Italy’s debt: Is the bark worse than the bite?

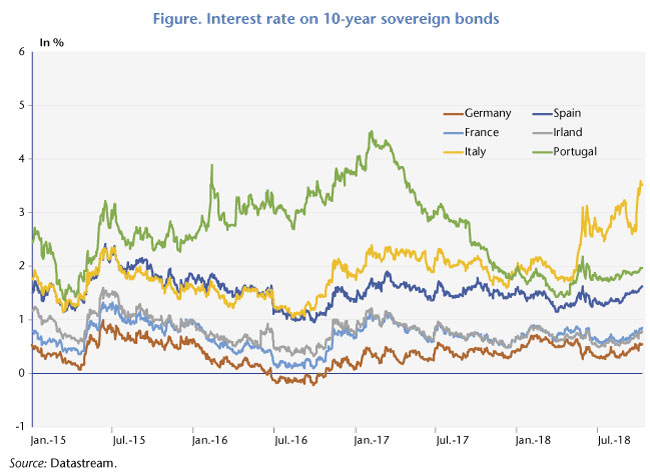

The spectre of a sovereign debt crisis in Italy is rattling the euro zone. Since Matteo Salvini and Luigi di Maio came to power, their headline-catching declarations on the budget have proliferated, demonstrating their desire to leave the European budgetary framework that advocates a return to an equilibrium based on precise rules[1]. Hence the announcement of a further deterioration in the budget when the update of the Economic and Financial Document was published at the end of September 2018 frayed nerves on the financial markets and triggered a further hike in bond rates. (graphic).

But should we really give in to panic? The crucial question is just how sustainable the Italian public debt really is. Looking up to 2020, the situation of the euro zone’s third-largest economy is less dramatic than it might appear. Stabilizing interest rates at the level of end September 2018 would leave the public debt largely sustainable. It will decline in 2019, from 131.2% to 130.3% of GDP. Given our assumptions[2], only a very sharp, long-lasting rise in bond interest rates in excess of 5.6 points would lead to an increase in the public debt ratio. In other words, the bond rate would have to exceed the level reached at the peak of the 2011 sovereign debt crisis. Should such a situation occur, it’s hard to believe that the ECB would not intervene to reassure the markets and avoid a contagion spreading through the euro area.

A very strong fiscal stimulus in 2019

A very strong fiscal stimulus in 2019

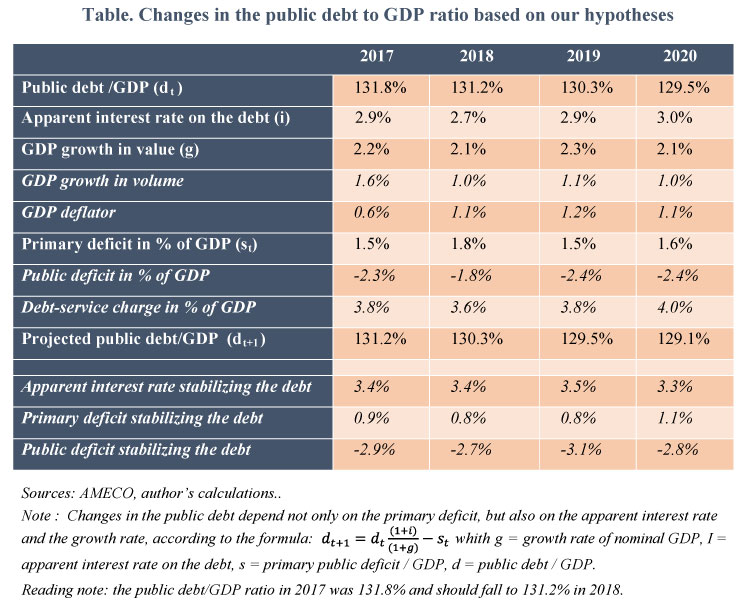

Changes in the public debt ratio depend heavily on the assumptions adopted. The ratio varies with the general government balance, the GDP growth rate, the deflator, and the apparent interest rate on the public debt (see calculation formula below).

In budgetary matters, despite their differing views, the two parties making up the Italian government (La Ligue and the 5 Star Movement) seem to agree on at least one point: the need to loosen budget constraints and boost demand. In any case the government contract, published in May 2018, was unequivocal. It announced a fiscal shock amounting to approximately 97 billion euros over 5 years, or 5.6% of GDP over the five-year period. But although the measures have been gradually reduced, the draft presented to the Italian Parliament plans for a public deficit of 2.4% of GDP for 2019, far from the original target of 0.8% set in the Stability and Growth Pact forwarded to the European Commission on 26 April 2018. We assume that the 2019 budget will be adopted by the Parliament, and that the deficit will indeed be 2.4% of GDP. We therefore anticipate a positive fiscal impulse of 0.7 GDP point in 2019. This stimulus breaks down as follows:

