By Christine Rifflart

The rise in public transport prices had barely been in force for two weeks when this lit the fire of revolt and led to a new twist in the so-called “Brazilian development model”. With its aspirations for high-quality public services (education, health, transport, etc.), the new middle class that formed during the last decade is claiming its rights and reminding the government that the money put up to host major sports events (2014 World Cup, 2016 Olympics) should not be spent to the detriment of other priorities, especially when growth has ceased and budget constraints demand savings.

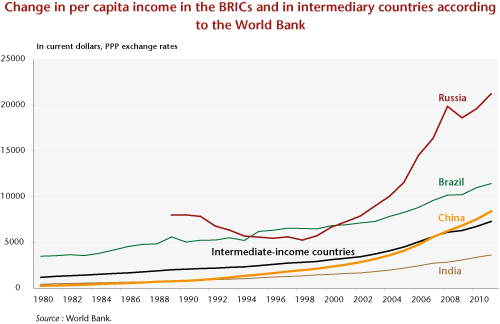

Over the years, Brazil’s growth accelerated from 2.5% per year in the 1980s and 1990s to almost 4% between 2001 and 2011. More importantly, for the first time the growth benefited a population that had traditionally been left out. Up to then, the slow growth of per capita income had gone hand in hand with rising inequality (the Gini coefficient for the period, at over 0.6, is one of the highest in the world) and an increase in poverty rates, which exceeded 40% during the 1980s. As hyperinflation was finally defeated by the 1994 “Plan Real”, growth resumed but remained fragile due to the series of external shocks that have hit the country (impact of the Asian crisis of 1997 and the Argentine crisis of 2001).

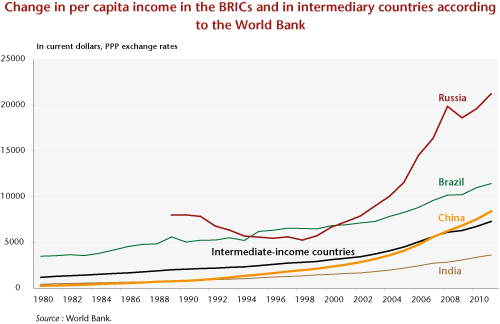

Lula’s accession to the presidency on 1 January 2003 marked a real turning point in this growth dynamic (Figure 1). While continuing the liberal orthodoxy of his predecessor F. H. Cardoso with respect to macro-economic policy and financial stability (unlike Argentina, for example), the new government took advantage of the renewed growth to better distribute the country’s wealth and to try to eradicate poverty. According to household surveys, real household income grew in local currency by 2.7% per year between 2001 and 2009, and the poverty rate fell by almost 15 percentage points to 21.4% of the population by the end of the period. In addition, the real income of the first eight deciles, especially the poorest 20% of the population, has increased much faster than the average income (Figure 2). Ultimately, 29 million Brazilians have joined the ranks of the new middle class, which now numbers 94.9 million (50.5% of the population), while the upper income class has welcomed 6.6 million additional Brazilians (and now represents 10.6% of the population). In contrast, the ranks of the poor decreased by 23 million, to 73.2 million in 2009. In terms of income, the new middle class now accounts for 46.2% of distributed income, more than the richest category, which saw its share decline to 44.1% [1].

This new configuration of Brazilian society is changing consumption patterns and aspirations, particularly in terms of education, access to health care, infrastructure, etc. But while consumer spending has accelerated for 10 years (durables in particular) and stimulated private investment, the wind of democratization is posing a serious challenge to the government. For while the hike in public transport prices was quickly canceled, providing new infrastructure and improving the quality of public services in a country that is 15 times the size of France is not done in a day. In 2012, of 144 countries surveyed, the World Economic Forum (pp 116-117) ranked Brazil 107th for the quality of its infrastructure and 116th for the quality of its education system. The authorities must skillfully respond to the legitimate demands of the population, especially the youth [2].

The country has a solid basis for dealing with this and stimulating investment: a stable political and macroeconomic environment, sound public finances, external debt below 15% of GDP, abundant foreign exchange reserves, the confidence of the financial markets and direct foreign investors, and of course varied and abundant natural resources in agriculture (soybeans, coffee, etc.), mining (iron ore, coal, zinc, bauxite, etc.) and energy (hydroelectricity, oil).

