By Odile Chagny (IRES) and Sabine Le Bayon

A year and a half after introducing a statutory minimum wage, the German Commission in charge of adjusting it every two years decided on 28 June to raise it by 4%. On 1 January 2017, the minimum will thus rise from 8.50 to 8.84 euros per hour. This note offers an initial assessment of the implementation of the minimum wage in Germany. We point out that the minimum wage has had some of the positive effects that were expected, helping to reduce wage disparities between the old Länder (former West Germany) and the new Länder (former East Germany), and between more skilled and less skilled workers. By establishing recognition of the wage value of Germany’s “mini-jobs”, the minimum wage has made these marginal forms of employment less attractive for employers, representing a major rupture for the welfare state. But the minimum wage has also had some less fortunate results. Due probably to the flattening of pay scales at the minimum wage level, certain categories of employees in former West Germany seem to have suffered from the wage restraint that was imposed on them just before the introduction of the minimum wage, as companies limited the impact of the minimum wage on their total salary costs.

Unlike in France, there are no rules requiring an automatic annual revision of the minimum wage in Germany. It is adjusted only every two years upon a decision by the Commission. The decision taken on 28 June 2016 will take effect on 1 January 2017. There will then not be another revision until 2019, based on a decision taken in June 2018.

At first glance, the revaluation is fairly significant (+4% on 1 January 2017, i.e. a 2% annual rate) when compared to recent revisions of the minimum wage in France, where the SMIC, as it is called, rose by 1% per year over the last four years. This is due to the fact that, in accordance with the law establishing the minimum wage, the revaluation that takes place in Germany is made in light of increases concluded under collective bargaining agreements[1], thereby ensuring equivalent gains in purchasing power for all employees covered by a collective agreement. Since increases in negotiated wages have been relatively high since 2012 (+2.7% annual rate for the basic hourly wage index negotiated between 2011 and 2015, against +1.6% for the basic monthly wage in France over this same period), this automatically affects the minimum wage[2].

However, the level of the minimum wage is low and it is likely to remain so. It is much lower than the current level in France (9.67 euros since January 2016). According to the national accounts, this represented 34% of the average wage in 2015 (47% in France) and 48% of the median wage of full-time employees in 2014 (61% in France), which puts Germany in the lower range among the major European economies[3].

Nevertheless, even though set at a relatively low level, much was expected of the minimum wage’s ability to correct the very sharp wage segmentation in Germany[4], which points to the need to pay particular attention to the categories of employees who benefited from it.

Between 4 and 5.8 million employees were potentially affected by the introduction of the minimum wage in 2015

Somewhat paradoxically, it is difficult to get a clear picture of the actual number of employees who received less than 8.50 euros at the time the minimum wage was introduced. The most recent estimates vary between 4 million according to Destatis and a range of 4.8 to 5.4 million according to the WSI Institute (between 10% and 16% of the total workforce)[5]. This is because the law establishing the minimum wage left some uncertainty about its practical application. For instance, the law stipulates that the minimum wage of 8.5 euros per hour applies while taking into account the actual working time (knowing that there is no statutory work week in Germany), and it gives no precise definition of the pay elements to be taken into account (year-end bonuses, 13th month bonus, miscellaneous bonuses). On this point, following an employee’s complaint, on 25 May 2016 Germany’s Federal Labour Court ruled that a bonus previously paid once a year can be included in the calculation of the minimum wage when it is henceforth paid fractionally each month and this has been approved by a company agreement. This automatically leads to decreasing the number of potential beneficiaries.

While calculating the number of people receiving less than 8.50 euros is tricky, there is nevertheless relatively good agreement on estimates indicating that employees holding mini-jobs and employees in the new Länder just prior to the introduction of the minimum wage were the main ones affected. Thus, according to Destatis, 55% of the employees concerned were “mini-jobbers”, mainly in western Germany where they are the most numerous. In eastern Germany, the proportion of people earning less than 8.50 euros was twice as high as in western Germany (just over 20% of employees, around 10% in the old Länder). Not surprisingly, more than 80% of those working for less than 8.50 euros were in companies not covered by collective bargaining agreements, with twice as many women as men. Finally, catering and retail were the trades most affected, as approximately 50% and 30% of their employees earned less than 8.50 euros, according to the WSI in 2014.