– A decrease in compulsory taxation of 5 billion, or 0.3 GDP point, linked to the gradual introduction of the “flat tax” of 15% for SMEs, a measure supported by the League. The extension of the flat tax to all businesses and households was postponed until later in the mandate, without further clarification;

– An increase in public spending, calculated roughly at 7 billion euros, or 0.4 GDP point. Let’s first mention the flagship measure of the 5 Stars Movement, the introduction of a citizens’ pension (in January 2019) and a citizens’ income (in April 2019), for an estimated total amount of 10 billion euros. The citizens’ pension will supplement the pension of all pensioners, bringing it to 780 euros per month. For the working population, the principle is similar – supplementing the salary up to 780 euros – but subject to conditions: recipients will have to take part in training and accept at least one of the first three job offers that are presented to them by the Job Centre. The revision of the pension reform, which provides for the “rule of 100”, will also allow retirement when the sum between a person’s age and the years worked reaches 100, in certain conditions. This should cost 7 billion euros in 2019. Finally, an investment fund of 50 billion euros is planned over 5 years; we are expecting an increase in public investment of 4 billion euros in 2019. To finance the spending increase without pushing the public deficit above 2.4%, the government will have to save 14 billion euros, equivalent to 0.8 GDP point. For the moment, these measures are very imprecise (further rationalization of spending and tax amnesty measures).

For 2020, the Italian government has declared that the public deficit will fall to 2.1% of GDP. However, to arrive at this figure, given our growth assumptions, would require tightening up fiscal policy somewhat, which is not very credible. We therefore assume a quasi-neutral fiscal policy in 2020, which means that the deficit would remain at 2.4% of GDP.

With a very positive fiscal stimulus in 2019, annual growth (1.1%) should be higher than in 2018. This acceleration is more visible year-on-year: growth in Q4 of 2019 will be 1.6%, compared with 0.6% in Q4 of 2018. Although low, this level is nevertheless higher than the potential growth rate (0.3%) in 2019 and 2020. The output gap is in fact still large and leads to 0.4 GDP point of catch-up per year. Spontaneous growth[3] thus amounts to 0.7 GDP point in 2019 and 2020. In addition, we anticipate a much stronger fiscal impulse in 2019 (0.7 GDP point) than in 2020 (0.1 GDP point). Other shocks, such as oil prices or price competitiveness, will be more positive or less negative in 2020 than in 2019.

Changes in the public debt ratio also depend on developments in the GDP deflator. However, prices should remain stable in 2019 and 2020, due in particular to wage moderation. Thus, nominal growth should be around 2% in 2019 and 2020.

Finally, we assume that the interest rate on the debt will stay at the level of the beginning of October 2018. Given the maturity of the public debt (seven years), the rise in rates forecast for 2019 and 2020 will be very gradual.

Reducing the public debt up to 2020

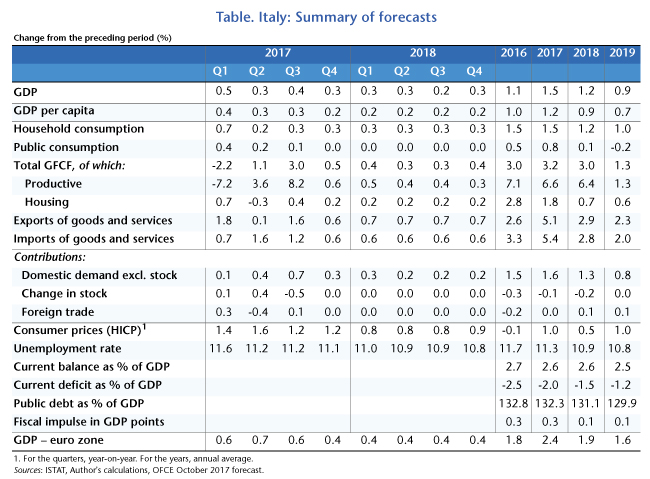

Under these assumptions, the public debt should decline continuously until 2020, falling from 131.2% of GDP in 2018 to 130.3% in 2019 and then to 129.5% in 2020 (table). In light of our assumptions, the public debt will fall in 2019 if the apparent interest rate remains below 3.5% of GDP, i.e. if the debt-service charge relative to GDP is less than 4.5%.

However, for the apparent interest rate to rise from 2.7% in 2018 to 3.5% in 2019, given the 7-year maturity on the debt, the interest rate charged by markets would have to rise by about 5.6 points on average over the year, for one year. While this scenario cannot be excluded, it seems certain that the ECB would intervene to allow Italy to refinance at lower cost and avoid contagion.

Still, even if interest rates do not reach this level, any additional rise in interest rates will further limit the Italian government’s fiscal manoeuvring room, or it will lead to a larger-than-expected deficit. Also, the deficit forecast by the government is based on an optimistic assumption for GDP growth of 1.5% in 2019; if growth is weaker, the deficit could widen further, unsettling nerves on the market and among investors and jeopardizing the sustainability of the debt.

