The ECB is extending its QE programme but mixes up its communications

By Paul Hubert

On Thursday, March 10, after the meeting of its Governing Council, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced a series of additional measures for the quantitative easing of monetary policy. The aim is to prevent the onset of deflation and to boost growth in the euro zone. The key innovation lies in the measure for bank financing at negative rates. While the measures were well received by the markets at the time of the announcement, a lapse in Mario Draghi’s communications during the press conference following the Board of Governors meeting greatly undercut some of the impact expected from the decisions taken.

What decisions were taken?

– The three key rates set by the ECB were lowered. The main refinancing rate went down from 0.05% to 0%, while the marginal lending rate was cut from 0.30% to 0.25%. Finally, the deposit facility rate, which compensates the excess reserves that banks hold on the ECB’s balance sheets, is down from -0.30% to -0.40%. It thus now costs a bank more to have cash on the ECB’s balance sheet.

– Quantitative easing (QE) has been extended in terms of its scale – securities purchases rose from €60 bn to €80 bn per month – but especially in terms of the types of securities eligible for purchase. While heretofore the ECB has bought government bonds (sovereign and/or local authority bonds), it will now buy high-quality corporate bonds, based on rating agency criteria. This measure is a direct response to the drying up of the supply of government securities and is expected to directly influence the conditions for corporations active on the bond markets.

– The most significant innovation concerns the new Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTRO), which are intended to reboot the channels of bank lending and to provide financing to banks on the condition that they finance the real economy. These loans to banks will be at a zero or even negative rate, based on various criteria, including the amount of loans that the banks provide to households and businesses. In other words, the ECB will pay banks meeting these criteria, so that they in turn lend.

What is the expected impact?

The effect to be expected from these measures depends on the situation of the credit market. Numerous studies show that in normal times these measures have a positive effect on the economy. However, this holds true only if it is the supply of credit that is currently constricted in the euro zone. Conversely, if the problem lies in the demand for credit on the part of consumers and businesses who have poor prospects in terms of income and profits, then these measures will have little effect. In granting banks such favourable conditions, it is easy to imagine that the ECB is betting on increasing the solvent demand for credit, that is to say, that the ECB is providing banks with strong incentives to lend to households and individuals that might have appeared non-creditworthy in previous conditions. Another expected effect of the lower deposit facility rates and the increase in QE will pass through the channel of a lower exchange rate for the euro, which will promote euro zone exports and increase imported inflation, and therefore overall inflation in the euro zone. This channel is potentially even more important given that the US Federal Reserve has initiated a period of monetary tightening.

Nevertheless, a more relevant economic policy would be to make use of fiscal policy to support demand, especially as the conditions for State financing are at historically low levels: the French state in 2016 is earning money from issuing debt of less than 4 years. Monetary policy would then have all the more effect.

Why announce that there’s no manoeuvring room left?

At the press conference following the meeting of the Governing Council, Mario Draghi announced that the ECB didn’t expect “to reduce rates further”, which had the effect of completely changing the financial markets’ interpretation of the decisions announced just before that. While the aim of these very expansionary decisions is to further ease monetary and financial conditions and to lower the exchange rate for the euro, the announcement that future changes in the ECB’s monetary policy could only be in a more restrictive direction transformed investor expectations.

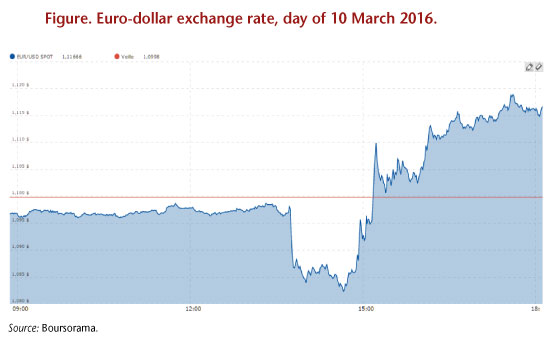

As one of the main channels for the transmission of monetary policy involves expectations, several studies conducted on data from the US [1], Britain [2] and the euro zone [3] show that a central bank’s communications need to be consistent with its decisions, otherwise the impact expected from monetary policy will be limited. This is called the “signal effect” of monetary policy. Mario Draghi’s short statement is one such example. The following graph shows the exchange rate of the euro vis-à-vis the dollar during the course of 10 March. The sharp drop at mid-day corresponds to the publication of the decisions taken by the Board of Governors, while the equally sharp rise corresponds to the contradictory message issued a few minutes later at the press conference. We thus see that as a series of highly expansionary measures – one of whose goals is to push down the euro – was announced, the euro eventually rose vis-à-vis the US dollar as if restricting measures had been put in place.

This does not necessarily mean that these decisions will have no effect, but that some of the effect will be lessened, or even disappear. Some transmission channels other than the signal effect remain operative. While the exchange rate channel has now been limited by the restrictive effect generated by the channel of expectations, we will see in the weeks and months to come whether capital movements induced by the decisions taken will have the effect expected on the euro exchange rate.

[1] Hubert, Paul (2015), “The Influence and Policy Signalling Role of FOMC Forecasts”, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 77(5), 655-680.

[2] Hubert, Paul, and Becky Maule (2016), “Policy and Macro Signals as Inputs to Inflation Expectation Formation”, Bank of England Staff Working Paper, No. 581.

[3] Hubert, Paul (2015), “ECB Projections as a Tool for Understanding Policy Decisions”, Journal of Forecasting, 34(7), 574-587, or Hubert, Paul (2016), “Disentangling Qualitative and Quantitative Central Bank Influence”, OFCE Working Paper, No. 2014-23.