1.9 million people were on the minimum wage in April 2015 according to Destatis

The minimum wage has partly fulfilled its mission by ensuring a “decent” wage for society’s most vulnerable people. If we stick to the Destatis estimate, while 4 million people received a wage of less than 8.50 euros in April 2014, “only” 1 million were in this situation a year later. Moreover, among the 1.9 million employees earning 8.5 euros in April 2015, the great majority of whom were undoubtedly earning less before the entry into force of the minimum wage, 91% worked in companies not covered by a collective agreement and 56% held mini-jobs.

A significant increase in wages in the new Länder and for mini-jobs

It is obviously too early to have microeconomic surveys with accurate information about changes in the salaries of those affected by the introduction of the minimum wage, so the main source used is the quarterly wage survey [6], which provides data on different job categories (conventional jobs, i.e. subject to social security contributions, and mini-jobs) and skills levels.

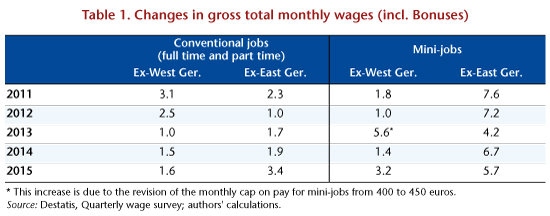

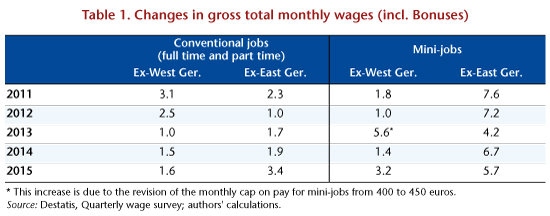

Based on this survey, it is clear that the implementation of the minimum wage undoubtedly led to raising the monthly wages of certain categories of employees in 2015: for conventional jobs [7] in the new Länder and for mini-jobs in western Germany (Table 1).

Hourly wages in eastern Germany rose especially quickly in 2015 for unskilled (+8.6%) and semi-skilled employees (+5.8%) compared to those with average qualifications (+4%), helping to reduce wage inequality in these German states. However, no such trend could be seen in western Germany regardless of the skills level.

Questioning the logic of mini-jobs

Given that 60% of employees holding mini-jobs received less than 8.5 euros per hour in 2014, one would expect a more marked acceleration of average earnings in this category of employees. The most likely reason why this was not the case is that the implementation of the minimum wage has de facto made these jobs less attractive for employers and led to a reduction in those workforce numbers and probably in the hours worked.

