Euro zone: Recovery or deflation?

By Céline Antonin, Christophe Blot, Sabine Le Bayon and Danielle Schweisguth

This text summarizes the OFCE’s forecast for 2014-2015 for the euro zone economy

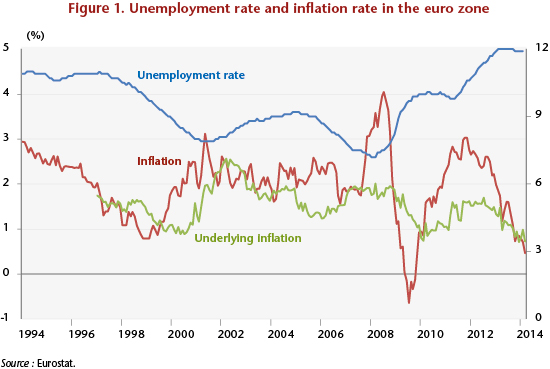

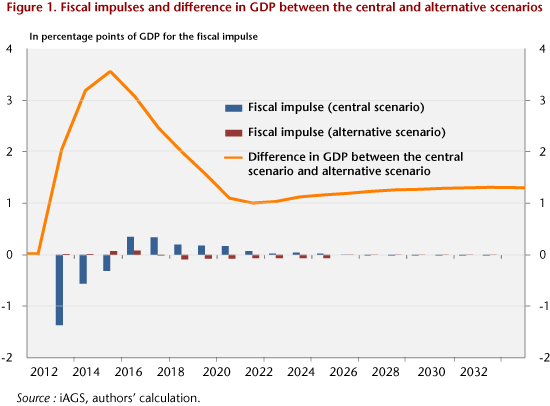

Will the euro zone embark on the road to recovery, or will it sink into a deflationary spiral? The latest macroeconomic indicators are sending out conflicting signals. A return to growth is being confirmed, with three consecutive quarters of rising GDP. However, the level of unemployment in the euro zone remains at a historically high level (11.9% for the month of February 2014), which is fuelling deflationary pressures, as is confirmed by the latest figures on inflation (0.5% yoy for March 2014). While this reduction in inflation is partly due to changes in energy prices, the fact remains that underlying inflation has fallen under 1% (Figure 1). In these conditions, a turnaround in inflationary expectations cannot be excluded, which would undoubtedly push the euro zone into deflation. The ECB has been concerned about this situation for several weeks and says it is ready to act (see here). However, no concrete proposal for a way to ease monetary policy and ensure that expectations are not anchored on a deflationary trajectory has been set out.

