The euro is 20 – time to grow up

By Jérôme Creel and Francesco Saraceno [1]

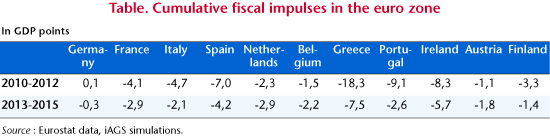

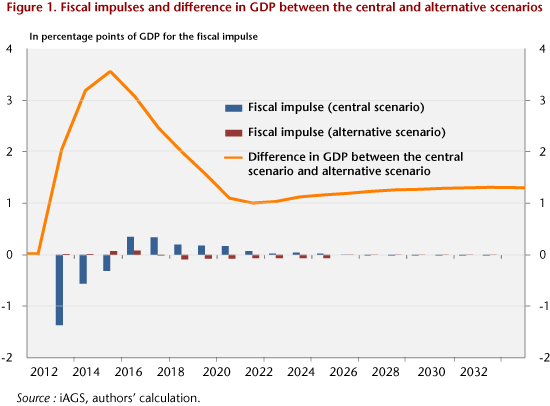

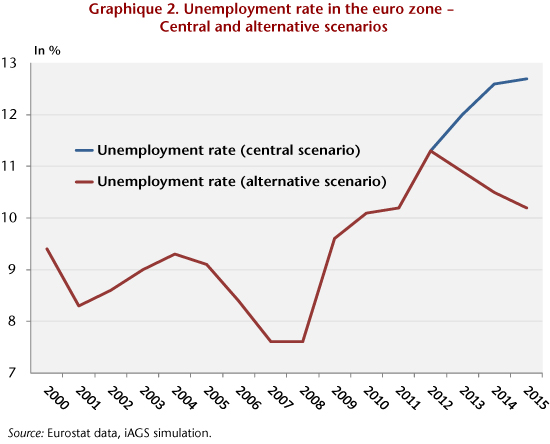

At age twenty, the euro has gone through a difficult adolescence. The success of the euro has not been aided by a series of problems: growing divergences; austerity policies with their real costs; the refusal in the centre to adopt expansionary policies to accompany austerity in the periphery countries, which would have minimized austerity’s negative impact, while supporting activity in the euro zone as a whole; and finally, the belated recognition of the need for intervention through a quantitative easing monetary policy that was adopted much later in Europe than in other major countries; and a fiscal stimulus, the Juncker plan, that was too little, too late.

Furthermore, the problems facing the euro zone go beyond managing the crisis. The euro zone has been growing more slowly than the United States since at least 1992, the year the Maastricht Treaty was adopted. This is due in particular to the inertia of economic policy, which has its roots in the euro’s institutional framework: a very limited and restrictive mandate for the European Central Bank, along with fiscal rules in the Stability and Growth Pact, and then in the 2012 Fiscal Compact, which leave insufficient room for stimulus policies. In fact, Europe’s institutions and the policies adopted before and during the crisis are loaded down with the consensus that emerged in the late 1980s in macroeconomics which, under the assumption of efficient markets, advocated a “by the rules” economic policy that had a necessarily limited role. The management of the crisis, with its fiscal stimulus packages and increased central bank activism, posed a real challenge to this consensus, to such an extent that the economists who were supporting it are now questioning the direction that the discipline should take. Unfortunately, this questioning has only marginally and belatedly affected Europe’s decision-makers.

On the contrary, we continue to hear a discourse that is meant to be reassuring, i.e. while it is true that, following the combination of austerity policies and structural reforms, some countries, such as Greece and Italy, have not even regained their pre-2008 level of GDP, this bitter potion was needed to ensure that they emerge from the crisis more competitive. This discourse is not convincing. Recent literature shows that deep recessions have a negative impact on potential income, with the conclusion that austerity in a period of crisis can have long-term negative effects. A glance at the World Economic Forum competitiveness index, as imperfect as it is, nevertheless shows that none of the countries that enacted austerity and reforms during the crisis saw its ranking improve. The conditional austerity imposed on the countries of the periphery was doubly harmful, in both the long and short terms.

In sum, a look at the policies carried out in the euro zone leads to an irrevocable judgment on the euro and on European integration. Has the time come to concede that the Exiters and populists are right? Should we prepare to manage European disintegration so as to minimize the damage?

There are several reasons why we don’t accept this. First, we do not have a counterfactual analysis. While it is true that the policies implemented during the crisis have been calamitous, how certain can we be that Greece or Italy would have done better outside the euro zone? And can we say unhesitatingly that these countries would not have pursued free market policies anyway? Are we sure, in short, that Europe’s leaders would have all adopted pragmatic economic policies if the euro had not existed? Second, as the result of two years of Brexit negotiations shows, the process of disintegration is anything but a stroll in the park. A country’s departure from the euro zone would not be merely a Brexit, with the attendant uncertainties about commercial, financial and fiscal relations between a 27 member zone and a departing country, but rather a major shock to all the European Union members. It is difficult to imagine the exit of one or two euro zone countries without the complete breakup of the zone; we would then witness an intra-European trade war and a race for a competitive devaluation that would leave every country a loser, to the benefit of the rest of the world. The costs of this kind of economic disorganization and the multiplication of uncoordinated policies would also hamper the development of a socially and environmentally sustainable European policy, as the European Union is the only level commensurate with a credible and ambitious policy in this domain.

To say that abandoning the euro would be complicated and/or costly, is not, however, a solid argument in its favour. There is a stronger argument, one based on the rejection of the equation “euro = neoliberal policies”. Admittedly, the policies pursued so far all fall within a neoliberal doctrinal framework. And the institutions for the European Union’s economic governance are also of course designed to be consistent with this doctrinal framework. But the past does not constrain the present, nor the future. Even within the current institutional framework, different policies are possible, as shown by the (belated) activism of the ECB, as well as the exploitation of the flexibility of the Stability and Growth Pact. Moreover, institutions are not immutable. In 2012, six months sufficed to introduce a new fiscal treaty. It headed in the wrong direction, but its approval is proof that reform is possible. We have worked, and we are not alone, on two possible paths for reform, a dual mandate for the ECB, and a golden rule for public finances. But other possibilities could be mentioned, such as a European unemployment insurance, a European budget for managing the business cycle, or modification of the European fiscal rules. On this last point, the proposals are proliferating, including for a rule on expenditures by fourteen Franco-German economists, or the replacement of the 3% rule by a coordination mechanism between the euro zone members. Reasonable proposals are not lacking. What is lacking is the political will to implement them, as is shown by the slowness and low ambitions (especially about the euro zone budget) of the decisions taken at the euro zone summit on 14 December 2018.

The various reforms that we have just mentioned, and there are others, indicate that a change of course is possible. While some policymakers in Europe have shown stubborn persistence, almost tantamount to bad faith, we remain convinced that neither European integration nor the euro is inevitably linked to the policies pursued so far.

[1] This post is an updated and revised version of the article “Le maintien de l’euro n’est pas synonyme de politiques néolibérales” [Maintaining the euro is not synonymous with neoliberal policy], which appeared in Le Monde on 8 April 2017.