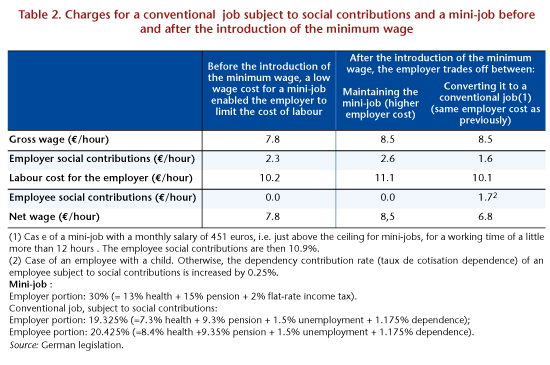

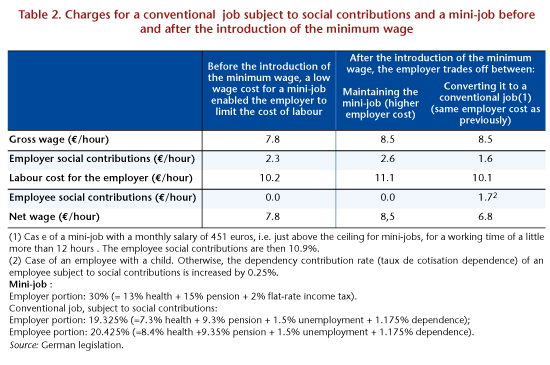

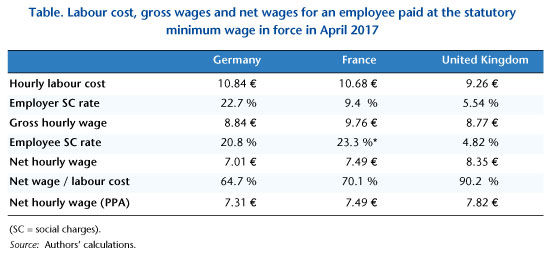

While mini-jobs are characterized by an absence of employee social security contributions and the acquisition of fewer employee rights, they are nonetheless subject to higher levies paid by employers (mainly social contributions and flat-rate tax on income) than in the case of a conventional job. As a result, the attraction for employers prior to the introduction of the minimum wage was due mainly to the flexibility offered by this type of employment as well as to the possibility of low hourly wages[8], as there was no limitation on working hours (the only constraint being the monthly ceiling of 450 euros).

However, by including mini-jobs within the coverage of the minimum wage, the law has made them much less financially attractive to employers because their hourly cost now exceeds that of a conventional job, including a midi-job[9] (see Table 2), with the number of hours implicitly capped (at 12 hours per week given the monthly ceiling of 450 euros).[10]

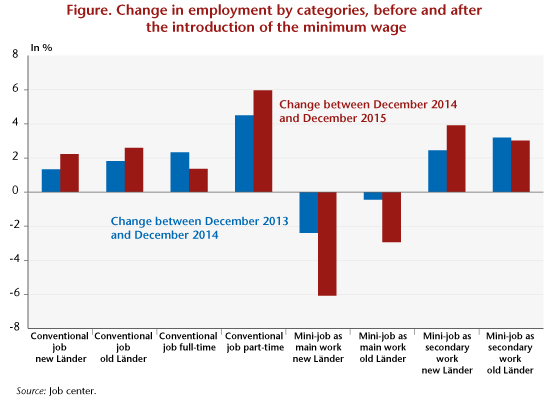

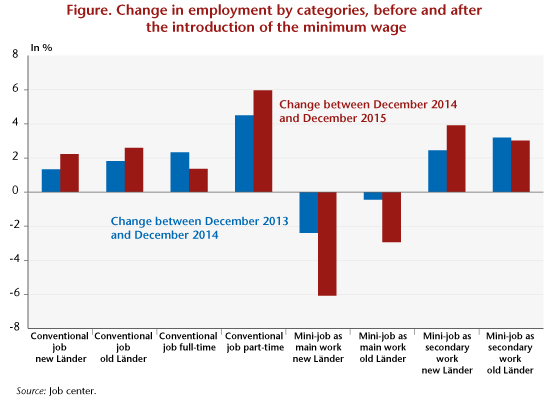

We therefore expect a reduction in the number of these jobs through simple destruction or reclassification as conventional jobs [11]. There has in fact been a sharp decrease in the number of mini-jobs since the beginning of 2015, especially mini-jobs that are the worker’s main activity, and an acceleration in the creation of conventional part-time jobs (graphic). The conversion into conventional jobs seems clear in the hotel, catering and retail trades, where mini-jobs had been prevalent and where conventional job creation has been particularly important. But although the conversion of mini-jobs into conventional jobs has been relatively high, it has not been massive, which is probably due both to a reduction in the actual hours worked so as to stay under the ceiling for mini-jobs (which for the employee has reduced the impact of a higher hourly wage) and to incorrect documentation of working time by the employer, with an underestimation of the hours worked[12]. The assurance that the legal conditions governing these jobs will be applied is even less certain given that the employee too may have a financial interest in non-compliance with the minimum wage, by accepting an underestimation of the number of hours so that their monthly wage remains below the 450 euro ceiling. The employee thus receives a net wage equal to the gross wage, which is not the case if the wage exceeds 450 euros and he occupies a midi-job, since the rate of the employee social contribution is then progressive and he becomes subject to conventional taxation (which depends on the employee’s family characteristics).