[1] L. Clément-Wilz (2014), “Les mesures ‘anti-crise’ et la transformation des compétences de l’Union en matière économique” [“’Anti-crisis’ measures and the transformation of the competences of the EU in economic matters”], Revue de l’OFCE, 103.

[2] For more information, see the forthcoming 2018-2020 forecast for the global economy, Revue de l’OFCE, (October 2018).

[3] Spontaneous growth for a given year is defined as the sum of potential growth and the closing of the output gap.

In 2017, it was domestic demand that was driving growth; the contribution of foreign trade was zero because of the dynamism of imports and the absence of any improvement in price competitiveness. We anticipate that the contribution of foreign trade will be null in 2018 and slightly positive in 2019 thanks to an improvement in competitiveness (Table).

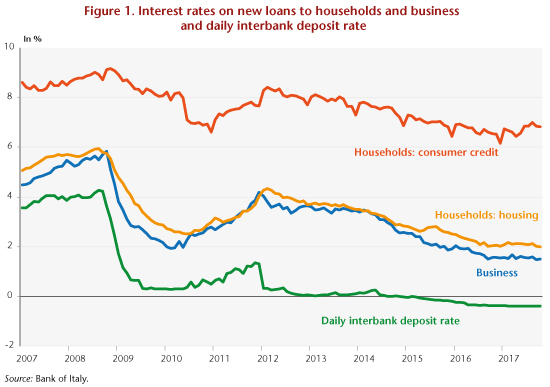

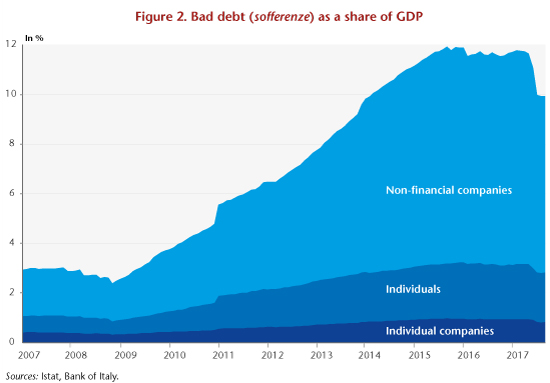

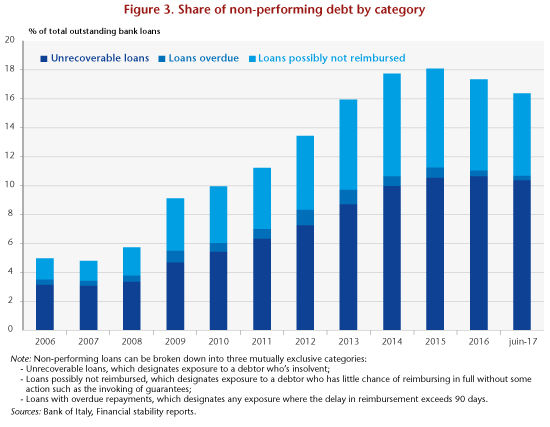

In 2017, it was domestic demand that was driving growth; the contribution of foreign trade was zero because of the dynamism of imports and the absence of any improvement in price competitiveness. We anticipate that the contribution of foreign trade will be null in 2018 and slightly positive in 2019 thanks to an improvement in competitiveness (Table). The Italian government has implemented various reforms to cope with the difficulties facing the country’s banking sector. First, it has been working to accelerate the clearance of bad debts and to reform the law on bankruptcy. Legislative Decree 119/2016 introduced the “martial pact” (patto marciano), which makes it possible to transfer real estate used as collateral to creditors (other than the debtor’s principal residence); the real estate can then be sold by the creditor if the default lasts more than 6 months. Other rules aim at speeding up procedures: the use of digital technologies for hearings of the parties, the establishment of a digital register of ongoing bankruptcy proceedings, the reduction of opposition periods during procedures, an obligation for judges to order provisional payments for amounts not in dispute, the simplification of the transfer of ownership, etc.

The Italian government has implemented various reforms to cope with the difficulties facing the country’s banking sector. First, it has been working to accelerate the clearance of bad debts and to reform the law on bankruptcy. Legislative Decree 119/2016 introduced the “martial pact” (patto marciano), which makes it possible to transfer real estate used as collateral to creditors (other than the debtor’s principal residence); the real estate can then be sold by the creditor if the default lasts more than 6 months. Other rules aim at speeding up procedures: the use of digital technologies for hearings of the parties, the establishment of a digital register of ongoing bankruptcy proceedings, the reduction of opposition periods during procedures, an obligation for judges to order provisional payments for amounts not in dispute, the simplification of the transfer of ownership, etc.