But many difficulties lie ahead. Currently, growth is lacking, and it is even running up against problems with production capacity. In 2012, growth came to only 0.9% (insufficient to increase per capita income) and, even though investment is recovering, the forecasts for 2013 have been regularly revised downwards to around 3%. At the same time, inflation is picking up, driven by strong pressure on the labour market (at 5.5%, the unemployment rate is very low), and since 2008 productivity has stagnated. Inflation, which hit 6.5% in May, is at the top of the range allowed by the monetary authorities. To meet the target of 4.5%, which would mean a reduction of more or less 2 percentage points, in April the central bank raised its key rate from 7.25% to 8%. Monetary policy is nevertheless still very accommodative – the difference between the interest rate and the inflation rate has never been so small – and the moderate growth should lead to calming the inflationary pressures. In addition, the relative support monetary policy is giving to the economy is being offset by a policy of continuing fiscal consolidation. Following a primary surplus of 2.4% of GDP in 2012, the goal for this year is to maintain this at 2.3%. The net public sector debt is continuing to decline: from 60% ten years ago to 43% in 2008, reaching 35% last April.

The virtual stagnation in growth has been due in particular to a serious problem with competitiveness, which undercut the country’s growth potential. In a lackluster international economy, higher production costs and a seemingly overvalued currency have resulted in a drop in export performance, a reluctance to invest, and greater recourse to imports. The current account balance deteriorated by 1 GDP point in one year, reaching 3% in April.

To deal with this supply-side problem, Brazil’s central bank is intervening more and more to counter the adverse effects of capital inflows – attracted by high interest rates – on the exchange rate, while the government is seeking to boost investment. The investment rate, which has been under 20% of GDP over the last 20 years and close to 15% between 1996 and 2006, is structurally insufficient to lead the economy back onto a path of virtuous growth. For comparison, the investment rate over the past five years has been 44% in China, 38% in India and 24% in Russia. To lift Brazil’s investment rate towards a target of around 23%-25%, in 2007 the government introduced a “growth acceleration programme” (PAC), based on the implementation of major infrastructure projects.

In four years, public investment rose from 1.6% of GDP to 3.3%. The year 2011 saw the launch of the second phase of the PAC, which is slated to receive a budget of 1% of GDP per year for 4 years. There are also other investment programmes whose benefits, though disappointing in 2012, should still help resolve some of the problems. But the efforts being made are still insufficient. According to a 2010 study by Morgan Stanley [3], Brazil would need to invest 6 to 8% of its GDP in infrastructure every year for 20 years to catch up with the level of the infrastructure in South Korea, and 4% to catch that of Chile, the benchmark in the field in South America!

By improving the productive supply and by stimulating demand through increased public investment, the authorities’ objective is therefore to make up some of the delay built up from the past. But is it possible to carry out large-scale investment projects while simultaneously pursuing a policy of debt reduction when net public debt is close to 35% of GDP? The authorities should speed up the reform process to spur private investment, in particular by promoting the development of a national long-term savings programme (pension reform, etc.) while stimulating financial intermediation, which goes hand in hand with this.

The volume of loans granted by the financial sector to the non-financial sector represented only 54.7% of GDP in May. A little less than half of these are earmarked loans (rural credit, National Development Bank, etc.) at heavily subsidized interest rates (0.5% in real terms against 12% for non-subsidized loans to business, and 0.2% against 27.7% respectively for individuals). But the state must also reform a cumbersome and corrupt government.

Brazil has been an emerging country for over four decades. With an income of 11,500 dollars (PPP) per capita, it is time that this great country reaches adulthood by providing developed country quality standards for its public services and by refocusing its new development model on its new middle class, whose needs are still going unmet.

[1]See The Agenda of the New Middle Class | Portal FGV on the site of the Fondation Gétulio Vargas.

[2]http://www.oecd.org/eco/outlook/48930900.pdf

[3]See the study by Morgan Stanley Paving the way, 2010.

Commentaires