In the spring of 2015, 1 million people were still being paid below the minimum wage

The magnitude of the workforce still earning less than 8.5 euros after the implementation of the minimum wage raises several questions. This could of course be explained by the implementation deadlines and by the fact that various exemptions are allowed (long-term unemployed for the first 6 months of employment, employees in sectors providing for a transitional adaptation period – newspaper delivery, temping, the meat industry, hairdressing, agriculture, textile, laundry).

But we could also consider the actual capacity to implement the minimum wage in the “grey areas” of the collective bargaining system[13]. Among these 1 million workers, almost 80% were employed in companies not covered by collective agreements and 47% held mini-jobs.

This highlights the importance of official controls to ensure compliance, especially as the methods of calculating the hourly wage as defined by law and jurisprudence are problematic[14]. Parliament has provided for a requirement to report working hours, but this does not apply to all employees. Of course, for all mini-jobs and for those below a certain salary threshold[15] in certain sectors particularly affected by illegal work (construction, catering, passenger transport, logistics, industrial cleaning, meat industry, etc.), the employer is now required to record the start and end of each work day and the duration of work and keep these documents for two years to avoid circumvention of the law through unpaid overtime. But there are not many inspections, and the frequency even fell by about one-third in 2015 from 2014, even as the number of people affected by the minimum wage exploded.

A fairly moderate impact on the average wage of conventional jobs

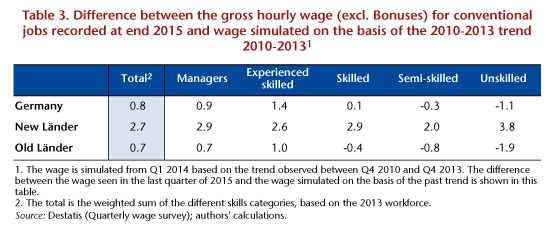

More unexpectedly, it seems that some companies anticipated the coming into force of the minimum wage by slowing increases in unskilled wages in the months preceding the law’s implementation (recall that parliamentary elections took place in October 2013, and the minimum wage took effect in January 2015). The year 2014 was indeed characterized by a sharp halt to wage hikes for less skilled workers, which occurred in both the old and new Länder, a phenomenon that cannot be explained by objective factors related to the economic situation. This means, surprisingly, that certain categories of employees would have received higher wage increases in the absence of the introduction of the minimum wage.

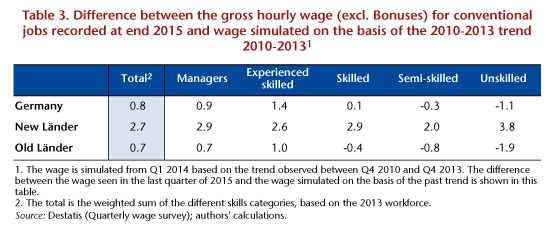

To assess this, we simulated the hourly wages in 2014 and 2015 for conventional jobs on the basis of the 2010-2013 trend (i.e. before the minimum wage was officially incorporated into the coalition agreement of autumn 2013), and we compared the wage observed at end 2015 with the one simulated by type of qualifications and Länder in order to see which employees were overall losers or winners (Table 3).

While in the new Länder on average all

categories of employees benefited from the implementation of the minimum wage, with a diffusion effect from the minimum wage on wages immediately above 8.50 euros (and a revaluation of all salary scales), it seems that in the old Länder the least skilled categories suffered from its introduction. In other words, those whose salary was slightly higher than the minimum wage before the law took effect would have enjoyed a higher hourly wage in early 2016 on the basis of past trends!

This braking effect is such that at the level of Germany as a whole, and given the weight of the old Länder in the workforce (81% of conventional waged jobs), the unskilled and semi-skilled have therefore generally suffered from the introduction of the minimum wage, a situation that is somewhat paradoxical and which most observers have failed to highlight, focusing instead on the analysis of developments following the minimum wage’s introduction.

