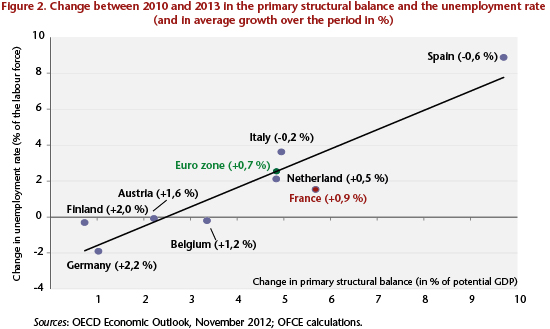

While France’s substantial budgetary efforts have undeniably had a negative impact on economic activity and employment, it is nevertheless true that the budget decisions of the various governments since 2010 appear to have affected growth and the labour market relatively less than in most other countries in the euro zone. Within the euro zone-11, from 2010 to 2013 only four countries – Germany, Finland, Austria and Belgium – experienced average growth of over 1% per year, with unemployment rates that not only did not increase, but occasionally even fell. However, these are also the four countries that made the smallest reductions in their structural deficits over this period. France, on the other hand, is among the countries that made the greatest structural effort since 2010, and it has simultaneously managed to contain the rise in unemployment to some extent. Indeed, compared with the Netherlands, Italy and the euro zone average, France’s fiscal policy was more restrictive by about 1 GDP point from 2010 to 2013, yet the unemployment rate increased by 40% less than in the Netherlands, 60% less than the euro zone average and more than two times less than in Italy. Likewise, growth in France was higher on average over this period: 0.9% per year, against 0.5% in the Netherlands, 0.7% in the euro zone and ‑0.2% in Italy.

Why has the French fiscal contraction had less impact on growth and employment than in most other countries? Beyond the economic fundamentals, some evidence suggests that the budget decisions of the successive governments since 2010 may have led to fiscal multipliers that are lower than in the other countries. After Finland and Belgium, France is the country where public spending played the smallest role in reducing the structural deficit. As illustrated by recent studies, in particular the IMF study and the article signed by economists from the central banks in Europe and the U.S., the European Commission, the OECD and the IMF, targeting fiscal adjustment through raising the tax burden rather than cutting public spending has given France smaller short-term fiscal multipliers than those observed in countries that have made the opposite choice (Greece, Portugal, Ireland and Spain). In the case of France, nearly 50% of the fiscal adjustment was achieved by an increase in the direct taxation of household and business income (Table 1). And as has also been the case for the United States, Belgium and Austria, which achieved between 50% and 75% of their fiscal adjustment by increasing direct taxation, it seems that these countries have also done best at maintaining their growth in the face of the budget cuts. Conversely, the ones that have used this lever the least in their fiscal adjustments are the southern European countries and the Netherlands.

[1] This post makes use of certain parts of the article published in Alternatives Economiques, M. Plane, “L’austérité peut-elle réussir en France ?”, Special issue no. 96, 2nd quarter 2013.

[2] The primary structural deficit measures the structural fiscal effort made by general government (les administrations publiques). It corresponds to the public balance, excluding interest charges, that would be generated by the government if the GDP of the economy were at its potential level. This measure is used to adjust the public balance for cyclical effects.