By Jérôme Creel and Xavier Ragot

The weakness of the recovery in 2014 and 2015 raises the need for a structural re-examination of the state of France’s productive fabric. Indeed, an analysis of investment dynamics, the trade balance, productivity gains and business margins, and to a lesser extent companies’ access to credit, indicates the existence of some disturbing trends since the early noughties. In addition, the persistence of the crisis inevitably poses the question of the unravelling of France’s productive fabric since 2007 due to a combination of low growth, weak investment and numerous bankruptcies.

The contributions gathered in Revue de l’OFCE no.142 have a double ambition: first, to put France’s businesses and economic sectors at the heart of reflection about the ins and outs of the current slowdown in growth, and second, to question the basis for theoretical analyses of future growth in light of the situation of France and Europe. Based on the various contributions, nine conclusions emerge:

1) Growth potential, a concept that aims to measure an economy’s medium-term productive capacity, has fallen in France since the crisis. While the level of potential growth is high over the long term, on the order of 1.8%, it has fallen since the crisis by about 0.4 point, according to the new measurement provided by Eric Heyer and Xavier Timbeau.

2) The main point is to figure out whether this slowdown is temporary or permanent. This is important for growth forecasts but also with respect to France’s European commitments, which depend on its growth potential. One important conclusion is that a very large portion of the current slowdown is transitory and linked to France’s economic policy. As Bruno Ducoudré and Mathieu Plane demonstrate, the low level of investment and employment can be explained by the macroeconomic environment and in particular by the current sluggish economy. Business behaviour does not seem to have changed during the crisis. The analysis by Ducoudré and Plane also shows that the determinants of investment differ in the short term and the long term. A 1% increase in economic activity increases investment by 1.4% after one quarter, whereas a 1% increase in the margin rate has very little impact in that same period. However, over the long term (10 years), a 1% increase in activity boosts investment by about 1%, while a 1% increase in the margin rate boosts investment by 2%. So promoting investment means supporting economic activity in the short term, while boosting margins will have an impact over the longer term.

3) France’s productive fabric will take time to recover from the effects of the crisis because of three major obstacles: the weakness of investment, of course, but also the decline in the quality of investment and finally the disruption of production following on from the poor allocation of capital during the crisis, including its territorial dimension. Sarah Guillou and Lionel Nesta show that the low level of investment makes it impossible to go upmarket, which has meant less technical progress since the crisis. Jean-Luc Gaffard and Lionel Nesta then show that regional convergence has slowed since the crisis, and that economic activity has tended to decline in the most productive areas.

4) The concept of growth potential as a tool for macroeconomic management has emerged from the crisis in a profoundly weakened state. Whatever the methods used, ongoing revisions of growth potential make the idea of a system of rules-based European guidance dangerous, according to Henri Sterdyniak. There is a need to rediscover European economic policy that is discretionary in character. In addition, fiscal policy that is more contingent on macroeconomic and financial conditions needs to be better coordinated with the climate issue, as Jérôme Creel and Eloi Laurent argue.

5) The notion of secular stagnation, that is to say, a lasting weakening of growth, has led to intense debate. Two visions of secular stagnation are discussed. The first vision, associated with Robert Gordon, insists that technological progress has been exhausted. The second flows from the analysis of Larry Summers and stresses the possibility of a permanent demand deficit. Jérôme Creel and Eloi Laurent show the limitations of the analysis of Robert Gordon for France; in particular, French demographics are more an advantage for French growth than a hindrance. Gilles Le Garrec and Vincent Touzé show the possibility of a long-term demand deficit that would hinder capital accumulation, due to the central bank’s inability to make further interest rate reductions. In this kind of environment, support for demand is necessary to get out of an unfavourable equilibrium between low inflation and high unemployment, which leads to a negative perception of growth potential. Changing expectations may require large-scale policies to stimulate economic activity, along with an acceptance of high inflation over the long term.