If the stated objective of the law introducing a minimum wage in Germany was indeed achieved, namely, to end a situation where a significant number of employees were on extremely low wages, there are 1 million people who have yet to benefit, i.e. a quarter of the workforce who were potentially concerned. There is also evidence that many companies anticipated the introduction of the minimum wage in the year before its introduction by making trade-offs in their wage policy in order to limit the impact on their costs. The result is that not all employees have been winners from the introduction of the minimum wage. What has taken place in Germany, especially in the old Länder, is a form of redistribution among unskilled workers between those who have benefited from the law [16] and those earning a little more than the minimum wage, who have experienced two years of wage restraint.

[1] For this initial reassessment, the Commission based itself on changes in the negotiated hourly wages (excluding bonuses) between December 2014 and June 2016, which was 4%, including the retroactive effect of the latest collective agreement signed for the civil service.

[2] Like employee purchasing power, inflation rates in France and Germany have been very similar over the same period: +1.1% annual rate over the period 2011-2015 in Germany, 0.9% in France for the HICP.

[3] M. Amlinger, R. Bispinck and T. Schulten, 2016 : “The German Minimum Wage: experiences and perspectives after one year”, WSI Report No. 28e, 1/2016.

[4] O. Chagny and F. Lainé 2015: “Comment se comparent les salaires entre la France et l’Allemagne?”, Note d’analyse no. 33, France Stratégie.

[5] By removing the exceptions: trainees, apprentices and those under age 18.

[6] This was conducted among about 40,000 companies with more than 10 employees (5 in some sectors such as retail or catering to reflect the specific characteristics of these areas) in industry and the service sector.

[7] This observation holds whether one is interested in the total monthly pay (including bonuses) or the hourly wage excluding bonuses, with wage increases of respectively 3.4% and 4% in 2015.

[8] B. Lestrade, 2013: “Mini-jobs en Allemagne. Une forme de travail à temps partiel très répandue mais contestée”, Revue française des affaires sociales, 2013/4.

[9] For these contracts, which pay between 450 and 850 euros, the contribution rate for the employer is that of a conventional job, while the contribution rate for employees is progressive, ranging from 10.9% to 20.425% based on the salary.

[10] Note that the average working time in 2008 for these jobs was 12.8 hours per week (D. Voss and C. Weinkopf, 2012, “Niedriglohnfalle Minijob”, WSI Mitteilungen 1/2012).

[11] For a midi-job, if the employee works between 12 and 23 hours weekly, and in a conventional job more than 23 hours.

[12] The most common strategies for circumventing the law in terms of working time are: unpaid overtime, payment for a task without fixed working hours and poor calculation of the time worked (on-call time, etc.). For more, see T. Schulten, 2014, “Umsetzung und Kontrolle von Mindestlöhnen”, Arbeitspapiere 49, GIB, November 2014.

[13] For more, see: “Allemagne. L’introduction d’un salaire minimum légal : genèse et portée d’une rupture majeure”, O. Chagny and S. Le Bayon, Chronique internationale de l’IRES, no. 146, June 2014.