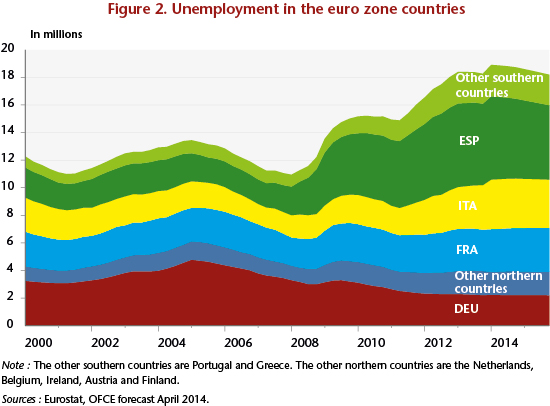

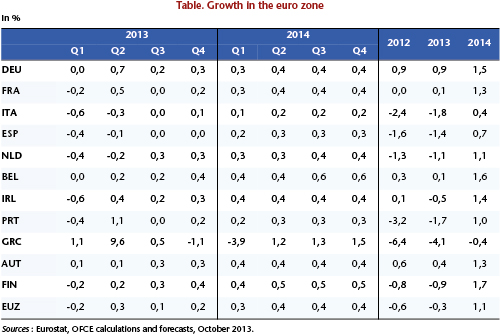

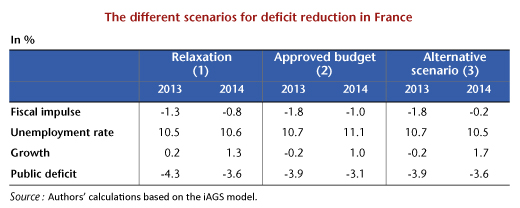

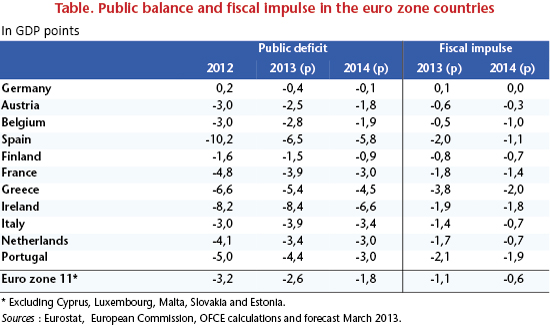

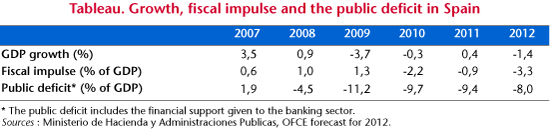

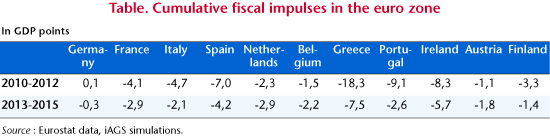

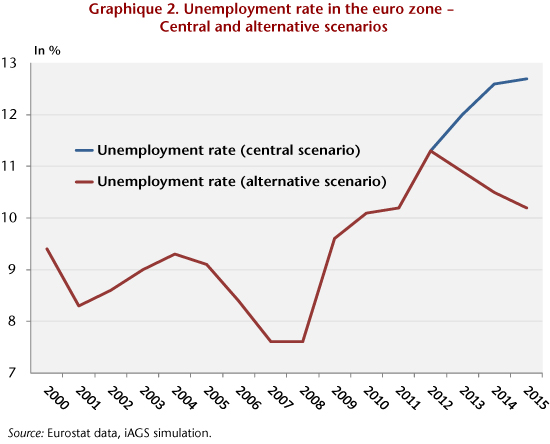

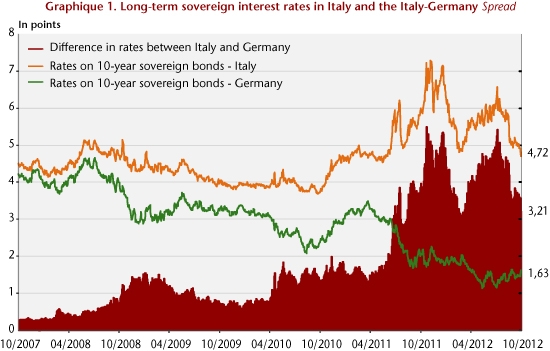

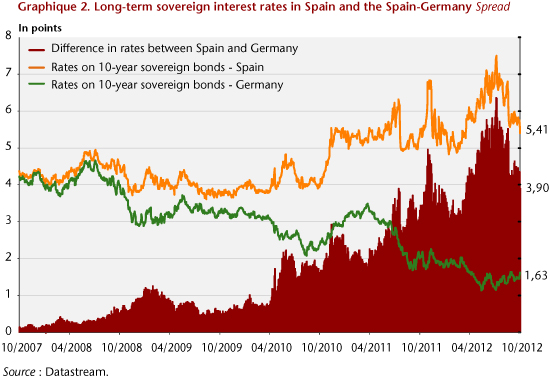

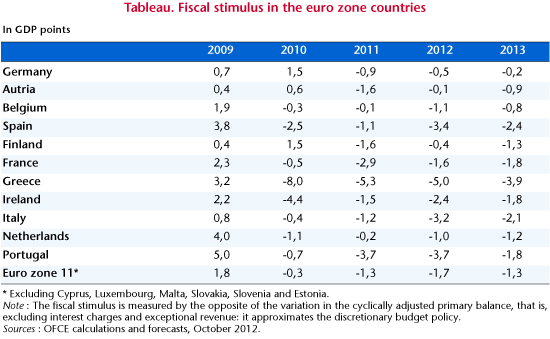

After a fall in GDP of 0.4% in 2013, the euro zone will return to positive growth: 1.3% in 2014 and 1.6% in 2015. Even so, at this rate of growth, there will still be an open output gap in most of the euro zone countries, reflecting the idea that the euro zone is only slowly pulling out of the crisis. Indeed, although efforts to reduce deficits will be curtailed, fiscal policies will still be pro-cyclical. Furthermore, financing conditions will continue to improve. The end of the sovereign debt crisis, thanks in particular to the announcements by the ECB in July and September 2012 [1], has reduced the risk premiums on the market for government bonds. The impact of lower long-term market rates has been partly reflected in bank interest rates, and credit supply conditions are generally less restrictive than they were between early 2012 and mid-2013. But there will still not be sufficient growth to trigger a recovery strong enough to lead to a rapid and significant reduction in unemployment. Indeed, the level will fall only very moderately, from 11.9% in the first quarter of 2014 to 11.3% at year end 2015. While Germany will enjoy almost full employment, mass joblessness in Spain and the other countries of southern Europe will persist (Figure 2). Unemployment should stabilize in Italy and continue to grow in France.

However, this continuing underemployment is giving rise to the risk of deflation. It is holding back growth in wages and contributing to the weakness of underlying inflation, which was in fact zero in Spain in March 2013 and negative in Greece and Portugal. For the euro zone as a whole, we do not expect deflation in the short term, but the weakness of growth is increasing the likelihood that private agents’ expectations are not anchored in a deflationary scenario.

The situation in the euro zone is reminiscent of Japan in the 2000s. The country began to experience deflation in 1999 [2] following the recession associated with the Asian crisis. At that point, despite average growth of 1.4% between 2000 and 2006, prices failed to pick up, and the country’s central bank did not find a way out of this trap, despite trying expansionary monetary policies. This is precisely the dynamic threatening the euro zone today, making it crucial to use all possible means to avoid this (monetary policy, fiscal policy and the coordination of wage policy [3]).

[1] In July, ECB President Mario Draghi declared that the central bank would save the euro “whatever it takes”. In September, the ECB announced the creation of a new mechanism called Outright Monetary Transactions (see the post by Jérôme Creel and Xavier Timbeau), which enables it to engage in unlimited purchases of sovereign debt.

[2] It should be pointed out that there was an initial period of deflation in 1995 following three years of economic stagnation.

[3] All these elements are discussed in detail in the previous iAGS report (2014).