6) The analyses presented here therefore recognize the profound difficulties with France’s productive fabric and recommend better coordination of public policy. Support for demand is needed rapidly in order to restore investment, followed by an ongoing progressive policy to boost the margins of companies exposed to international competition – so, according to Jean-Luc Gaffard and Francesco Saraceno, not a competitive shock, but rather support for business that takes into account the time profile of productive investment.

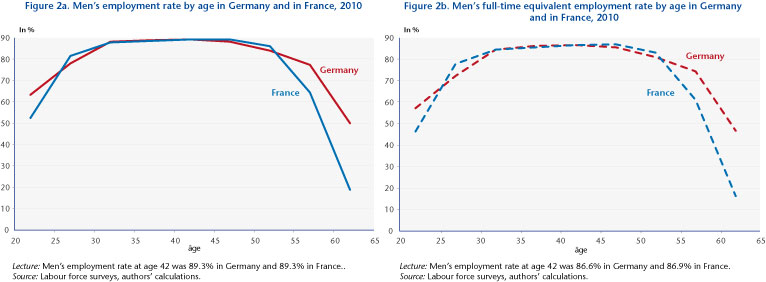

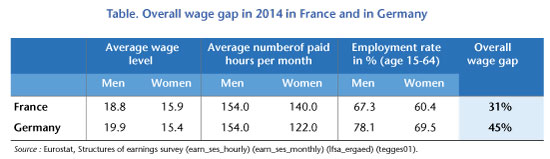

7) In the longer term, part of what can be characterized as the French supply-side problem is the result of poor European adjustments, including the discrepancy in wages between Europe’s major economies. The divergence between France and Germany since the mid-1990s has been impressive. Mathilde Le Moigne and Xavier Ragot show that German wage restraint is a singularity among European countries. They offer a quantification of the impact of this wage moderation on France’s foreign trade and economic activity, and conclude that German wage restraint has contributed to an increase of more than 2 points in France’s unemployment rate. A supply policy could also go by the name of a policy for European re-convergence.

8) The deep-going modernization of the productive fabric will depend on spaces for cooperation, collective learning and collaboration so as to nourish the creativity made possible by new technologies. These spaces need to recognize the importance of difficult-to-value intangible assets. In economies with an ageing workforce, advances in robotics and artificial intelligence should lead to enhancing potential productivity, according to Sandrine Levasseur. Cooperation also needs to be strengthened in two areas: the company and the territory. Within companies, partnership governance should help limit short-termist financial tendencies. With respect to territory, the definition of regional innovation systems should be the focus of a modern industrial policy, according to Michel Aglietta and Xavier Ragot.

9) Guillaume Allègre concludes that it is not so much the level of production that is disturbing as the inequitable distribution of the fruits of growth, however small these may be. The emerging consensus on the negative impact of inequality on economic growth should not obscure the real debate, which does not concern just the income gap, but also what that income makes it possible to consume, i.e. equal access to goods and services of equal quality. The key question is thus the content of production, more than simply growth.

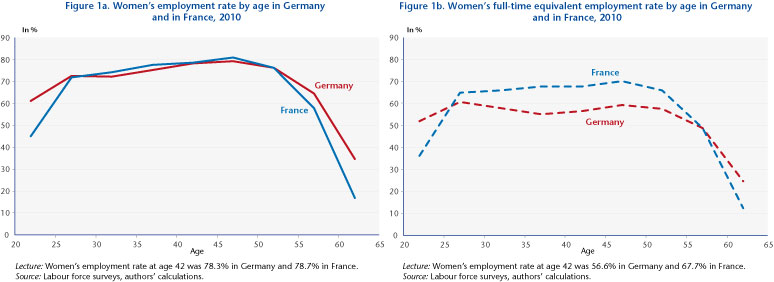

Thus policies aimed at occupational equality cannot leave aside the issue of working time and the quality of the jobs held by women. It seems that from this point of view France is doing better than Germany, although much remains to be done in this area.

Thus policies aimed at occupational equality cannot leave aside the issue of working time and the quality of the jobs held by women. It seems that from this point of view France is doing better than Germany, although much remains to be done in this area.