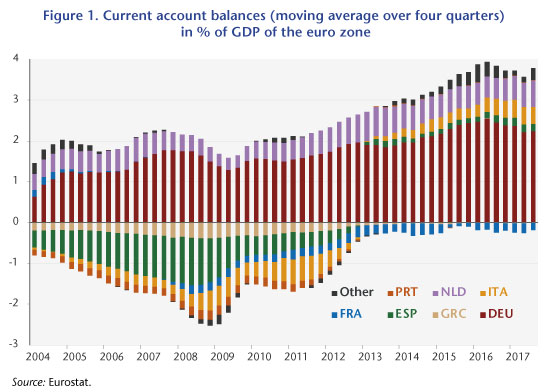

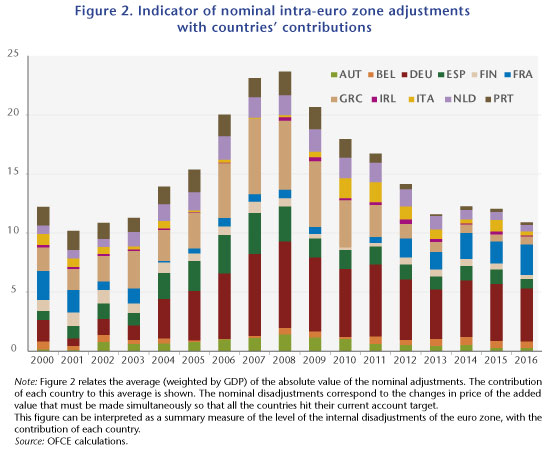

The trend towards diverging current account balances slowed sharply after 2009, and external deficits disappeared in almost all the euro zone countries. Despite this, there is still a significant gap between the northern and southern countries, so there cannot yet be any talk about reconvergence. Moreover, the fact that the deficits have fallen (Italian and Spanish) but not the surpluses (German and Dutch) has radically changed the ratio of the euro zone to the rest of the world: while the zone’s current account was close to balanced between 2001 and 2008, a significant surplus has formed since 2010, reaching 3.3% of GDP in 2016. In other words, the imbalance that was internal to the euro zone has shifted into an external imbalance between the euro zone and the rest of the world, in particular the United States and the United Kingdom. This imbalance is feeding Donald Trump’s protectionism and putting pressure on exchange rates. While the nominal exchange rate internal to the euro zone is not an adjustment variable, the exchange rate between the euro and the dollar can adjust.

The trend towards diverging current account balances slowed sharply after 2009, and external deficits disappeared in almost all the euro zone countries. Despite this, there is still a significant gap between the northern and southern countries, so there cannot yet be any talk about reconvergence. Moreover, the fact that the deficits have fallen (Italian and Spanish) but not the surpluses (German and Dutch) has radically changed the ratio of the euro zone to the rest of the world: while the zone’s current account was close to balanced between 2001 and 2008, a significant surplus has formed since 2010, reaching 3.3% of GDP in 2016. In other words, the imbalance that was internal to the euro zone has shifted into an external imbalance between the euro zone and the rest of the world, in particular the United States and the United Kingdom. This imbalance is feeding Donald Trump’s protectionism and putting pressure on exchange rates. While the nominal exchange rate internal to the euro zone is not an adjustment variable, the exchange rate between the euro and the dollar can adjust. In the current situation, claims by some euro zone countries are not accumulating on others in the zone, but there is accumulation by some euro zone countries on other countries around the world. This time the exchange rate (actual, weighted by accumulated gross assets) can serve as an adjustment variable. The appreciation of the euro would therefore reduce the euro zone’s current account surplus and depreciate the value of assets, which are probably accumulated in foreign currency. France however now appears as the last country in the euro zone running a significant deficit. Relative to the zone’s other countries, it is France that is contributing most (negatively) to the imbalances with Germany (positively). If the euro appreciates, it is likely that France’s situation would further deteriorate and that we would see a situation where the net internal position accumulates, but this time between France (on the debtor side) and Germany (creditor). This would not be comparable to the situation prior to 2012, since France is a bigger country than Greece or Portugal, and therefore the question of sustainability would be posed in very different terms. On the other hand, reabsorbing this imbalance by an adjustment of prices would require an order of magnitude such that, given the relative price differentials that would likely be needed between France and Germany, it would take several decades to achieve. It is also striking that, all things considered, since 2012, when France undertook a costly reduction in wages through the CICE tax credit and the Responsibility Pact, and Germany introduced a minimum wage and has been experiencing more wage growth in a labour market that is close to full employment, the relative imbalance between France and Germany, expressed in the adjustment of relative prices, has not budged.

In the current situation, claims by some euro zone countries are not accumulating on others in the zone, but there is accumulation by some euro zone countries on other countries around the world. This time the exchange rate (actual, weighted by accumulated gross assets) can serve as an adjustment variable. The appreciation of the euro would therefore reduce the euro zone’s current account surplus and depreciate the value of assets, which are probably accumulated in foreign currency. France however now appears as the last country in the euro zone running a significant deficit. Relative to the zone’s other countries, it is France that is contributing most (negatively) to the imbalances with Germany (positively). If the euro appreciates, it is likely that France’s situation would further deteriorate and that we would see a situation where the net internal position accumulates, but this time between France (on the debtor side) and Germany (creditor). This would not be comparable to the situation prior to 2012, since France is a bigger country than Greece or Portugal, and therefore the question of sustainability would be posed in very different terms. On the other hand, reabsorbing this imbalance by an adjustment of prices would require an order of magnitude such that, given the relative price differentials that would likely be needed between France and Germany, it would take several decades to achieve. It is also striking that, all things considered, since 2012, when France undertook a costly reduction in wages through the CICE tax credit and the Responsibility Pact, and Germany introduced a minimum wage and has been experiencing more wage growth in a labour market that is close to full employment, the relative imbalance between France and Germany, expressed in the adjustment of relative prices, has not budged.

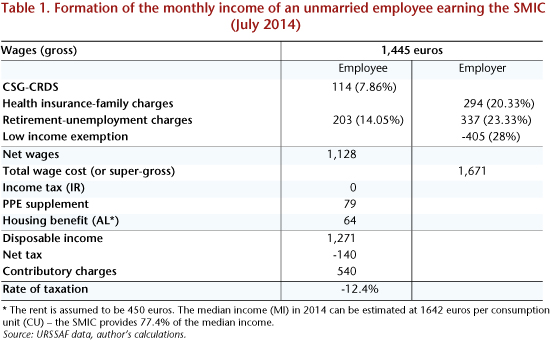

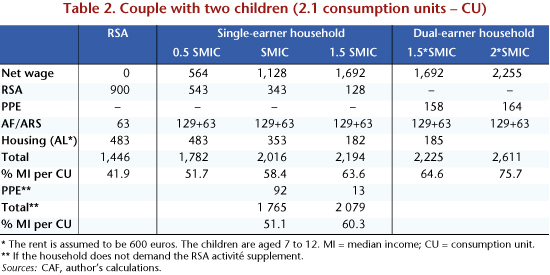

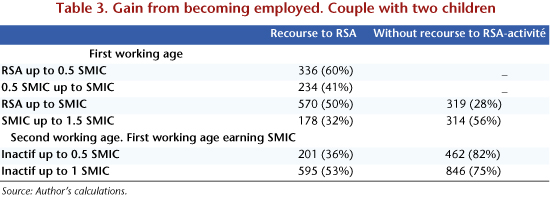

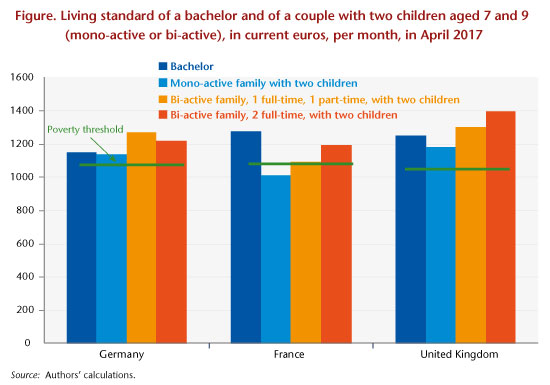

From the point of view of the relative position of minimum wage earners in relation to the general population, our study highlights the rather favourable situation of the United Kingdom. The living standard there is comparatively high: all the families considered in our typical cases have a standard of living above the poverty line, on the order of 30% higher for a family where both parents work full-time at the minimum wage. The gain from taking up a job is, as in France, high, while it is low in Germany in all the configurations.

From the point of view of the relative position of minimum wage earners in relation to the general population, our study highlights the rather favourable situation of the United Kingdom. The living standard there is comparatively high: all the families considered in our typical cases have a standard of living above the poverty line, on the order of 30% higher for a family where both parents work full-time at the minimum wage. The gain from taking up a job is, as in France, high, while it is low in Germany in all the configurations.